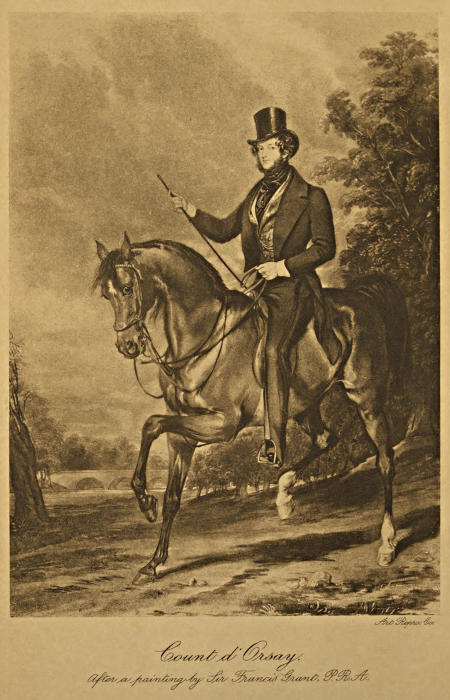

Whilst the Duke of Wellington approved of elegance and was himself known as “the Beau,” he felt obliged to advise his splendidly uniformed Grenadier Guards that their behavior was “not only ridiculous but unmilitary” when they rode into battle on a rainy day with their umbrellas raised. A dandy Wellington was not. Odd, then, that the picture of himself that Wellington liked most was done by one of the greatest dandies of his day – Count d’Orsay. d’Orsay painted the Duke in profile (above), in evening dress, and the Duke is said to have rather liked the picture, because it “made him look like a gentleman.”

Count Albert Guillaume d’Orsay, the son of one of Napoleon’s generals, and descended by a morganatic marriage from the King of Wurttemburg, was himself a gentleman in every sense, and his courtesy was of the highest kind. At the balls given by his regiment, although he was more courted than any other officer, d’Orsay always sought out the plainest girls and showed them the most flattering attentions. During his first visit to London, Count d’Orsay was invited once or twice to receptions given by the Earl and Countess of Blessington, where he was well received. Before the story proceeds any further it is necessary to give an account of the Earl and of Lady Blessington, since both of their careers had been, to say the least, unusual.

Lord Blessington was an Irish peer for whom an ancient title had been revived. He was remotely descended from the Stuarts of Scotland, and therefore had royal blood to boast of. He had been well educated, and in many ways was a man of pleasing manner. On the other hand, he had early inherited a very large property which yielded him an income of about thirty thousand pounds a year. He had estates in Ireland, and he owned nearly the whole of a fashionable street in London, along with the buildings erected upon it. Thrown together by the same society and so often in each other’s company, the Earl of Blessington became as devoted to D’Orsay as did his wife. The two urged the Count to secure a leave of absence and to accompany them to Italy. This he was easily persuaded to do; and the three passed weeks and months of a languorous and alluring intercourse among the lakes and the seductive influence of romantic Italy. Just what passed between Count d’Orsay and Marguerite Blessington at this time cannot be known, for the secret of it has perished with them; but it is certain that before very long they came to know that each was indispensable to the other.The situation was complicated by the Earl of Blessington, who, entirely unsuspicious, proposed that the Count should marry Lady Harriet Gardiner, his eldest legitimate daughter by his first wife. He pressed the match upon the embarrassed d’Orsay, and offered to settle the sum of forty thousand pounds upon the bride. The girl was less than fifteen years of age. She had no gifts either of beauty or of intelligence; and, in addition, d’Orsay was now deeply in love with her stepmother.

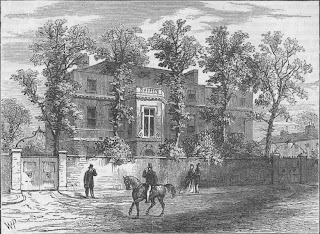

But once again I digress. Suffice it to say that eventually Lady Blessington and the Count set up a home together, both in London, at Gore House, and in Paris, where Lady Blessington died. Upon her death, and before when they found themselves in straightened financial waters, the Count drew upon his artistic talents, both in painting and sculpture, in order to earn money. Whatever one thought about the Count personally, no one could deny his artistic talent. d’Orsay would go on to produce a painting of Gore House, of which I can find no image to use here. Instead, I give you a contemporary print of Gore House –

And the description of d’Orsay’s painting, which illustrates the illustrious circles d’Orsay found himself within and also brings us back to the Duke of Wellington –

“A garden view of Gore House, the residence of the late Countess of Blessington, with Portraits of the Duke of Wellington, Lady Blessington, the Earl of Chesterfield, Sir Edwin Landseer, Count d’Orsay, the Marquis of Douro (2nd Duke of Wellington), Lord Brougham, the Misses Power, etc. In the foreground, to the right, are the Duke of Wellington and the Countess of Blessington; in the centre, Sir Edwin Landseer seated, who is in the act of sketching a very fine cow, which is standing in front, with a calf by its side, while Count d’Orsay, with two favorite dogs, is seen on the right of the group, and the Earl of Chesterfield on the left; nearer the house, the two Misses Power (nieces of Lady Blessington) are reading a letter, a gentleman walking behind. Further to the left appear Lord Brougham, the Marquis of Douro, etc., seated under a tree in conversation.”