Louisa Cornell

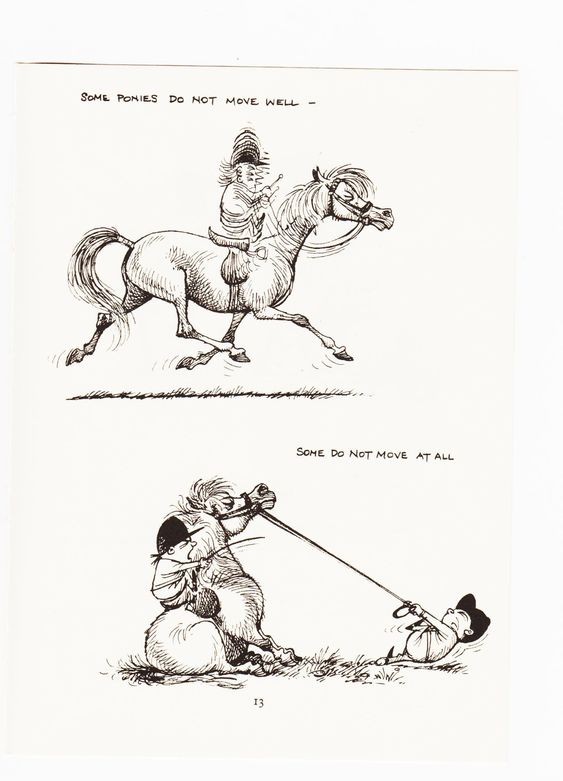

I spent the three best years of my childhood in a little village in Suffolk – Kelsale – where I learned to ride and, more important, how not to ride. One of my prized possessions from those years is a little book of young rider themed cartoons entitled Angels on Horseback by the English cartoonist, Norman Thelwell.

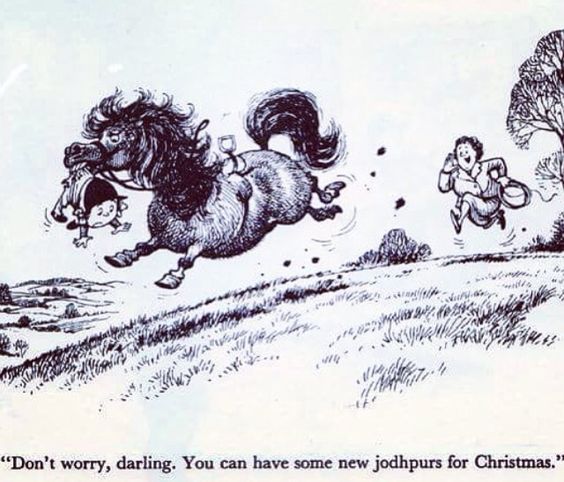

His work pokes fun in a harmless and hilarious way at the efforts of young equestrians to meet the expectations of their pushy horsey parents and their tyrannical riding instructors.

There is an entire series of books of Thelwell’s horsey themed cartoons. Fifty years later I still find them amusing and, in many cases, far too accurate for comfort when it comes to my own early riding adventures.

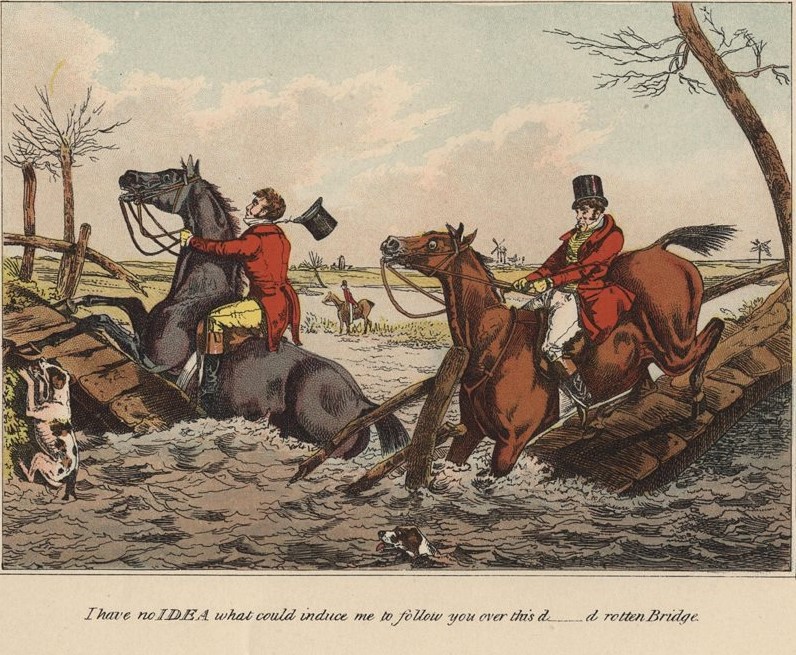

Perhaps that is why I am such a fan of the work of Regency era artist and caricaturist, Henry Alken (1785-1851.) The great majority of his work depicts various sporting activities associated with horses, horsemen, the hunt, and horse racing. His serious work is elegant, polished, and includes little details that make it impossible to view a piece without finding something new and intriguing at each viewing.

