It was a cold, wet, foggy day when we visited the Tower of London – a day chock full of atmosphere and history.

Of course, the Tower is a must see for any first time visitor to London and that’s why it was on our agenda, so that Greg could take it all in. Not surprisingly, the Duke of Wellington made an appearance here, as well, having served as Constable of the Tower for 26 years. As I said to Greg, “You’ve got to give it to Artie, he had his fingers in so many pies.”

The Waterloo Barracks at the Tower were built while Wellington was Constable and named after his famous victory over Napoleon. The building replaced the Grand Storehouse which was destroyed by fire in 1841 and the foundation stone, laid by the Duke of Wellington in 1845, can be seen at the north-east end of the building. The fire, which had taken place on October 30, 1841, at 10:30 p.m. was caused by an overheated flue in the Bowyer Tower. Thirty minutes later, the Bowyer Tower was almost completely destroyed, and the fire had spread to the armories and storehouse to the east of the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. By midnight the armories were burning so furiously that the heat caused the lead pipes to melt on the walls of the Great Tower. The Brick Tower then caught fire, and flames threaten to burn Martin Tower where the Crown Jewels of England were kept. The Keeper of the Jewel House only had the key to the outer room (the Lord Chamberlain had the other keys). Water was sprayed on the walls of Martin Tower as firemen tried to keep the walls cooled down until the Crown Jewels could be removed. One firemen was killed when he was hit by a piece of falling stone. Using crowbars, policemen bent back the bars from in front of the Crown Jewels. A brave policeman handed out the Crown Jewels piece by piece. He did not leave, even though his uniform was charred from the heat, until everything, except a silver font which would not fit through the bars, had been saved. The fire was finally under control at 3:15 a.m., but the two armories, storehouse, Bowyer Tower, and the Brick Tower were destroyed, and both the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula and the Great Tower (White Tower) were badly damaged. The Duke of Wellington was Tower Constable at the time of the fire (he was appointed in 1826), and with the help of Prince Albert, Wellington spearheaded a campaign to get government funds to restore and rebuild the Tower of London. This massive project lasted throughout the rest of the 19th century.

At the time Wellington became Constable in 1826, the post of Yeoman Warder could be bought for 250 guineas, or even inherited within families. The Duke brought these practices to an end, making appointments based on distinguished military service. He also made improvements to the Tower itself. By 1841, in the words of the Surgeon-Major, the moat was ‘impregnated with putrid animal and excrementitious matter…and emitting a most obnoxious smell.’ Several men from the garrison died and 80 were in hospital due to the poor water supply. Local cholera outbreaks were blamed on the moat. The duke drained it and created the dry ditch, or fosse, that visitors see today.

|

| Lion’s skull found in drained Tower moat |

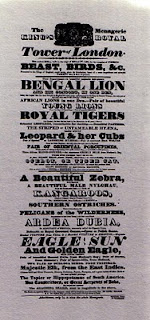

The menagerie at the Tower was once filled with exotic animals and was a popular tourist attraction. It was established by King John, who reigned in England from 1199-1216, and is known to have held lions, elephants, leopards, camels, ostrich and bears. The menagerie was finally closed in 1835, on the orders of the Duke of Wellington, and the remaining animals were moved to the Zoological Society’s Gardens in Regent’s Park, now known as London Zoo.

|

| A list of animals in the menagerie during the reign of George IV |

To learn more about the history of the Tower menagerie, click on the book cover.

Finally, the Duke made some improvements to the portcullis at the Bloody Tower, above. Look closely and you’ll see spiked, black iron bars on either side of the doorway at about knee height. The Duke ordered these to be installed so that the guards would no longer be able to lounge against the wall and smoke whilst on duty – ha!