As a collector of experiences at English country homes, I longed to see Woburn Abbey, a center of Whig politics in the 18th and 19th centuries, a great house full of treasures with its grand deer park and lovely gardens. I finally realized this ambition in May of 2009, staying in the village of Woburn and touring the estate, but not the safari park (about which more later).

As you can tell from this aerial view, the estate is thousands of acres. Click here to visit WOBURN ABBEY. I wish I could have spent several more days exploring every corner, but alas, the next leg of the trip had its temptations.

Woburn Abbey, seat of the Dukes of Bedford, was the site of a Cisterian Abbey founded in the twelfth century. After he dissolved the Roman Catholic abbeys, Henry VIII gave the property to John Russell, who served as Lord Privy Seal.

The titles of Earl and Duke of Bedford have a complicated history. The titles were bestowed by the reigning monarch then lost through forfeiture or lack of issue at least six times before the 16th century. Edward VI honored John Russell, his close advisor, with the earldom of Bedford in 1551. The Russell family home remained in Cheshire until the time of the 4th Earl who began to build at Woburn in the early 17th century.

The 5th Earl was awarded a dukedom by William and Mary for his service in the Glorious Revolution. The family remained devoted Whigs throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Above, Lord John Russell (1792-1878), third son of the 6th duke, Prime Minister for two periods during the reign of Queen Victoria.

Repton followed Brown’s general scheme of undulating hills, clumps of trees, irregularly shaped lakes and meandering streams, an idyllic recreation of the natural English countryside, complete with grazing sheep and gamboling lambs. Repton often added romantic elements, such as grottoes, and themed “rooms” of contrasting garden styles. His taste for the picturesque was fully realized in Woburn’s Chinese Dairy, above.

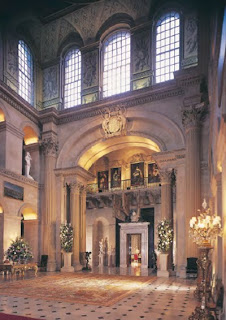

The house, once much larger than it is today, was designed by architects Henry Flitcroft and Henry Holland in the mid-18th century. In 1950, part of the house was demolished due to dry rot and the facades of the remaining wings were restored.

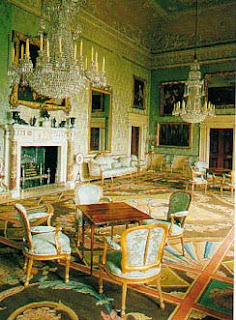

A tour of the interior is one feast for the eyes after another. Queen Victoria’s Bedroom is part of the State Apartments, used for visiting royalty, which included Elizabeth I while the house was still a monastery. Albert and Victoria came in 1841 and the Queen wrote of her enjoyment of the fine collection of pictures.

One of the most famous in the Woburn Collection is the Armada portrait of Elizabeth I, by George Gower, 1588, which celebrates the great English victory over the Spanish fleet. Many great Russell family portraits by such artists as VanDyke, Reynolds, and Gainsborough, hang throughout the rooms on public view.

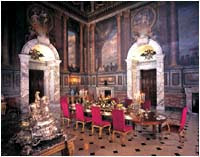

The State Dining Room, left, shows a selection of these portraits as well as the delicate Meissen dinner service adorned with birds and dating from about 1800.

Further along the house tour, another dining room contains the collection of more than twenty views of Venice by Canaletto (1697-1768), commissioned by the Fourth Duke on his Grand Tour about 1730. The view to the right is Entrance to the Arsenal.

At Covent Garden, the fourth Earl of Bedford engaged architect Inigo Jones to develop the grounds of the old convent garden. Jones designed a market place, based partly on the Place des Vosges in Paris, the kind of place we would call mixed use today, with shops, entertainment and residences. Jones also designed St. Paul’s Church, above.

At right is another of the former Russell/Bedford London holdings, Russell Square in Bloomsbury. In fact the freehold of some of this area is still held by the family. Russell Square was also designed by Humphry Repton and revitalized in the last decade.

One of my favorite aspects of visiting great country houses is to learn about the families, and the Russell/Bedford clan has a particularly delicious set of duchesses about which to write. But I must save that for a later post.

In closing, a few views from the Woburn Safari Park which not only entertains thousands of visitors but also particpates in several worldwide plans to preserve endangered wildlife. It was opened in 1970 by the 13th Duke of Bedford.