In the run up to the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, we’ll first take a look at the connection between Wellington, Waterloo and Vauxhall Gardens. The Gardens, known for it’s dark walks, supper boxes, fireworks, balloon ascents and other assorted amusements, also regularly cashed in on events that captured the public interest, including the Battle of Waterloo. As best as I can discover, a recreation of the Battle was held each year, the event attracting thousands to the Gardens.

In 1817, the Battle of Waterloo was re-enacted with 1,000 soldiers participating, for which E. A. Theleur composed The Soldier’s Return, a “Military Divertissement.”

The European Magazine tells us that in 1824 –

“On the 19th of June, the anniversary of the battle of Waterloo was commemorated at these gardens by a grand military fete. Flags of all the nations of Europe waved from the trees, whose dark foliage was finely contrasted with the uncommon brilliancy of the lamps, of which there were upwards of 12,000 additional, arranged in various devices. A transparency of the Duke of Wellington presented itself in the most conspicuous part of the garden, flanked on each side by the word ‘Waterloo’ in variegated colours. In the ballet of the Chinese Wedding the Minuet de la Cour, the Gavutte, and a quadrille, were introduced by the pupils of Monsieur Hullin. The concert consisted of appropriate military songs, &c; and amongst the cosmoramas was one piece painted expressly for the occasion, representing the Battle of Waterloo. The fire-works were more than usually splendid, and concluded with a double glory of sixty-two rays, with ‘Wellington” in the centre, and the words ‘Long may he live.’ The company was numerous and respectable, comprising many persons of fashion; and, upon the whole, the fete passed off without considerable trial.”

The Battle of Waterloo, complete with horses, foot soldiers, and set scenes, was again presented at Vauxhall in 1827 and 1828. In 1827, Charles Farley, of Covent Garden Theatre, produced in the Gardens a representation of the Battle of Waterloo, with set-scenes of La Belle Alliance and the wood and chateau of Hougomont; also horse and foot soldiers, artillery, ammunition-wagons, &c.

From Bell’s Weekly Messenger for Sunday, June 26, 1831 –

“On Monday night the grand Annual Fete in commemoration of the Battle of Waterloo was given at these gardens. The proprietors of this elegant place of amusement exerted themselves to render the embellishments worthy of the occasion. Immediately on entering the gardens the name of Wellington presented itself in the brilliant illumination. Many thousand additional lamps, arranged in emblematical devices, were put up, interspersed with appropriate banners and devices. These attractions, added to the Concert, the Singers of the Alps, the Dioramic Views, the Optical Illusions, the new Cosmoramas, the Chin Melodist, and the German Whistler, seemed to give the company, which was numerous, a high degree of pleasure. The whole closed with a brilliant display of Fireworks and a Water Scene.”

What the Alps, a Chin Melodist and a German Whistler had in common with the Duke, or Waterloo, I have no idea. However, it seems that all who deigned to write about the event mention the fabulous fireworks. This next bit is from The Idler and Breakfast-Table Companion – “The anniversary of the “Battle of Waterloo” was celebrated on Monday last, by a magnificent gala at these gardens. The company were particularly select and numerous, and the entertainments of the most brilliant description;—the fireworks especially. The weather appears now to be settled; the worthy proprietors may therefore calculate on a host of visitors. A walk round the ‘Royal Property,’ on a fine evening, is a great treat.”

And, from The London Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, Etc 1828 –

“It happened to be the night of the re-celebration of the battle of Waterloo. For at Vauxhall it was found profitable to keep such festivals twice over, and the place was all in a blaze with emblems of military glory. The names of Wellington and Waterloo showed fiery off indeed in particoloured flame, and seemed a pattern for History to write of the hero—` With a pencil of light.’”

From The Works of Thomas Hood: Comic and Serious – “There was an abundance of illumination, but we think we have seen the ornaments more tastefully and airily disposed. The trophy shields were formal, and the crowns somewhat lumpish and heavy—light, as Dr. Donne would quibble, should be light— but there was a seasonable and splendid rose in June that did honour to the genius of the lamps.”

The tendency towards nit-picking evident in the passage above was expounded upon by the correspondent for The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction (1828) –

