Oh, ice cream . . . one of the sweetest things in life. Now that the summer weather approaches, I thought it might be time for a blog on the history of the icy treat.

The first recorded serving of ice cream in England was in 1672, when King Charles II’s table at a banquet was served ‘one plate of white strawberries and one plate of iced cream.’ The first English cookery book to give a recipe for ice cream was Mrs. Mary Eales’ Receipts of 1718. Ice being rare, ice cream was a luxury reserved for the wealthy and had to be made and served immediately, there being no way to store it for any length of time.

The production of ice cream depended upon ice, which could be gathered from ponds and lakes in winter, while the use of ice houses goes back several centuries. By packing ice into an insulated underground chamber ice could be stored for months, sometimes years. In the early 19th century importation of ice started from Norway, Canada and America, this made ice cream readily available to the general public in the UK. Ice was shipped into London and other major ports and taken in canal barges down the canals, to be stored in ice houses, from where it was sold to ice cream makers. This burgeoning ice cream industry, run mainly by Italians, started the influx of workers from southern Italy and the Ticino area of Switzerland to England. In London, the huge ice house pits built near Kings Cross by Carlo Gatti in the 1850s, where he stored the ice he shipped to England from Norway, are still there and have recently been opened to the public at The London Canal Museum.

Although they had been available in England since the 1670’s, ices were popularised by French and Italian confectioners who set up shops in London and elsewhere in the 1760’s, when horticultural and pastural themes became popular as decoration for entertainments. Tables were laid in imitation of formal gardens or parks, complete with flower-beds of coloured sugar, gravel walks made from aniseeds, trees of candy and sugar paste figures. In 1765, the Duke of Gordon purchased a complete garden dessert from the Berkeley Square confectioner Domenico Negri for £25-7s-9d and served his guests at a table decorated with a brass-framed plateau adorned with Bow figures, china swans, glass fountains, parterres, a china umbrella and a kaleidoscopic display of sugar plums and bonbons. A surviving trade card advertising Negri’s shop is illustrated with fantasy temples, pagodas and fountains. Many decades later, these nature themes remained popular, with Lady Blessington having a live song bird presented at table in a spun sugar cage.

In Grantley Fitzhardinghe Berkeley’s memoirs, titled My Life and Recollections (1865), Berkeley offers the following anecdote:

On these hunting days some very amusing things happened with my hunt which I have since seen attributed to various other persons. The Gunters, the renowned pastrycooks of Berkeley Square, were all fond of hunting, were frequently out with my hounds, and subscribed to the hunt.

“Mr. Gunter,” remarked Alvanley, “that’s a fine horse you are on.”

“Mr. Gunter,” remarked Alvanley, “that’s a fine horse you are on.”

” Yes, he is, my lord,” replied Gunter, ” but he is so hot I can’t hold him.”

” Why the devil don’t you ice him, then?” rejoined his lordship.

Gunter looked as if he did not like the suggestion.

Originally, ice cream was sold on the street in glasses that were wiped clean and re-used. These glass “licks” remained in use in London until they were made illegal in 1926 for health reasons. However, the forerunners of the ice cream cone as we know it also existed. G. A. Jarrin, an Italian confectioner working in London in the nineteenth century, wrote about almond wafers that should be rolled “on pieces of wood like hollow pillars, or give them any other form you may prefer. These wafers may be made of pistachios, covered with currants and powdered with coarse sifted sugar; they are used to garnish creams; when in season, a strawberry may be put into each end, but it must be a fine” . . . He suggested turning another of his wafers into “little horns; they are excellent to ornament a cream.” Ice cream cones were also mentioned by Mrs Agnes Marshall in her book Fancy Ices of 1894.

The first ice cream bicycles in London were used by Walls in London in about 1923. Cecil Rodd of Walls came up with the slogan “Stop Me and Buy One” after his experiments with doorstep selling in London. In 1924 they expanded the business, setting up new manufacturing facilities and ordering 50 new tricycles. Sales in 1924 were £13,719, in 1927 £444,000. During the war years (1939-45) manufacture of ice cream was severely curtailed, and the tricycles requisitioned for use at military installations but in October 1947 Walls sold 3,300 tricycles and invested in freezers for it’s shops. Walls remains the market leader in the UK for individual hand-held products such as Cornetto and Magnum.

