Each year, at the beginning of November, I start checking the mailbox for my invitation to spend Christmas at Stratfield Saye. Each year, I’m disappointed in this hope. All is not lost, however, as I’ve still been fortunate enough to spend a few Christmas’s, and a New Year’s Eve or two, in England anyways. Recently, Victoria and I were mulling over our choices for future holiday stays and we both thought it would be grand to really splash out and spend the hols at a stately home or three – even if none of them are Stratfield Saye.

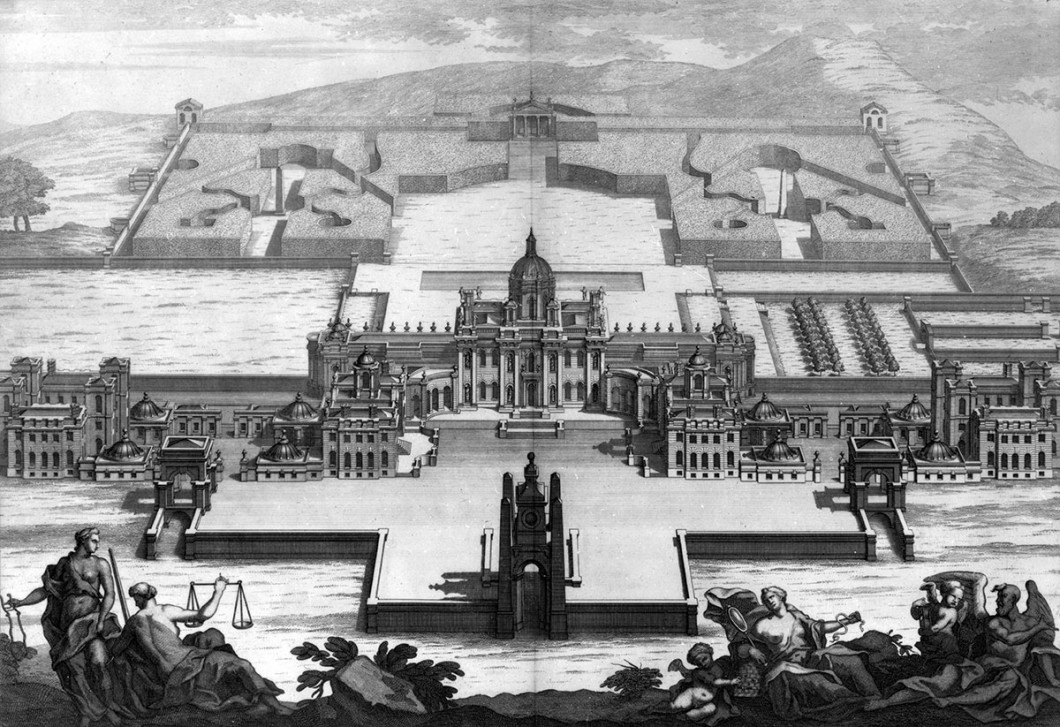

Victoria suggested Castle Howard, above, in Yorkshire, which will be decorated and receiving visitors until 22 December. From their website: “Beautifully decked out each Christmas by the Hon.Simon and Mrs Howard, a visit to Castle Howard fills the festive season with sparkle and cheer. Approach the magnificent 18th-century house along the Christmas tree-lined drive.

“Inside, discover breathtaking interiors lit by candle and firelight, dressed with magnificent trees, a stunning display of traditional Howard family ‘twigs’, winter garlands and floral arrangements. Christmas at Castle Howard includes live music performances daily, audiences with Father Christmas and delicious seasonal menus in the restaurant and cafés. Remember to leave enough time to visit the gift shops, Farm Shop and Garden Centre where you can pick up that special Christmas gift.”

Victoria also suggested Wiltshire’s Bowood House, above, for which she harbors a soft spot in her heart, not least because it’s home to the current Marquis and Marchioness of Lansdowne. Speaking of whom, here’s the invitation to visitors from the Lady of the House: “For the second year the Marchioness of Lansdowne invites you to Bowood House Christmas Extravaganza. See Bowood House decorated for a family Christmas and indulge in a fantastic shopping experience. Come and see stunning stalls filled with handmade toys, Christmas food, antiques, evening clothes, indulgences, shoes, books, silk flowers, handbags, furs, puzzles, table decorations, candles, book signing by famous food writers and much much more.” The Extravaganza has become a seasonal favorite – last year, the Duchess of Cornwall paid a visit.

While Bowood House itself closes to the public before Christmas proper, the Bowood Hotel, Spa and Golf Resort.offers a two night Christmas Break, which includes a Christmas Eve visit to Lord and Lady Lansdowne –

Two Night Christmas Break – Get away for two nights with dinner, bed and breakfast, as well as full use of our spa facilities. What the break includes:

Christmas Eve

Arrive in time for a Champagne High Tea, served between 3pm and 4pm, before heading down to Bowood House to join Lord and Lady Lansdowne for carols in the private family chapel, followed by mulled wine and mince pies in the Orangery. Return to the hotel for a delicious three course dinner. If you wish to attend midnight mass in the village church, transport will be available. Then it’s time to relax. Enjoy a nightcap or a complimentary hot chocolate before you head up to bed and remember to put your Christmas stocking on your door before you go to sleep.

