|

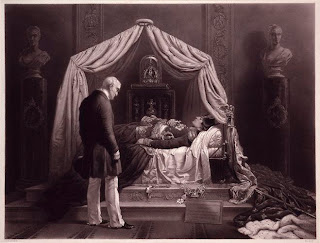

| The Duke of Wellington visiting the Effigy and Personal Relics of Napoleon at Madame Tussaud’s by James Scott, after Sir George Hayter – National Portrait Gallery Generally speaking, when one thinks about the Duke of Wellington, one seldom thinks of him in connection with trivial amusements. Rather, the formidable soldier and stern politician come to mind. However, the Duke was occasionally up for a jolly time and he had a great interest in new inventions and various amusements of the day. When the Great Exhibition of 1851 opened, the Duke went to see it nearly every day. In Struggles and Triumphs: or, Forty Years’ Recollections of P. T. Barnum by Phineas Taylor Barnum (1871), Mr. Barnum relates the following anecdote about the Duke: “On my first return visit to America from Europe, I engaged Mr. Faber, an elderly and ingenious German, who had constructed an automaton speaker. It was of life-size, and when worked with keys similar to those of a piano, it really articulated words and sentences with surprising distinctness. My agent exhibited it for several months in Egyptian Hall, London, and also in the provinces. This was a marvellous piece of mechanism, though for some unaccountable reason it did not prove a success. The Duke of Wellington visited it several times, and at first he thought that the `voice’ proceeded from the exhibitor, whom he assumed to be a skillful ventriloquist. He was asked to touch the keys with his own fingers, and after some instruction in the method of operating, he was able to make the machine speak, not only in English but also in German, with which language the Duke seemed familiar. Thereafter, he entered his name on the exhibitor’s autograph book, and certified that the `Automaton Speaker’ was an extraordinary production of mechanical genius.” The Duke of Wellington was also a great fan of Madame Tussaud’s and visited her waxworks often to see the exhibits and/or to take tea with Madame herself. He left standing instructions that he was to be told whenever a new addition to the rooms was installed. As executor of the will of George IV, Wellington was responsible for giving Madame Tussaud the monarch’s coronation robes for her exhibit. Surprisingly, the Duke’s favorite exhibit at the Wax Work was that of Napoleon. From a contemporary book titled The Curiosities of London, we learn that Madame Tussaud’s Napoleon exhibit contained the following: “Napoleon Relics. — The camp-bedstead on which Napoleon died; the counterpane stained with his blood. Cloak worn at Marengo. Three eagles taken at Waterloo. Cradle of the King of Rome. Bronze posthumous cast of Napoleon, and hat worn by him. Whole-length portrait of the Emperor, from Fontainebleau; Marie Louis and Josephine, and other portraits of the Bonaparte family. Bust of Napoleon, by Canon. Isabey’s portrait Table of the Marshals. Napoleon’s three carriages: two from Waterloo, and a landau from St. Helena. His garden chair and drawing-room chair. “The flag of Elba.” Napoleon’s sword, diamond, tooth-brush, and table-knife; dessert knife, fork, and spoons; coffee-cup; a piece of willow-tree from St. Helena; shoe-sock and handkerchiefs, shirt, &c. Model figure of Napoleon in the clothes he wore at Longwood; and porcelain dessert-service used by him. Napoleon’s hair and tooth, etc.” As to Wellington’s visits to the Exhibit, we have the following passage from The History Of Madame Tussaud’s ( Originally Published 1920 ) –

Early one morning, soon after the Exhibition had been opened for the day, Joseph, Madame Tussaud’s son, who had been wandering through the rooms, as was his habit, perceived an elderly gentleman in front of the tableau representing the lying-in-state of Napoleon I. The model of the dead exile rested—as it does down to this very day—on the camp bedstead used by Napoleon at St. Helena, and was dressed in the favourite green uniform, the cloak worn at Marengo (bequeathed by Napoleon to his son) lying across the feet. In the hands, crossed upon the chest, was a crucifix. In those days it was the custom to lower at night the curtains that enclosed the bed, in order to exclude the dust, whereas now the whole scene is encased in glass.

Observing that the visitor was desirous of seeing the effigy, and no attendant being at hand, Joseph Tussaud raised the hangings, whereupon the visitor removed his hat, and, to his great surprise, Joseph saw that he was face to face with none other than the great Duke of Wellington himself.