Needless to say, the craze for ice cream continues today and I’m sure that Regency folk would be amazed to find that ice cream is nowadays affordable, can be kept at home and is offered in flavors with names such as Chunky Monkey and Rum Raisin – the sweet things in life, indeed.

Give `Em The Wellie – An Introduction to Bootmaker George Hoby

George Hoby was not only the greatest and most fashionable bootmaker in London, but, in spite of the old adage, “ne sutor ultra crepidam,” he employed his spare time with considerable success as a Methodist preacher at Islington. He was said to have in his employment three hundred workmen; and he was so great a man in his own estimation that he was apt to take rather an insolent tone with his customers. He was, however, tolerated as a sort of privileged person, and his impertinence was not only overlooked, but was considered as rather a good joke. He was a pompous fellow, with a considerable vein of sarcastic humour, as evidenced in the following anecdotes handed down to us by Captain Gronow –

I remember Horace Churchill, (afterwards killed in India with the rank of major-general,) who was then an ensign in the Guards, entering Hoby’s shop in a great passion, saying that his boots were so ill made that he should never employ Hoby for the future. Hoby, putting on a pathetic cast of countenance, called to his shopman, “John, close the shutters. It is all over with us. I must shut up shop; Ensign Churchill withdraws his custom from me.” Churchill’s fury can be better imagined than described. On another occasion the late Sir John Shelley came into Hoby’s shop to complain that his topboots had split in several places. Hoby quietly said, “How did that happen, Sir John?” “Why, in walking to my stable.” “Walking to your stable!” said Hoby, with a sneer. ” I made the boots for riding, not walking.”

Hoby was bootmaker to George III, the Prince of Wales, the royal dukes, Beau Brummell, most of the aristocracy and many officers in the army and navy. His shop was situated at the top of St James’s Street, at the corner of Piccadilly, next to the old Guards Club. Hoby was the first man who drove about London in a tilbury. It was painted black, and drawn by a beautiful black cob. This vehicle was built by the inventor, Mr Tilbury, whose manufactory was in a street leading from South Audley Street into Park Street.

No doubt Mr. Hoby had patterns for all manner of desirable boots, evidenced not in the least by his impressive client list. However, he will forever be linked to a boot design not of his making. Of course I refer to the Wellington boot, a pair of the Duke’s own boots of this design are pictured at left. Hoby had been bootmaker to the Duke of Wellington from his boyhood, and received innumerable orders in the Duke’s handwriting, both from the Peninsula and France, which he always religiously preserved. The Duke asked Hoby to modify the 18th-century Hessian boot to a height below the knee, in order to make them more practical for walking and riding. The resulting boot was made of softer calfskin leather, had no trim, boasted heels one inch high and fit more closely around the leg, making it more practical and hard-wearing for battle, yet comfortable for the evening. The boot was dubbed the Wellington and was quickly adopted by Hoby’s other customers.

Hoby was also bootmaker to the Duke of Kent; and as he was calling on H.R.H. to try on some boots, the news arrived that Lord Wellington had gained a great victory over the French army at Vittoria. The duke was kind enough to mention the glorious news to Hoby, who coolly said, “If Lord Wellington had had any other bootmaker than myself, he never would have had his great and constant successes; for my boots and prayers bring his lordship out of all his difficulties.”

Hoby may have had a penchant for sarcasm and a high opinion of himself (and his own influence upon British military history) but he knew how to run a business – Hoby died worth a hundred and twenty thousand pounds.

DO YOU KNOW ABOUT: JAMES LEES-MILNE?

As some of you may already know, I am a great reader of British diaries, letters and journals. There are many such volumes on the shelves of my personal library. From Pepys to Queen Victoria, I adore the immediacy of these personal writings, the way they drop you right into the lives of their authors and introduce you in a very intimate manner to people, places and times otherwise vanished. Recently, I came across the diaries of James Lees-Milne, which had somehow managed to escape my notice over the past few decades. JML was in at the very beginnings of the National Trust and the Georgian Society, amongst other things, and was advisor to the National Trust on which properties should be purchased and preserved by that body. In this capacity, JML travelled around the UK, poking his nose into a variety of stately homes and writing down for posterity his views on their architectural merits, their contents and their owners, often with wit and sometimes with chagrin, but always in a way that can’t help but to amuse the reader. In addition, JML lived in London and spent much of the 1930’s and 1940’s mixing with the Bright Young Things, various celebrities and writers and members of the Royal Family. No doubt you’ll appreciate that all of this makes for great fodder in the diary of someone who had a keen observational eye and a talent for first person prose. To read more about the accomplishments of James Lees-Milne, you will find the 1997 obituary that ran in The Independent here.

