After dinner on our first night in Venice, Victoria and I decided to stroll on to St. Mark’s Square, or Piazza San Marco as it’s known locally. For a description of the Square and its buildings, I’ll quote Wikipedia: “The Square is dominated at its eastern end by the great church of St Mark.

“The church is described in the article St Mark’s Basilica, but there are aspects of it which are so much a part of the Piazza that they must be mentioned here, including the whole of the west facade with its great arches and marble decoration, the Romanesque carvings round the central doorway and, above all, the four horses (see photos above) which preside over the whole piazza and are such potent symbols of the pride and power of Venice that the Genoese in 1379 said that there could be no peace between the two cities until these horses had been bridled; four hundred years later, Napoleon, after he had conquered Venice, had them taken down and shipped to Paris.”

Note: After the Battle of Waterloo, during the Allied Occupation of Paris, the Duke of Wellington ordered that the horses be returned to the Basilica. A Captain Dumaresq, who had fought at the Battle of Waterloo and was with the Allied Forces in Paris, was selected by the Emperor of Austria to take the horses down from the Arc de Triomphe and accompany them on their return to their original place at St Mark’s. The horses remained in place over St Mark’s until the early 1980s, when the ongoing damage from growing air pollution forced their replacement with exact copies. Since then, the originals have been on display just inside the Basilica.

” . . . standing free in the Piazza, is the Campanile of St Mark’s church (last restored in 1514), rebuilt in 1912 ‘ com’era, dov’era ‘ (as it was, where it was) after the collapse of the former campanile on 14 July 1902.”