“On Wednesday, being a grand gala night in honour of the victory of Waterloo, we were induced to visit this place of resort—we would say of entertainment, had we found any; but a more miserably perverted source of public amusement than these same ‘Royal Gardens’ have become, it has never been our lot to endure. The entire character of the thing is altered, and glare and mummery have destroyed the original form and nature of the scene. Time was, when, from the bustling of business and the turmoil of the city, and even from the routs and crowded assemblies of fashionable life,—persons found an agreeable variety at Vauxhall. There was a lamp illumination, it is true—but here and there the turf was verdant, and every where the trees were green: there were sights—but they properly belonged to a rustic order, such as gentle transparencies, congenial landscapes, and at the utmost a fantoccini to divert the younger classes: there was music, too—but it was in the single orchestra, to which the promenader approached at times to hear a pretty ballad, and thus diversify the gossip-spent hour. Altogether, the Gardens were what they ought to be—essentially rural and recreative; now they are a hot, glittering, and noisy compound of all that is inferior in theatrical representations, shows, and vulgar nonsense-—a mixture of Astley’s, Bartholomew Fair . . . offensive to the eye and ear, and either tedious or distracting to the mind, as you happen to witness one performance, or be hurried to another. The company, too, which was always rather of a mixed description, is now much lowered, in consequence of the altered kind of the amusements. A mob of less attractive London materiel than we met on Wednesday can hardly be imagined. Low varlets, from the desk, the counter, and the shop-board, staring most impudently in the face of every woman, were only not so disgusting as usual, because the vast majority of the females were precisely of castes to whom such vulgarity could give no displeasure — in short, the Joes were well matched with the Jills; and a premium might have been safely offered for the discovery of any one gentleman or lady in ‘the hundred,’ or, indeed, of twenty persons of respectability in the whole mass. Then there was prepared for this worshipful company a poor vaudeville in the Row-tunder (as most of them called it), and a wretched ballet in the theatre. There were pictures, and cosmoramas, and Ching Louro, and a consort (also agreeably to the language of the place). But, above all, there was a mimic battle of Waterloo; and such a battle as ear never saw, nor eye heard! At the end of a walk, a crowd of men in uniform marched in and marched out; and Mr. Ducrow, dressed like the portrait of Buonaparte, capered and fidgetted about on a pale horse; while his Grace of Wellington curvetted on a piebald with a white face, which had nearly floored his excellent rider several times in the course of his masterly though limited evolutions on the field of war. After the footmen had walked here and there for about half an hour, and the horsemen had cantered up and down through the ten or a dozen trees and back again for as long a space of wasted time—the patient crowd of spectators waiting all the while and wondering what would come of it—a fierce attack was made upon a canvas ‘Hugomont,’ muskets were popped off, squibs thrown, and at last a rocket or a Chinese candle was supposed to set fire to the place, which was burnt down, to our great edification, and the curtain drawn. To this puerile and absurd spectacle succeeded the fire-works; and the weary visitors began to troop off as fast as they could, from so gay, so grand, and so delightful a treat—except a few of the most carnivorous and tipsy, who remained in congenial society—how long we cannot tell.

“The expense incurred in rendering Vauxhall so stupid and tiresome must be very considerable—but as complete success seems to have attended the effort, it is not to be grudged; and in these times of national distress the citizens of London, their wives and children, have no right to any relaxation. To be sure it must be paid for pretty smartly, if they are admitted to any comfort in these Gardens. Of old, a half-crown at the door, and the price of such comestibles as were devoured, were grumbled at, as tax enough; but now the account stands in a fairer form, because you are distinctly charged for every item separately, so that you know what you are paying for, and may choose or reject as you think fit. Thus Mr. Bull, from Aldgate, with Mrs. Bull, and only four of the younger Bulls and Cows, numbering six in all, makes good his entry at the cost of 1/. s.— Books to tell them what they are to see and hear, the when and the how, are 3s. — Seats for the vaudeville (average of modest places), 9s ditto for the ballet, ditto for the battle, 6s.—ditto for the fire-works, 6s., total, 21. 14. But, then, they are not charged for seeing the lamps; there is no charge for walking round the walks; there is no charge for looking at the cosmoramic pictures; there is no charge for casting a glance at the orchestra; there is no charge for staring at the other people; there is no charge for bowing or talking to an acquaintance, if you meet one—all these are gratis; and if you neither eat nor drink, there is no charge for witnessing those who do mangle the long-murdered honours of the coop, and gulp down the most renovating of liquors, be they hale or stout, vite vine, red port, or rack punch.

“Our account of these superb and captivating entertainments has, we regret to observe, stretched to a greater length than we could have wished; but when it is recollected that we do not intend to go to Vauxhall again very soon, we trust our particularity will be excused, and our tedious prolixity thought very appropriate to the subject.”

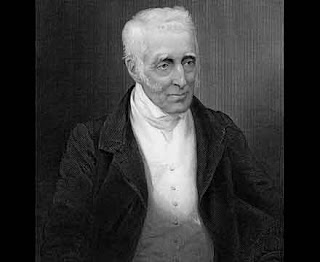

Despite such scathing reviews, Vauxhall Gardens continued to endure, and to mount recreations of the Battle. Perhaps the year 1849 was the crowning re-enactment, for the Duke (at left) himself made an appearance, as described by Edward Walford in Old and New London –

“Vauxhall Gardens, down to a very late date, still attracted ‘the upper ten thousand ‘—occasionally, at least. We are told incidentally, in Forster’s ‘Life of Dickens,’ that one famous night, the 29th of June, 1849, Dickens went there with Judge Talfourd, Stanfield, and Sir Edwin Landseer. The ‘Battle of Waterloo’ formed part of the entertainment on that occasion. ‘We were astounded,’ writes Mr. Forster, ‘to see pass in immediately before us, in a bright white overcoat, the ‘great duke’ himself, with Lady Douro (his daughter-in-law) on his arm, the little Lady Ramsays (daughters of the Earl of Dalhousie) by his side, and everybody cheering and clearing the way for him. That the old hero enjoyed it all there could be no doubt, and he made no secret of his delight . . but the battle was undeniably tedious, and it was impossible not to sympathise with the repeatedly and audibly expressed wish of Talfourd that ‘the Prussians would come up!’ It must have been one of the old duke’s last appearances in a place of amusement, as he lived only three years longer.”