You’ll understand when I tell you that I was prepared to like these Diaries before I’d read Page 1, but I wasn’t prepared to find that so many of the entries would resonate with me on a personal level.

Tuesday, 17th February, 1942

Dined with Harold Nicolson and Jamesey at Rules. We talked about Byron’s sex life . . . .

Do you mean to say that other people sit around various London venues discussing the sex lives of dead people? Granted, in my circle we tend to focus on Brummell’s sex life, but close enough, what? And then there’s this entry –

Wednesday, 13th October, 1948

This evening I dined with the John Wyndhams. . . . After dinner, when the women left, talk was about how little we know of the everyday life of our ancestors in spite of George Trevalyan’s history. Jock Colville suggested we ought to go home tonight and write down in minute detail how we drove to the Wyndham’s door, left our car at the kerb, its doors firmly locked, rang the bell, were kept waiting on the doorstep, how we were received by a butler wearing black bow tie instead of white, what the hall smelt like, how the man took our coats and hats, putting them on a chest downstairs, and how he preceded us upstairs, one step at a time, etc., etc.

Positively uncanny. How often have myself and my friends, many of whom are writers of historical novels, lamented this very same thing and had almost the exact same discussion? By this time I was finding the diaries so delicious that I had to call Victoria immediately.

“Hello.”

“Have you ever heard of James Lees-Milne? You must start reading him now. He’s our new best friend. Where has he been all of our lives? How could either of us not known about his existence before now?”

“Who?”

“James Lees-Milne. The National Trust guy. Friends with everyone, including the Mitfords. He and his friends used to sit around discussing Byron’s sex life.”

“James who?”

“Hang up. I’m emailing you the link to his Diaries now. On Kindle. Buy them.”

Of course, not all of the Diary entries are about such musings. As I’ve said, JML lived in London during this period and there is much to be found about the City, especially during wartime. Again, they resonated with me because much of JML’s London incorporates my London, i.e. the areas and places in London that I revisit and in which I feel most at home.

Thursday, 24th February, 1944

There is no doubt our nerves are beginning to be frayed. Frank telephoned this morning. I could tell by his voice he was upset. He said he was going to leave the Paddington area and thought Chelsea or Belgravia would be safer. I said I doubted whether the Germans discriminated to that extent. This evening I went to see a crater in the road, now sealed off, in front of St. James’s Palace. The Palace front sadly knocked about, the clock awry, the windows gaping, and shrapnel marks on the walls. A twisted car in the middle of the road. . . In King Street Willis’s Rooms (Almack’s) finally destroyed, one half having gone in the raid of (May) 1941 when I was sheltering in the Piccadilly Hotel.

Sunday, 18th June, 1944

At Mass at 11 there was a great noise of gunfire and a rocket. In the afternoon Stuart walked in and said that a rocket had landed on the Guards’ Chapel (Wellington Barracks) during service this morning, totally demolishing it and killing enormous numbers of Guards officers and men. Now this did shake me. After dining at the Churchill Club we walked through Queen Anne’s Gate, where a lot of windows with the old crinkly brown glass panes have been broken. In St. James’s Park crowds of people were looking at the Guard’s Chapel across Birdcage Walk, now roped off. I could see nothing but gaunt walls standing, and gaping windows. No roof at all. While I watched four stretcher-bearers carried a body under a blanket, a (air raid) siren went, and everyone scattered. I felt suddenly sick. Then a rage of fury against the war raged inside me. For sheer damnable devilry what could be worse than this terrible instrument?