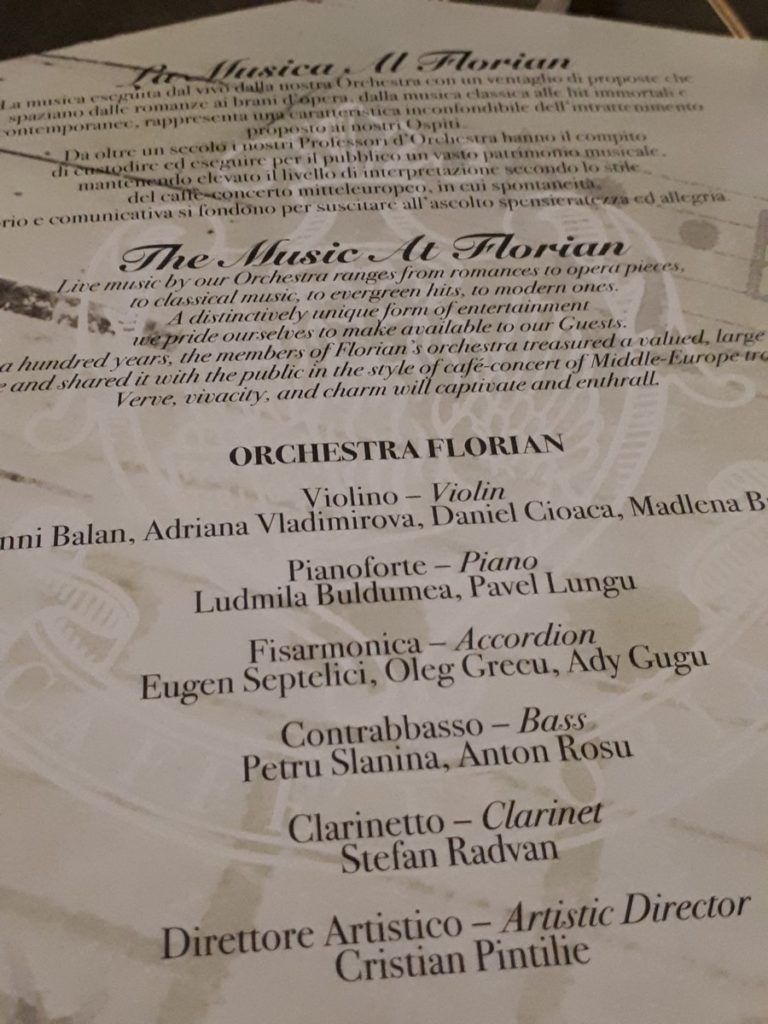

Another landmark in the Piazza is Florian’s, or Caffè Florian, which claims to be the worlds oldest coffee house, since 1720. In actuality, the first coffeehouse in London was opened in 1652 in St Michael’s Alley, Cornhill, by a Pasqua Rosée. Never mind, Florian’s can still claim it’s famous patrons over the centuries, including Casanova and Napoleon, Lord Byron, Wagner, Dickens and Henry Joyce. From Florian’s website: “While the finest wines and coffees from the Orient, Malaysia, Cyprus and Greece were being served inside, history was unfolding outside. Its windows witnessed the splendour and fall of the Serenissima Republic of Venice and the secret conspiracies against French and then Austrian rule; later, its elegant rooms were used to treat the wounded during the 1848 uprising. Right from the beginning, Caffè Florian has had a glittering clientele, including Goldoni, Giuseppe Parini, Silvio Pellico and many others.”

Naturally, Vicky and I couldn’t pass Florian’s without having a drink and listening to the band.

I ordered an amaretto and Vicky had a glass of prosecco. Once again, Venetian hospitality was on display in the form of the unexpected olives, biscotti and cookies that accompanied our drinks.

I ordered an amaretto and Vicky had a glass of prosecco. Once again, Venetian hospitality was on display in the form of the unexpected olives, biscotti and cookies that accompanied our drinks.

We sat companionably and enjoyed our drinks, the warm, starlit night and the music for quite a while. Again, very civilized. In fact, we liked Florian’s so well that we went back the next night, when my daughter Brooke arrived to join us in Venice. She seemed to enjoy it, too. If it was good enough for Lord Byron . . . .

You can listen to the band in this video I took on the night –

You can listen to the band in this video I took on the night –

Back in January of 2018, I was at Vicky’s condo in Naples, Florida, spending the week with her as at the time, I was living in the Panhandle. We sat in the living room, discussing plans for our upcoming trip to the UK in order to undertake some Wellington research at several archives in the south of England. Naturally, there would be a few weekends during the weeks we’d be away, meaning that the archives would be closed and we’d be free to do other things.

“Have you been to Beaulieu?” Vicky asked me.

“No. Put it on the list. Have you been to Osborne House? We could easily get there from Southampton.”

“Oh, great idea. I’ve never been. That’ll be fun!” For a while we were both silent, each of us checking our social media. After a bit, Vicky said, “You know, I’d love to go back to Venice. It’s been years since Ed and I went and I’d really like to see it again.”

“I’ve never been to Venice,” I said. And then we both looked up from our devices, our eyes met and it was a true Lucy and Ethel moment. In the space of the next couple of hours, we’d booked our hotel, flights and sketched out a working itinerary.

And so it came about that once we’d completed our Wellington research in England, we flew across the Channel and on to Venice.