Christmas Day

Start the day with a full Wiltshire Breakfast. Spend the morning relaxing or work up an appetite with a walk in the beautiful Bowood Grounds. Santa will arrive with gifts for all. Lunch will be a gourmet experience offering traditional Christmas fayre, with a menu designed and cooked by our Executive Chef. The afternoon is a time for a nap or to watch the Queen’s speech and if you’re peckish, you’ll be able to help yourself to a delicious rolling buffet in the evening.

Boxing Day

Enjoy a full Wiltshire Breakfast and then make use of the luxurious Spa facilities before you leave. If you want to postpone your departure, add an extra night bed and breakfast from only £170 per room.

From only £450 per adult, £200 per child. Prices are based on two people sharing a twin or double room, single supplement applies, upgrades are available at a supplement. Price per child is based on sharing with two adults. If two or more children, an adjoining room will be offered for £375 per child, subject to availability. For more information or to make a reservation please call Bowood Hotel Reception on 01249 822228.

Personally, I’d love to see Chatsworth House at the holidays. The Duke and Duchess of Devonshire first opened the House to visitors at Christmas as a way of making up revenues after a year of poor visitor attendance due in part to hoof and mouth disease in the local area. Now, decades on, the Chatsworth Christmas displays are a well loved tradition for visitors from near and far.

This year, from November 9 to December 23, Chatsworth offers Christmas displays on the lower

floors of the house. The theme for Christmas 2013 is ‘The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe at Chatsworth.’ In addition, each year the House hosts Christmas Market Weekends, seasonal floral workshops and twilight evenings.

The Cavendish family also own Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire and its there that you can enjoy a magical walk and discover the 12 scenes from the traditional carol come to life. Explore Strid Wood to find the 12 scenes – see 7 swans a-swimming, 3 real french hens and have a go on the drums. Nearby, the Devonshire Arms Country House Hotel and Spa offers its own fabulous Christmas Package. From their website:

With its signature puddings and wild moors, Yorkshire is a marvellously English place to spend Christmas. One of the county’s finest properties is the 30,000-acre Bolton Abbey Estate in the Dales, owned by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire; and, on it, the Devonshire Arms Country House Hotel and Spa is offering two- and three-night Christmas packages. A Champagne reception and dinner in the Michelin-starred Burlington Restaurant will warm guests up for some carol-singing,

Christmas Eve –

| Champagne Afternoon Tea, this will be served in the lounges and will include a variety of delights | |

| 19.00 | Drinks Reception in the Cocktail lounge |

| 19.30 | Seated for a set menu dinner The Burlington Restaurant. We respectfully advise that the dress code for this evening is Jacket and Tie |

| 22.30 | The Choir will leave to take their place in The Priory for Midnight Mass. We invite you to board the 1920’s Charabanc to chauffeur you to The Priory from 10.45 pm |

| 23.30 | Celebrate the First Mass of Christmas |

| 00.30 | Once safely back at the Hotel, and if you can fit it in, enjoy hot chocolate, marshmallows, brandy, mulled wine and mince pies as a bed time treat. |

| Christmas Day Breakfast is served in the Burlington Restaurant. |

|

| 10.00 | Morning mass at the Bolton Priory for those wishing to attend, The Priory is approximately 1 mile along the river or road. Reception has information on other Church services. |

| 12.30 | Champagne reception in the cocktail lounge. |

| 13.30 | The Traditional Christmas Luncheon, served in the Burlington Restaurant. |

| 16.30 | Games or walk |

| 19.00-20.00 | A Christmas buffet will be served in the Burlington. Help yourself to as much as you can eat. |

| 20.30 | Christmas Pub quiz to be held in the Brasserie. |

Boxing Day

| 8.00-10.00 | Traditional Breakfast will be served in the Burlington Restaurant. |

| 12.00 noon | Join the Airedale Beagles in the Devonshire’s front car park on their traditional Boxing Day hunt. Mulled wine & mince pies will be available to keep you warm! |

| 12.00 noon | For those of you who have chosen to go on the guided walk with Eddie, please meet in Reception at 12.00 noon, to see the Beagles & returning at approx 3.30pm to 4.00pm.Packed Lunch will be provided. |

| 12.30–14.00 | For those not attending the walk, a Boxing Day lunch is served in The Burlington Restaurant. |

| 19.00-00.00 | Champagne Reception prior to Boxing Night Black Tie Dinner with wine package and Jazz Band in the Cavendish Room, this is when the prizes will be given to those who have won the competitions. |

Three-night packages from £1,645 per room. Devonshire Arms Country House Hotel and Spa, Bolton Abbey, Skipton, North Yorkshire (01756 710441; www.thedevonshirearms.co.uk)