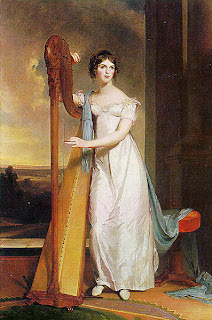

Tom Sully: As a young man I found Victorian art cloying. I decided to go to art school in California where few had ever heard of Thomas Sully. When I arrived in New York afterwards, theories of deconstruction held sway in the art world. While all my peers were making conceptual art, I turned to illustration for my living, since you still needed to know how to draw for that. My first portrait commission was from The New Yorker, who hired me to paint a singer performing at The Rainbow Room. It was then that I took Sully’s Hints To Young Painters down from the shelf and got to work.

Tom Sully: Garland, 2012, oil on linen, 24 x 20

NOL: Have there been other people in the arts in your family?

TS: Sully’s parents were actors and all his siblings were actors and musicians. His children painted – the most promising, another Thomas, unfortunately died young. I’m descended from Sully’s son Alfred, an army general who painted Native American scenes while serving in the Dakotas. The most recent artist family member of note is Thomas O. Sully, a celebrated New Orleans architect who bridged the 19th and 20th centuries. His grandfather, the portraitist’s brother, had moved to Louisiana in the early 1800s. When he wasn’t designing Queen Anne-style Garden District mansions, the architect loved to hunt and fish in the Louisiana countryside. I feel a connection to him when I go into the bayous and swamps to find subjects for landscapes.

Tom Sully: After Henry Inman, 2011, oil on linen, 15 x 12 in.

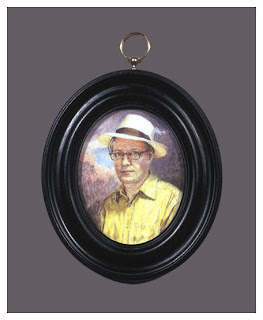

NOL: You have painted portraits, landscapes, and other relatively large-scale oil paintings for years. What inspired you to paint portrait miniatures?

TS: In 2001 I saw an amazing traveling exhibition. Love and Loss, American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures, organized by Robin Jaffee Frank at Yale University Art Gallery. What intrigued me was that these are intimate portraits, full of heartfelt, personal associations. These charged images sustained a current between people otherwise separated by the vagaries of life and geography, the daily routine, or even death. An image of a family member or loved one, small enough to be held in the hand and carried on your person, can take on the properties of a talisman. When worn, they become a public emblem of affection. The

y were and can still be used today as a catalyst in courtship. To me, this is portraiture at its best and about as far away from the institutional boardroom portrait as you can get! The show included a miniature Sully had painted to mourn the death of his mother. Of course, the technique and sheer artistry of these paintings is incredible. It took me awhile to track down the materials and get up the nerve to work so small.

NOL: Do you paint in the traditional technique with tiny stippled dots of watercolor on ivory?

TS: Yes, I use a combination of stippling and hatching, applying small amounts of paint and waiting for each layer to dry before adding the next, gradually and patiently building up richness and depth while achieving a likeness. A little like the rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland, this small space becomes your world.

Tom Sully: Susan Tying Her Necklace, 2011, watercolor on ivory, 2 7/8 x 2 3/8 in.

NOL: Do you work from photographs or do your miniature subjects pose while you sketch or paint?

TS: I like to work from photographs that I take myself. I find photography a useful conceptual tool – we can try out different angles on the face, different hairstyles, clothing, jewelry and lighting until we are happy with the composition in one or more of them. The photos do not then become “the be all and end all” but what Degas called an “aide de memoire.” While I paint, I improve on the photos. Sentiment, emotion and empathy continually inform my hand. My ancestor said, “from long experience I know that resemblance in a portrait is essential; but no fault shall be found with the artist, at least by the sitter, if he improve the appearance”.

NOL: How did you learn about the availability of woolly mammoth ivory?

TS: My first efforts were on Ivorine, a 20th century ivory substitute, and then vellum mounted on card. One supplier led me to another until I found someone in Dorset who could obtain mammoth ivory from Siberia where research crews have been finding whole woolly mammoths preserved in the permafrost. He has since sold his business but fortunately I have a pretty good stockpile.

Tom Sully: Eric, His Eye, 2011, watercolor on ivory, 3/4 x 5/8 in.

NOL: What led you to painting eye portraits?

TS: My interest was piqued by an article about eye portraits that I found in a 1904 issue of The Connoisseur. When a portrait commission took me to Philadelphia, I was spellbound by the collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. They are surely the most startling and, as portraits exchanged between lovers, the most romantic form of the art. There is a mystery to eye portraits that I’m unable to explain. It may come in part from seeing such an arresting image in so small a format – they are usually no bigger than one-half to three-quarters of an inch. In the Look of Love show currently at the Birmingham Museum of Art, there are stick pins and rings with images even smaller! In my experience of painting these, people that know the portrait subject immediately recognize them from this one fragment. I also find that they resonate well with a contemporary art audience. As I said to my wife one day, “eye portraits are so damn strange that they may as well be cutting-edge contemporary art!”

Tom Sully: Lucy, watercolor on ivory, 2/2 x 2 1/8 in.

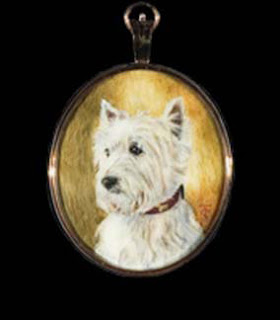

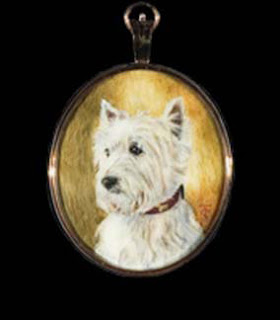

NOL: We noticed on your website that you also paint dogs.

TS: I love painting dog portraits. One need only look at the work of Sir Edwin Landseer to see that dog painting is serious business. Dogs are great to w

ork with since they are less self-conscious than we are. A British client hired me to paint miniatures of his two bulldogs. When one of them died about six months later, we realized we had been unknowingly prescient. I painted a West Highland Terrier in Palm Beach who was so poised that she must have been a fashion model in a previous life.

Tom Sully: Solomon, 2006, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 x 2 1/16 in.

NOL: What do you charge for a portrait miniature?

TS: I charge $3,000 for a head and shoulders to half-length portrait miniature and $2,500 for an eye portrait. These prices include the cost of a locket in rose gold, yellow gold or sterling silver.

NOL: Tell us about your current work?

TS: I’m currently painting an eye portrait commission for a client in Birmingham, Alabama. I’m also working on a body of Louisiana inspired landscapes for a show in New Orleans this fall. I used to live there and began exploring the countryside for landscape subjects during the evacuation from Hurricane Katrina. The bayou country and especially the swamps, which seem to exist outside of time and civilization, are a great subject for a painter with a Romantic bent.

Tom Sully: Grand Coteau Oak, 2012, oil on linen 22 x 27 in.

NOL: What are your upcoming exhibitions?

TS: Louisiana Reveries: Landscapes by Thomas Sully, October 6 – 31, 2012;

Jean Bragg Gallery of Southern Art, 600 Julia Street, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Tom Sully: Nocturne in Blue and Gold, 2011, oil on linen 24 x 18 in.

NOL: Many thanks to you, Tom Sully. Your life and work are fascinating.

Tom Sully: Night Flight, 2012, oil on linen, 17 x 24 in.