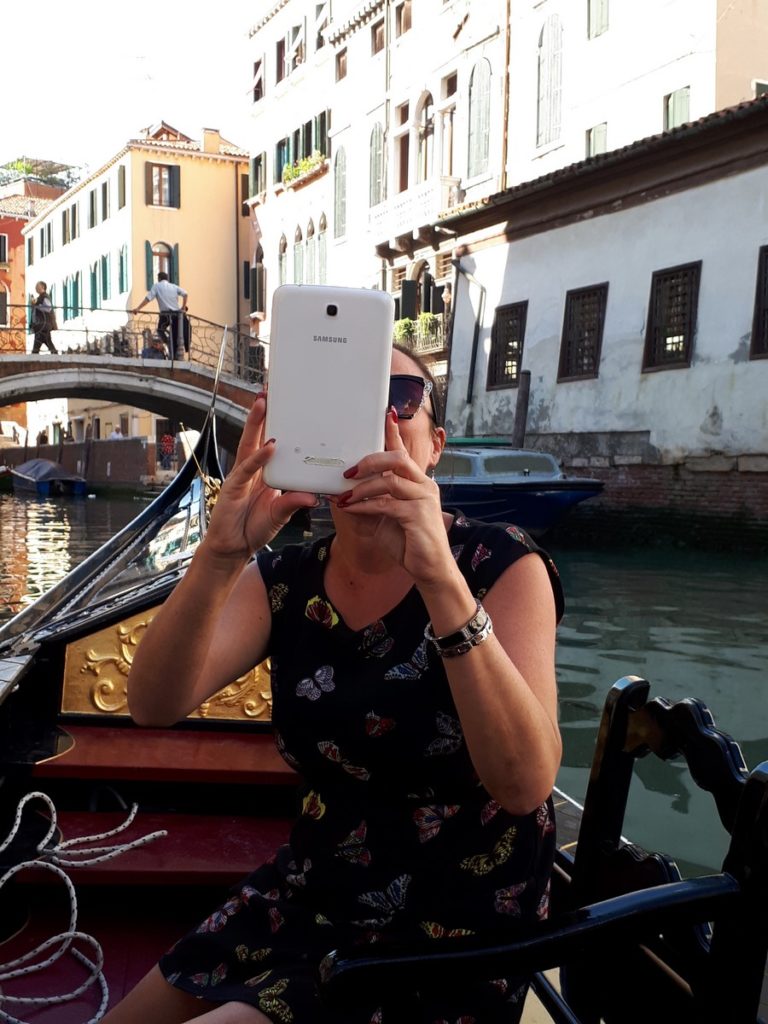

Upon arrival, Vicky and I walked for what felt like miles through the terminal to the water taxi departure point. I have to say, my first glimpses of Venice were not particularly impressive.

But things looked up once we’d arrived at our home for the next week, the Hotel Ai Cavalieri.

After check-in, we were shown to our room, which was quite large, well appointed and very red.

“Is it me, or do you feel like we’ve landed in a brothel, too?” I asked.

“It’s a lot of red. Look, even the chandeliers are red.”

“Everything is red. Every thing.”

Except for the bathroom.

Feeling in need of a drink, Vicky and I headed to the terrace bar and, as we were in Venice, ordered two glasses of prosecco. Which were served to us along with nuts, crisps and canapes. Very civilized, indeed.

Feeling in need of a drink, Vicky and I headed to the terrace bar and, as we were in Venice, ordered two glasses of prosecco. Which were served to us along with nuts, crisps and canapes. Very civilized, indeed.

Eventually, we roused ourselves and headed out into Venice in order to explore our neighborhood.

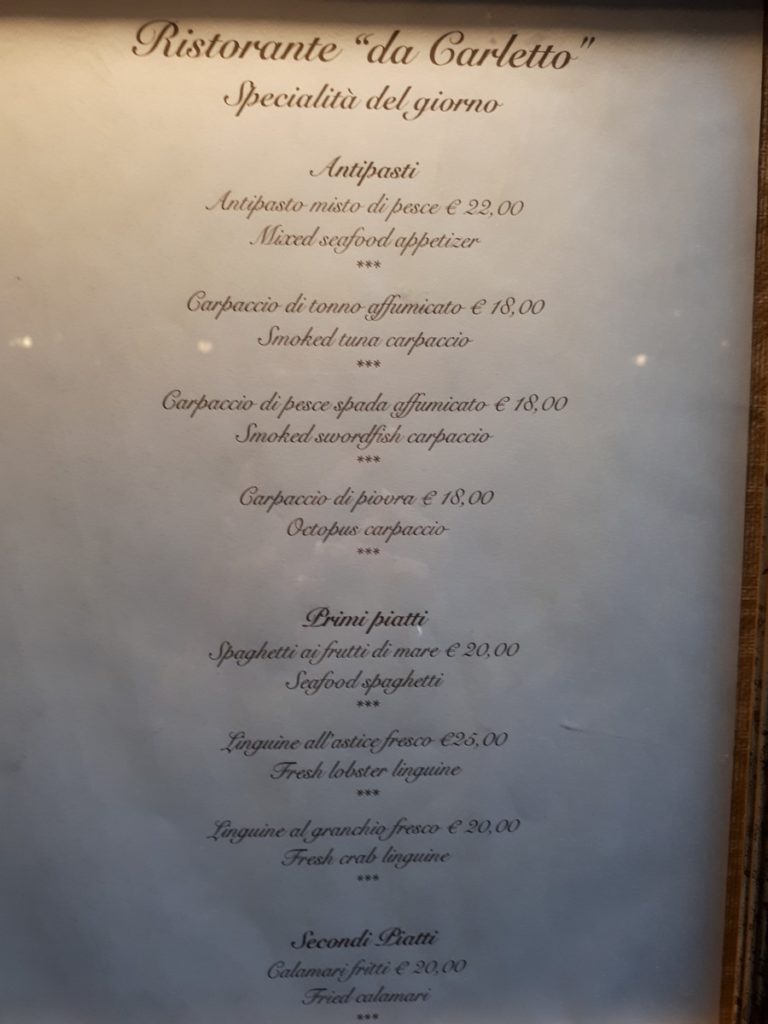

A bit later, we found a restaurant that had been recommended to us by our concierge.