There stood his Grace, contemplating with feelings of mixed emotions the strange and suggestive scene before him. On the camp bed lay the mere presentment of the man who, seven-and-thirty years before, had given him so much trouble to subdue. No feeling of triumph passed through the conqueror’s mind as he looked upon the poor waxen image, too true in its aspect of death; he rather thought upon the vanity of earthly triumphs, of the levelling hand of time, and how soon he, like his great contemporary, might be stretched upon his own bier.

Mr. Joseph Tussaud used frequently to recall this dramatic meeting between the Iron Duke and the effigy of his erstwhile foe, and to imagine the feelings of the old General as he gazed upon the couch. It was probably the first of the Duke’s many visits to the Exhibition. A few days after this most interesting visit Mr. Tussaud, who was an old friend of Sir George Hayter, related the incident to that artist. Hayter was immediately struck with the potential value of the event for the production of a painting of the historic scene, and the Tussaud brothers at once commissioned him to execute the work for them. Sir George thereupon communicated the idea to the Duke, who readily responded, and offered to give the necessary sittings. We have the sketches made by Hayter in preparation for the work, and among them appears a drawing of Joseph Tussaud himself, although he does not enter the actual picture. Hearing that the artist was making progress with the painting, the Duke visited his studio, and, having expressed himself warmly in appreciation of the picture (the figures had been but lightly limned in at the time), said: “Well, I suppose you’ll want me to sit for my picture here?”

Hayter has given us a most characteristic portrait of Wellington as he then appeared. He is dressed in his usual blue frock-coat, white trousers, and white cravat, fastened with the familiar steel buckle. He stoops a little as was his wont, his head is lightly covered with snow-white hair, and his manly features are marked with an expression of mingled curiosity and sadness as, hat in hand, he looks upon the recumbent Napoleon. The picture was completed early in December, 1852, and has been on view in the Napoleon Rooms at the Exhibition ever since.

The engravings of the picture have been circulated in thousands throughout the world, and, strange to say, they are exceedingly popular in Austria. It is an interesting fact that the painting in question was the last portrait for which the Duke ever sat. When the Duke himself died, Madame Tussaud’s advertised “A full length model of the Great Duke, taken from Life during his frequent visits to the Napoleon Relics.” Wellington himself would have been least surprised to learn that Madame Tussaud had added his likeness to her collection upon his death. Unfortunately, I’ve yet to find an engraving of the Duke’s tableaux, but we do have the following description found in Our Young Folks: An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls, Volume 8 (1872) By John Townsend Trowbridge: “In a side room adjoining the long gallery lies the great Duke of Wellington in state. An awful feeling came over me, as if I were in the presence of the dead, as I looked upon that noble form, lying still and cold, with all the “pride of heraldry and pomp of power” around him, insensible alike to both. As he lay there on his tented couch of velvet and gold, it seemed as if that must be the “Great Duke,” and not a waxen image only, that never lived nor spoke. Among the numerous portraits which adorn the walls is a very fine one of the duke visiting the relics of Napoleon, which are shown in another room.” Many a person has recorded his or her feelings about the Duke of Wellington’s funeral carriage, above, a great monstrosity of a thing weighing 18 tons and made from the French guns taken in battle and designed by Prince Albert himself in a misguided attempt to pay a fitting tribute to the Duke. All agree that it was pretty much a hideous object. Charles Dickens wrote, “For form of ugliness, horrible combination of colour, hideous motion, and general failure, there never was such a work achieved as the Car.” After the funeral, there was a general debate as to what to do with the thing. The question even made its way to Parliament, as mentioned in a book called Stray Papers, published in 1876 – During a Parliamentary debate, Mr. Layard said, that there was a hideous piece of upholstery under cover opposite Marlborough House at the disposal of anybody who would take it; but, as nobody would take it, they were now asked to vote £840 for its removal to St. Paul’s, where it would be placed beneath one of the crypts. He alluded to the car used at the funeral of the late Duke of Wellington, and that which nothing more hideous had ever been invented. The best thing would be to give it to Madame Tussaud, or, if she would not take it, to burn it. The carriage now rests at Stratfield Saye. But, the same book goes on to tell us that: Several years ago, a figure of the late Duke of Wellington stood under one of the skylights in the principal room (at Madame Tussaud’s.) By some unaccountable oversight, the attendant omitted to draw the blinds on one occasion when shutting up for the night, and next morning the hot rays of a July sun fell on the Duke’s countenance with such fervour that his Grace’s nose began to run, and, by the time the doors were opened, had disappeared completely. So much of the figure being destroyed, restoration to its original form was found to be impossible. There used to be a figure of the Duke of Wellington, and Napoleon, on display at Madame Tussaud’s in London, but when I was there recently I didn’t see it. Then again, the place was so crowded I might have missed it. It’s good to think that the Duke is still around, even in storage, and might be brought out again soon. Since this post was originally published several years ago, Geri Walton has written an excellent blog post on Madame Tussaud’s Napoleon Relics. You’ll find it here.