However, it seems Mr. Alken had a sense of humor similar to that of Mr. Thelwell. Between 1780 and 1840, the material and style of clothing worn by those riding to hounds was transformed from the rough and billowy style of the country squire to the sculpted, flattering, and stylish fashions preferred by the young men of Town who sought to join the hunt in order to prove their masculinity and physical prowess. For these young urban Corinthians appearances, style, and the show of an athletic physique were paramount. For many, horsemanship came second.

There were a number of names given to these young toffs. The most prominent, however, was that of Meltonian. This is the term Henry Alken used to describe the riders in his humorous prints of the hunt. The name is derived from the town of Melton Mowbray in Leceistershire, a popular place for young Corinthians to gather and ride to hounds. Getting out of Town and spending time in the country engaged in hunting and shooting was a vital part of a young gentleman’s social life. I’ll do a longer post on the Meltonians soon as they definitely deserve a closer look.

However, Henry Alken’s prints concerning the Meltonian set leave his opinion of these gentlemen sportsmen in no doubt. In fact he did an entire series of prints entitled How to be a Meltonian.

I hope you have enjoyed a brief look at Henry Alken’s humorous prints. And I wonder, am I the only one who sees the similarity in vision between his work and that of Thelwell? Either way, both artists present views on horses and horsemanship that both entertain and delight.

Part Three of this post will take a look at Alken’s more serious prints. Stay tuned!

John Singer Sargent, the son of an American doctor, was born in Florence in 1856. He studied painting in Italy and France and in 1884 caused a sensation at the Paris Salon with his painting of Madame Gautreau. Exhibited as Madame X, people complained that the painting was provocatively erotic.

The scandal persuaded Sargent to move to England and over the next few years established himself as the country’s leading portrait painter. Sargent had no assistants; he handled all the tasks, such as preparing his canvases, varnishing the painting, arranging for photography, shipping, and documentation. He commanded about $5,000 per portrait, or about $130,000 in current dollars. Following are portraits representative of Sargent’s prolific, and much prized, portraiture featurning British subjects.

by Victoria Hinshaw

Opening December 4, 2020, sixty-five of the greatest paintings in the Royal Collection will hang in the Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace until January, 2022. That gives us a year to get to London and binge on the Real Thing, usually seen only inside the Palace where the very nice but firm guards keep the crowd moving right along.

Recently, as part of the program to renovate the Palace and update its outmoded systems, the Picture Gallery was vacated and the contents put into storage, except for the masterpieces chosen to be exhibited for the next thirteen months while this portion of the building undergoes its share of the Reservicing Program, a ten-year period of repairs.

The Picture Gallery was added to the Palace in the 1820’s by George IV to house his art collection. Architect John Nash, the King’s favorite, designed the room, also used for state receptions. It has been updated several times most recently in the 1950’s.

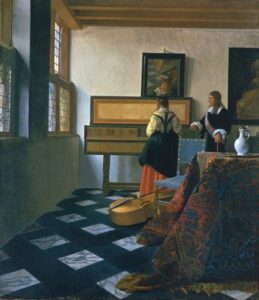

One of only 34 known Vermeer paintings, this canvas was acquired by George III in 1762. The relative simplicity of the scene concentrates the observer’s view on the figures and perhaps invites speculation on the relationship of the two. The delicacy of the light is a signature quality of Vermeer’s style and composition.

According to the description of the painting, “Claude was captivated by the effect of light in the landscape…we are transported directly into the scene.” This painting was probably acquired by Frederick, Prince of Wales, father of George III.

The description states “Reni dramatically conveys the foreboding of her passage from life to death…a shift from flesh and blood to cold marble.”

This painting was presented to Charles II in 1660 by the States of Holland and West Friesland upon his restoration to the throne. Titan stands as a giant of Italian painting for his realism, use of color and dramatic structure.

