by Victoria Hinshaw

For those of us who love to poke around in British palaces, castles, stately homes, museums and all sorts of historical sites (that’s probably all of us), with a special interest in the Georgian and Victorian periods (most of us??), sooner or later we will begin to notice the recurring name of Francis Chantrey, a sculptor whose works are simply all over the place.

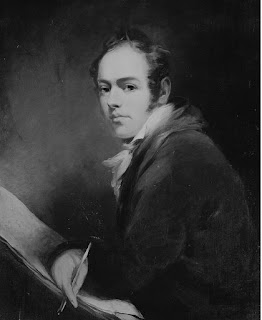

Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey, by Thomas Phillips, 1818 (NPG)

Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey (1781-1841) was not only a renowned and prolific artist, but also a philanthropist who left a bequest for the purchase of artwork for the nation. The income from investing the £105,000 from his legacy has been used to purchase hundreds of artworks by British artists for the nation’s museums and continues to this day.

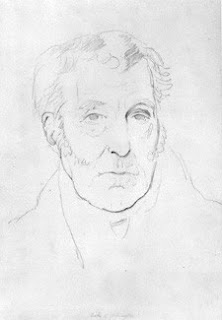

Chantrey self portrait, 1810, Tate Britain

The UK’s National Portrait Gallery has hundreds of works by Chantrey himself, from sketches executed as preparation for his sculptures, to marble busts of leading men of his generation.

Drawings Chantrey made of Sir John Soane, preparatory work for the bust Chantrey sculpted which today can be seen in Sir John Soane’s Museum, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, below.

Close-up of the bust of Sir John Soane

Last year, at the Yale Center for British Art, Diane Gaston, a well-known Regency author, and Victoria posed with a Chantrey bust of George IV.

As so often in Georgian-era portraits, the subject is wearing a Roman-style toga. And without being unrealistic, somehow the expression on the King’s face seems to me quite representative of his character. Unlike the overly flattering pictures by others, particularly Sir Thomas Lawrence, this Chantrey bust gives us a hint of the dichotomy in George IV: one the one hand selfish, narcissistic and extravagant — but on the other hand, a great builder and connoisseur of the arts.

This Chantrey bust is one of several similar versions he and his studio produced, dated 1827.

Chantrey’s equestrian statue of George IV

George IV and the royal family were frequent patrons of Chantrey. His bronze state of Geogbe IV on horseback can be found in Trafalgar Square, as above. Below is George IV in the center of the Grand Vestibule of Windsor Castle’s State Rooms, flanked by mounted knights.

The magnificent statue of the mounted Duke of Wellington by Chantrey stands outside the Royal Exchange in the City of London.

Below, a sketch of the pedestal made by Chantrey for the Wellington statue.

Chantrey’s sketch of the Duke of Wellington for a bust.

Born near Sheffield, Francis Chantrey was the son of a carpenter and became an apprentice to a woodcarver. His skill and talentset him apart, and he was given lessons in painting. He was a able to earn enough as a portrait painter to move to London, where by 1804, he was included in exhibitions at the Royal Academy

Chantrey Self-Portrait, NPG

In a few years, he devoted himself mainly to sculpture. He married in 1807, and soon was doing commissions for naval officers and the Greenwich Hospital. He visited Italy in 1819 and associated with the leading artists of his day. He was knighted in 1835 by William IV. When he died, he was buried in a tomb he had constructed for himself in St. James Church, near Sheffield.

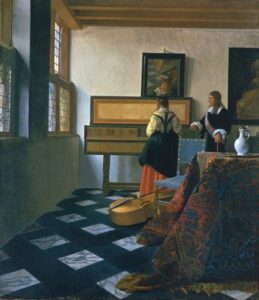

Above, the Marble Hall at Holkham Hall in Norfolk, the estate of the earls of Leicester. On either side of the staircase (on the right behind the piano) are two busts by Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey.

Reproduction of a marble bust of Coke of Norfolk (1754-1842), by Chantrey, from 1829, which can be purchased from the estate at their website: http://www.holkhamsculpturereproductions.co.uk/

Coke of Norfolk, a great agricultural innovator, was the great nephew of Thomas Coke, and Coke of Norfolk was named 1st Earl of Leicester of the Seventh Creation in 1837.

Below, the reproduction of Chantrey’s marble copy of a bust of Thomas Coke, first Earl of Leicester (1697-1759) of the Sixth Creation. created by Louis Francoise Roubilliac (1705-1762). Both busts were sculpted to stand among the large collection of classical busts acquired by Thomas Coke and displayed at Holkham.

Above, Sir Joseph Banks in the British Museum, Botanist, Trustee and Benefactor, by Sir Francis Chantey, dated 1826.

Also displayed in the British Museum, Chantrey’s bust of his collaborator and mentor, the famous 18th c. sculptor Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823).

Besides the dozens of busts Chantrey sculpted, which were highly prized and sought after, he did some touching works which displayed his skill in composition as well as compassion.

The Sleeping Children, 1817, above, in the Litchfield Cathedral, was commissioned by the widowed mother of the two dead girls, Mrs. Ellen-Jane Woodhouse Robinson. Most observers find it the finest of Chantrey’s works.

The Royal Collection

The lovely portrayal of Dorothea Jordan was commissioned from Chantrey by King William IV and completed in 1834. It has been displayed in Buckingham Palace since 1980. Mrs. Jordan, a leading actress of her day, was the long-time mistress of William IV when he was Duke of Clarence and bore him ten children, known by the surname FitzClarence.

Bridgeman

This drawing of the anteroom of Chantrey’s sculpture gallery (30 Belgrave Place) shows its design by Sir John Soane for his friend, the sculptor.

Pen, Brush and Chisel: The Studio of Sir Francis Chantrey by artist Sir Edwin Landseer (1803-73), Royal Collection

This charming portrait of Mustard, Chantrey’s terrier, and his sculpting tools was presented to Queen Victoria by Lady Chantrey in 1842. According to the description in the Royal Collection, “The painting was commissioned in April 1835 by Chantrey, who sent Landseer a humorous letter, supposedly from Mustard. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1836 when it was admired by Queen Victoria.” After Chantrey’s death, his widow presented the painting to the Queen.

Queen Victoria, marble, 1841, by Sir Francis Chantrey, Royal Collection

Chantrey created portraits of four British sovereigns. Above, his last work, a bust of Queen Victoria, was Prince Albert’s favorite portrayal of his wife

Also in the Royal Collection is this watercolour on ivory by Andrew Robertson (1777-1845), dated 1800. Purchased by Queen Victoria in 1880, it portrays Chantrey “Half-length, standing, facing slightly to the right, wearing a grey studio coat and dark blue waistcoat and holding a hammer, chisel and yellow dustcloth, beside his bust of George IV; grey-blue eyes, grey-brown hair; red curtains background.”

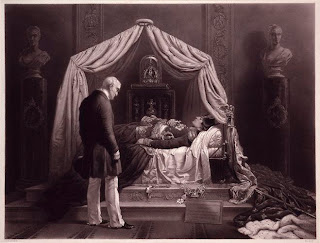

The painting above is The Burial of Sir Frances Chantrey by artist Henry Perlee Parker, 1841. It was badly damaged in a flood in 2007 at the Weston Park Museum, Sheffield, and had to be dried for more than a year before it was conserved. Chantrey is buried in St. James Church, Sheffield, near the village of his birth.