|

Category: Napoleon

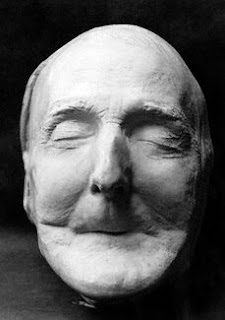

A MACABRE LOOK AT DEATH MASKS

|

| Richard Brinsley Sheridan |

Originally published October, 2010

Recently, I came across a book online called The Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks: A Pictorial Guide by John Delaney, held in the Manuscripts Division in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton University Library. The making of death masks became popular in the 1800s, but the practice has much older roots. The first masks and effigies made in wax directly from the features of the deceased date from medieval Europe. Personally, I don’t get death masks. All of the people from whom death masks were taken were prominent people who had had numerous portraits and busts taken during their lifetimes. Why not remember them thusly, in the prime of their lives, rather than take an image of them in old age – withered, toothless and, more often than not, after having just suffered hours of agony? Perhaps my aversion to death masks is a woman thing. After all, I’ve yet to come across the death mask of a female.

|

| Making a plaster death mask, New York circa 1908, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress |

In a volume titled, “The life of Richard Owen”, by Rev. Richard Owen (1894) there is reference to the death mask above in a letter written on November 13, 1852, to Mr. Thomas Poyser, of Wirksworth : ” I have been particularly favoured in respect of the remarkable solemnities in honour of the memory of the great Duke. The present amiable inheritor of the title called on me last Wednesday to request that I would call on him to see the cast that had been taken after the Duke’s demise, and give some advice to a sculptor who is restoring the features in a bust, intending to show the noble countenance as in the last years of the Duke’s life. It is a most extraordinary cast. It appears that the Duke had lost all his teeth, and the natural prominence of the chin and nose much exaggerates the intermediate space caused by the absorption of the alveoli. He of course wore a complete set of artificial teeth when he spoke or ate. My last impression of the living features is a very pleasing one. I brought it away vividly in my mind from Lord Ellesmere’s great ball last July.”

This death mask was on display at the Royal United Services Institute Museum in London for many years prior to 1973, when the mask was sold. You decide . . . . . here is one of the last portraits of Napoleon, painted by Sir Charles Lock Eastlake on board the ship Bellerophon.

And here is an enlargement of the face

Viola. Ze case it has rested. At least in my mind.

For more on death masks, including instructions on how to make one, visit Carlyn Becchia’s Raucous Royals blog.

Napoleon Invades Russia, June 24, 1812

Another bicentenary is here, though its connection to Britain is not quite direct. However, the failure of Napoleon’s Russian invasion and the destruction of a large part of his army contributed to his ultimate defeat(s) by the allied nations led by Great Britain.

With the benefit of hindsight, historians have spent two hundred years pointing out the deficiencies in Napoleon’s goals, strategies and execution. I have to admit most of my knowledge about Napoleon’s Russian campaign was learned in Tolstoy’s War and Peace, published in 1869.

And since it is incredibly long (though also brilliant), I skimmed (or skipped) large sections. So my limited knowledge is, perhaps, more attributible to the 1956 film of War and Peace. I love that movie, starring Audrey Hepburn as Natasha, Mel Ferrar as Prince Andrei, and Henry Fonda as Count Pierre Bezukhov.

As everyone knows, Napoleon’s campaign in Russia was a total disaster. Numbers vary but about half a million soldiers of the Grand Armee marched into Russia and only a fraction returned by the end of 1812. Well before the Russian campaign, Arthur Wellesley, later named first Duke of Wellington, began to turn the tide in the Peninsular War, invading Spain from Portugal in January, 1812. Wellington and the allies won the Battle of Salamanca, June 17-22, 1812. French Marshall Soult and his defeated troops fought on but slowly withdrew into France.