To think that Gunter’s and Almack’s had managed to survive until the War. In fact, JML was a patron of Gunter’s –

Saturday, 16th June, 1945

This morning the telephone man came to Alexander Place to say he would install my telephone on Monday . . . the bath however is still unattached to the pipes. The house painter and I picnic together. I leave the house each morning at 7.30 to bathe, shave and breakfast at Brooks’s, where I virtually live. In Heywood’s shop I met Diana (nee Mitford) Mosley and Evelyn Waugh with Nancy (Mitford). I kissed Diana who said the last time we met was when I stayed the night in Wootton Lodge, and we both wept when Edward VIII made his abdication broadcast. I remember it well, and Diana speaking in eggy-peggy to Tom Mosley over the telephone so as not to be overheard. . . . We all lunched together at Gunter’s. . . .

|

| Brooks’s Club, St. James’s Street |

Lees-Milne stirs the heartstrings of every Anglophile with this entry –

Saturday, 17th June, 1944

Worked in Brooks’s library this afternoon. I am always happy in this stuffy, dingy Victorian library, in which the silence is accentuated by the relentless ticking of the old, stuffy clock.. I love the old stuffy books on the stuffy brown shelves, books which nobody reads except Eddie Marsh, and he falls fast asleep over them. The very atmosphere is calculated to send one asleep, but into the gentlest, most happy, nostalgic dreams of ninetheenth-century stability, self-satisfaction and promise of an eternity of heavenly stuffiness, world without end. How much I adore this library, and club, nobody knows. May it survive Hitler, Stalin and all the beastliness which besets us.

As I said, JML travelled the length and breadth of the UK both for his National Trust work and in order to visit various friends and relations. His entries concerning the Duke of Wellington were of particular interest, especially as they illustrate the consequences which the burden of caring for the first Duke’s belongings could bring about –

Saturday, 15th April, 1944

I caught the 1.15 to Reading where Gerry Wellington met me at the station in his small car, for he gets twenty gallons a month for being a duke. . . the western front of Stratfied Saye house clearly shows it to date from Charles I’s reign . . . . the east front is not so regular as the west, and the terraces are deformed by messy Edwardian flower beds. Gerry, who hates flowers, will soon have them away . . . Having eaten little luncheon I was famished, but tea consisted of only a few of the thinnest slices of bread and butter imaginable. After tea we did a tour of the inside of the house, beginning with the hall. When my stomach started to rumble with hunger Gerry looked at it with a reproachful air, and said nothing. It went on making the most awful noise like a horse’s. The hall has a gallery along the wall opposite the entrance. The open balusters were boxed in so as to prevent the servants being seen from below by the visitors. Gerry’s mother used to say that nothing of them was visible except their behinds, as they crouched and bobbed across the gallery. . . . the dining room is shut up, all the Apsley House pictures being stored there for the war, and valued at a million pounds, so G. says. . . . After dinner, at which there were no drinks except beer, (Gerry) showed me his grandfather’s collection of gems and intaglios, mounted on long, gold chains. When held against the oil lights, some of the stones were very beautiful. G. is very fussy over the key bunches, everything being carefully locked up. He has a butler, cook and two housemaids, and a secretary, Miss Jones. The last has meals with him during the week, and nearly drives him mad with her archness. `Aren’t you naughty today?’ she says. She is unable to type, so when he wishes to dispatch a letter not written by himself, he types it and gives it to her to sign.

|

| Gerald Wellesley, 7th Duke of Welligton |

and

Sunday, 26th June, 1948 (at Stratfield Saye)

Lady Hudson and Lady Granville came to tea, and Lady G. suddenly developed St. Vitus’s dance and jangled the cup in her saucer, spilling scalding tea through a thin silk dress on to her knees, and smashing the saucer to smithereens. Gerry leapt up, seized the table upon which a few drops of the tea had sprinkled and rushed away with it to have the surface polished. He made not a gesture of help or sympathy to poor Lady Granville who was in considerable pain and distress. Typical Gerry behaviour. He never lets one down. His patent anxieties about his possessions bring these catastrophes about . . . . .

Below are just three more examples of JML’s entries on stately homes that afford us an insight onto a bygone way of life –

Thursday, 4th May, 1944

Martineau and I lunched at the Hyde Park Hotel with Lord Braybrooke, who has recently succeeded two cousins (killed on active service), inheriting the title and Audley End (House, Essex). He is a bald, common-sensical, very nice business man of 45, embarrassed by his inheritance. At his wit’s end what to do with Audley End. Who wouldn’t be? It was arranged that Martineau and I would visit the house with him in June. It is requisitioned by the Army and used for highly secret purposes, so that even he is not allowed into the rooms except in the company of a senior officer. Consequently he hardly knows the way round his own house. . . .