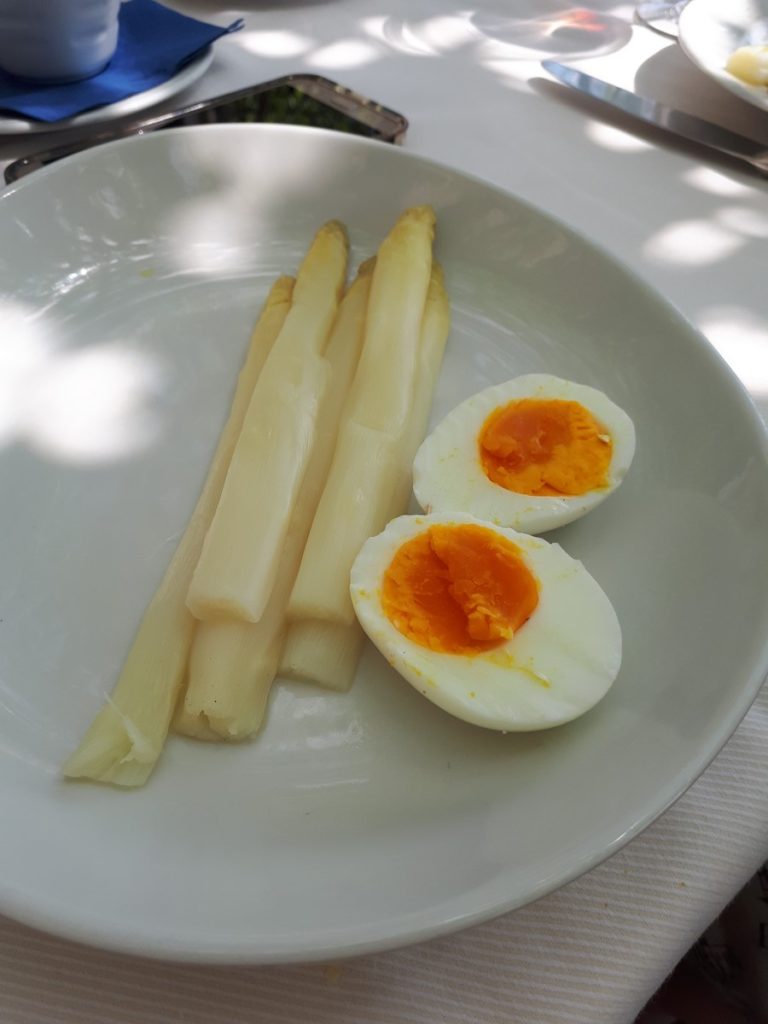

Vicky opted for the seafood risotto.

And I had the linguine with lobster. Both dishes were wonderful, the wine was excellent and the service was spot on. A really intimate spot with a neighborhood feel and freshly prepared food.

Finding your way around Venice by day is tricky enough, by night it’s almost impossible as everywhere looks the same as everywhere else. Literally. If you leave your hotel (any hotel) and make a left or a right (it doesn’t matter which) you will shortly come to a bridge over a canal. Crossing this, you will shortly come to a square which features shops, restaurants and the obligatory church. There will inevitably be a confusing number of streets, or alleyways, leading off of the square. Choose one (doesn’t matter which) and it will lead you to a canal which, once you cross the bridge, will bring you to another square that will look exactly like the square you just left. And so it goes. Eventually, Vicky and I did make it back to our hotel, and our red room, but of course, each time we ventured out, finding our way home again proved to be a challenge. Once, we left our hotel and walked for about twenty minutes, convinced we had Venice licked, only to find ourselves right back at our own front door. The adventure continues . . . .