Canaletto is a favorite of the English, for both his Italian and his English scenes, all grand in scope but intricately detailed. George III acquired this painting in 1762 as part of the collection of Joseph Smith, British Consul in Venice. It portrays a celebration of the city’s Marriage with the Sea.

All these masterworks and more will be on view in the Queen’s Gallery long enough for us to get there, I hope! Once they are rehung inside the Palace Picture Gallery, more exhibitions from the Royal Collection will be mounted in the Queen’s Gallery. I have visited displays of Fabergé items, Leonardo drawings and artifacts, the Art and Love of Victoria and Albert, treasures from the courts of the first two Georges, and many more. All together they represent only a fraction of the total Royal Collection of 7,000 paintings, 500,000 prints, and 30,000 watercolors and drawings, plus sculptures, jewels, ceramics, photos, and manuscripts valued at well over $13 billion, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Hope I meet you there!

by Victoria Hinshaw

For those of us who love to poke around in British palaces, castles, stately homes, museums and all sorts of historical sites (that’s probably all of us), with a special interest in the Georgian and Victorian periods (most of us??), sooner or later we will begin to notice the recurring name of Francis Chantrey, a sculptor whose works are simply all over the place.

Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey (1781-1841) was not only a renowned and prolific artist, but also a philanthropist who left a bequest for the purchase of artwork for the nation. The income from investing the £105,000 from his legacy has been used to purchase hundreds of artworks by British artists for the nation’s museums and continues to this day.

Drawings Chantrey made of Sir John Soane, preparatory work for the bust Chantrey sculpted which today can be seen in Sir John Soane’s Museum, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, below.

Below, a sketch of the pedestal made by Chantrey for the Wellington statue.

Above, the Marble Hall at Holkham Hall in Norfolk, the estate of the earls of Leicester. On either side of the staircase (on the right behind the piano) are two busts by Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey.

Reproduction of a marble bust of Coke of Norfolk (1754-1842), by Chantrey, from 1829, which can be purchased from the estate at their website: http://www.holkhamsculpturereproductions.co.uk/

Coke of Norfolk, a great agricultural innovator, was the great nephew of Thomas Coke, and Coke of Norfolk was named 1st Earl of Leicester of the Seventh Creation in 1837.

Below, the reproduction of Chantrey’s marble copy of a bust of Thomas Coke, first Earl of Leicester (1697-1759) of the Sixth Creation. created by Louis Francoise Roubilliac (1705-1762). Both busts were sculpted to stand among the large collection of classical busts acquired by Thomas Coke and displayed at Holkham.

Above, Sir Joseph Banks in the British Museum, Botanist, Trustee and Benefactor, by Sir Francis Chantey, dated 1826.

Besides the dozens of busts Chantrey sculpted, which were highly prized and sought after, he did some touching works which displayed his skill in composition as well as compassion.

The Sleeping Children, 1817, above, in the Litchfield Cathedral, was commissioned by the widowed mother of the two dead girls, Mrs. Ellen-Jane Woodhouse Robinson. Most observers find it the finest of Chantrey’s works.

The lovely portrayal of Dorothea Jordan was commissioned from Chantrey by King William IV and completed in 1834. It has been displayed in Buckingham Palace since 1980. Mrs. Jordan, a leading actress of her day, was the long-time mistress of William IV when he was Duke of Clarence and bore him ten children, known by the surname FitzClarence.

This drawing of the anteroom of Chantrey’s sculpture gallery (30 Belgrave Place) shows its design by Sir John Soane for his friend, the sculptor.

This charming portrait of Mustard, Chantrey’s terrier, and his sculpting tools was presented to Queen Victoria by Lady Chantrey in 1842. According to the description in the Royal Collection, “The painting was commissioned in April 1835 by Chantrey, who sent Landseer a humorous letter, supposedly from Mustard. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1836 when it was admired by Queen Victoria.” After Chantrey’s death, his widow presented the painting to the Queen.

Also in the Royal Collection is this watercolour on ivory by Andrew Robertson (1777-1845), dated 1800. Purchased by Queen Victoria in 1880, it portrays Chantrey “Half-length, standing, facing slightly to the right, wearing a grey studio coat and dark blue waistcoat and holding a hammer, chisel and yellow dustcloth, beside his bust of George IV; grey-blue eyes, grey-brown hair; red curtains background.”

The painting above is The Burial of Sir Frances Chantrey by artist Henry Perlee Parker, 1841. It was badly damaged in a flood in 2007 at the Weston Park Museum, Sheffield, and had to be dried for more than a year before it was conserved. Chantrey is buried in St. James Church, Sheffield, near the village of his birth.