On June 24th, having heard nothing about the British and Allied victory in Spain, Napoleon’s troops crossed the river Niemen into what is now Lithuania, then Russian Poland. The Russians, greatly outnumbered, usually retreated or conducted brief skirmishes instead of standing and fighting as Napoleon’s enemies usually did. In doing so, the Russians drew the French deeper and deeper into their sparsely populated regions, completely fouling up supply lines for the rapidly moving French. By mid-October, the French encircled Moscow, the capital. The Russians evacuated the city — and it burned, whether set afire by the fleeing citizens or by the invading troops no one can know. Probably both.

The Wellington Connection: Theme Parks

There are plans afoot to build “Napoleonland” in France. And, no, before you ask . . . I’m not kidding.

Funding is as yet unsecured, but preliminary plans are for the theme park to be built at the site where Napoleon defeated the Austrians in the Battle of Montereau in 1814 in Montereau-Fault-Yonne just south of Paris. The six-day battle was the nation’s last military victory over the Austrians.

Having apparently not gotten the memo telling the organizers of the park that Napoleon lost at Waterloo, they plan to re-create the Battle of Waterloo on a daily basis and visitors may even be able to take part in the reenactments. They will also be able to take in a water show recreating the Battle of Trafalgar, a la the entertainments once staged at London’s Vauxhall Gardens.

A museum, a hotel, shops, restaurants and a congress are all expected to be built at the theme park. French politician Yves Jego, who is backing the project, hopes that construction work can get underway in 2014 and that the park will open its doors in 2017. One has to assume that Jego will not be seeking re-election, as things go from bad to worse in the bad taste department with further plans to include a re-creation of the killing of Louis XVI, France’s last King, who died after being guillotined during the Revolution and. . . . . . . yet another attraction which will allow visitors to ski around the bodies of soldiers and horses frozen on the battlefield.

Why are there no plans to build Artie World instead?

Researching the 30th Regiment by Guest Blogger Carole Divall

Victoria and I met author Carole Divall at Waterloo this past June and Carole was kind enough to agree to do a guest blog for us on her research into the Napoleonic Wars and the 30th Regiment.

When I started researching the 30th (Cambridgeshire) Regiment fifteen years ago, I had no idea where my investigations would take me. Suffice to say, at the time I was merely looking for a means of moving my general interest in the period of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars into something more specific. Initially, I merely dabbled as time allowed. What I discovered, however, was a wealth of material: official documents, newspaper reports, journals and letters which brought to life several thousand men who demonstrated all that is good, bad and ugly in the human race. It was then that I decided their experiences should be recorded in a book.

According to Ralph Waldo Emerson, “There is properly no history, only biography.” To write a history of a regiment is to write the biographies of the men of that regiment. The more I researched, the less I was satisfied merely with what the 30th did. Instead, I wanted to discover what made the men tick – officers, NCOs and other ranks. And I certainly found everything from the dedicated officer and zealous private to the dishonest NCO and criminal “king’s hard bargains”.

Even my first book, Redcoats Against Napoleon, which focused on the deeds of the 30th between 1789 and 1817 (with an extension to 1829 to cover events in India) adopted a more biographical perspective than the conventional military history approach. I wanted the reader to be able to share the experiences of the men who fought from Toulon (1793) to Waterloo, whether it was suffering the heat and thirst of Egypt, the incessant rains of Portugal, or the desperate stand in the center of Wellington’s line at Waterloo.

My second book, Inside the Regiment, which comes out next February, attempts to open the door on the private life of the 30th, and explore how it functioned on a day-to-day basis. For example, what was it about the command style of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton that made him such an inspiring leader of men? What exactly were the offenses of the king’s hard bargains? Were all the men in the ranks merely “the scum of the earth?” What was it like to be a recruit? How did the officers spend their leisure time? Were the surgeons really as incompetent as history suggests? And what about the women? Did they have a part to play in the life of the regiment?

Like all biographers, I hope I have brought my subject (or, more accurately, subjects) into the limelight. The 30th were only one of a hundred infantry regiments. Although they were unique, they were also representative of all those other units which fought for king and country, for duty, for the chance of plunder – but, most of all, for their regiment.

If you would like to know more about the 30th Regiment, look on my website for details of what the two battalions were doing exactly a hundred years ago.