Saturday, 25th August, 1945

Describing a journey to Birr Castle – I woke at 5.45 and at 6.45 the car ordered by Michael Rosse called for me. It picked him up in Mount Street and drove us to Euston for the 8.15 to Holyhead. Travelled in comfort and ease. . . . After a smooth crossing we reached Kingstown at 7.30. I was at once struck by the old-fashioned air of everythng: horse-cabs on the quay, cobbled streets with delicious horse-droppings on them. Met by a taxi come all the way from Birr, for 8 pounds. Letter of greeting from Anne to Michael. Vodka for Michael and me in the car. We drove straight through Birr. Even through the closed windows of the car I caught the sweet smell of peat in the air. Curious scenes, ragged children on horses drawing old carts along country lanes. Our driver sounded his horn loudly through Birr, that pretty, piercing foreign horn. The gates of the castle shop open as if by magic. A group of people were clustered outside the gate. We swept up the drive. All the castle windows were alight, and there on the sweep was a large crowd of employeees and tenants gathered to welcome Michael home from the war. Anne, the two Parsons boys and Mr. Garvie the agent on the steps. Behind them Leavy the butler, the footman, housekeeper, and six or seven maids. A fire blazing in the library and everywhere immense vases of flowers. We heard Michael make a short speech from the steps, followed by cheers and `For he’s a jolly good fellow,’ a song which always makes me go hot and cold, mostly hot. The crowd then trooped off to a beano and drinks, while we sat down to a huge champagne supper at 11 o’clock.

Sunday, 1st August, 1948

Debo and Andrew (Hartington)(later 11th Duke and Duchess of Devonshire) drove me to Chatsworth this morning. The site of the house, the surroundings unsurpassed. The grass emerald green as in Ireland. The Derwent river, although so far below the house, which it reflects, seems to dominate it. Black and white cattle in great herds. . . . We wandered through the gardens, greyhounds streaming across the lawns. Andrew turned on the fountain from the willow tree. Water not only drips from the tree but jets from nozzles all round. The cascade not working this morning, but will be turned on for the public this afternoon. At present the great house is empty, under covers and dustsheets. Next year the state rooms are to be shown . . . As a couple the Hartingtons seem perfection – both young, handsome, and inspired to accomplish great things . . . Both full of faith in themselves and their responsibilities. She has all the Mitford virtues and none of the profanity. I admire them very much.

The Diaries are full of entries that shed light on the many facets to Lees-Milne’s personality, from the profound –

Wednesday, 30th November, 1949 (upon the death of his father after a long illness)

The very worst thing about death are the disprespect, the vulgarity, the meanness. God should have arranged for dying people to disintegrate and disappear like a puff of smoke into the air. There are many other scraps of advice I could have given him.

to the stingingly comic –

Sunday, 14th November, 1948

Newman, the hall porter at Brooks’s, told me I would be surprised if I knew which members, to his knowledge, stole newspapers out of the Club. I said, `You must not tell me,’ so he promptly did.

I urge you, as I urged Victoria, to waste no time in securing yourself a copy of James Lees-Milne’s Diaries. Victoria, I’m pleased to say, took my advice and read the Diaries – she loved them, too. Do let me know what you think when you’re finished with them.

THE WELLINGTON CONNECTION: MADAME TUSSAUD

|

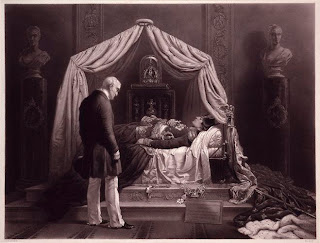

| The Duke of Wellington visiting the Effigy and Personal Relics of Napoleon at Madame Tussaud’s by James Scott, after Sir George Hayter – National Portrait Gallery Generally speaking, when one thinks about the Duke of Wellington, one seldom thinks of him in connection with trivial amusements. Rather, the formidable soldier and stern politician come to mind. However, the Duke was occasionally up for a jolly time and he had a great interest in new inventions and various amusements of the day. When the Great Exhibition of 1851 opened, the Duke went to see it nearly every day. In Struggles and Triumphs: or, Forty Years’ Recollections of P. T. Barnum by Phineas Taylor Barnum (1871), Mr. Barnum relates the following anecdote about the Duke: “On my first return visit to America from Europe, I engaged Mr. Faber, an elderly and ingenious German, who had constructed an automaton speaker. It was of life-size, and when worked with keys similar to those of a piano, it really articulated words and sentences with surprising distinctness. My agent exhibited it for several months in Egyptian Hall, London, and also in the provinces. This was a marvellous piece of mechanism, though for some unaccountable reason it did not prove a success. The Duke of Wellington visited it several times, and at first he thought that the `voice’ proceeded from the exhibitor, whom he assumed to be a skillful ventriloquist. He was asked to touch the keys with his own fingers, and after some instruction in the method of operating, he was able to make the machine speak, not only in English but also in German, with which language the Duke seemed familiar. Thereafter, he entered his name on the exhibitor’s autograph book, and certified that the `Automaton Speaker’ was an extraordinary production of mechanical genius.” The Duke of Wellington was also a great fan of Madame Tussaud’s and visited her waxworks often to see the exhibits and/or to take tea with Madame herself. He left standing instructions that he was to be told whenever a new addition to the rooms was installed. As executor of the will of George IV, Wellington was responsible for giving Madame Tussaud the monarch’s coronation robes for her exhibit. Surprisingly, the Duke’s favorite exhibit at the Wax Work was that of Napoleon. From a contemporary book titled The Curiosities of London, we learn that Madame Tussaud’s Napoleon exhibit contained the following: “Napoleon Relics. — The camp-bedstead on which Napoleon died; the counterpane stained with his blood. Cloak worn at Marengo. Three eagles taken at Waterloo. Cradle of the King of Rome. Bronze posthumous cast of Napoleon, and hat worn by him. Whole-length portrait of the Emperor, from Fontainebleau; Marie Louis and Josephine, and other portraits of the Bonaparte family. Bust of Napoleon, by Canon. Isabey’s portrait Table of the Marshals. Napoleon’s three carriages: two from Waterloo, and a landau from St. Helena. His garden chair and drawing-room chair. “The flag of Elba.” Napoleon’s sword, diamond, tooth-brush, and table-knife; dessert knife, fork, and spoons; coffee-cup; a piece of willow-tree from St. Helena; shoe-sock and handkerchiefs, shirt, &c. Model figure of Napoleon in the clothes he wore at Longwood; and porcelain dessert-service used by him. Napoleon’s hair and tooth, etc.” As to Wellington’s visits to the Exhibit, we have the following passage from The History Of Madame Tussaud’s ( Originally Published 1920 ) –

Early one morning, soon after the Exhibition had been opened for the day, Joseph, Madame Tussaud’s son, who had been wandering through the rooms, as was his habit, perceived an elderly gentleman in front of the tableau representing the lying-in-state of Napoleon I. The model of the dead exile rested—as it does down to this very day—on the camp bedstead used by Napoleon at St. Helena, and was dressed in the favourite green uniform, the cloak worn at Marengo (bequeathed by Napoleon to his son) lying across the feet. In the hands, crossed upon the chest, was a crucifix. In those days it was the custom to lower at night the curtains that enclosed the bed, in order to exclude the dust, whereas now the whole scene is encased in glass.

Observing that the visitor was desirous of seeing the effigy, and no attendant being at hand, Joseph Tussaud raised the hangings, whereupon the visitor removed his hat, and, to his great surprise, Joseph saw that he was face to face with none other than the great Duke of Wellington himself.

There stood his Grace, contemplating with feelings of mixed emotions the strange and suggestive scene before him. On the camp bed lay the mere presentment of the man who, seven-and-thirty years before, had given him so much trouble to subdue. No feeling of triumph passed through the conqueror’s mind as he looked upon the poor waxen image, too true in its aspect of death; he rather thought upon the vanity of earthly triumphs, of the levelling hand of time, and how soon he, like his great contemporary, might be stretched upon his own bier.

Mr. Joseph Tussaud used frequently to recall this dramatic meeting between the Iron Duke and the effigy of his erstwhile foe, and to imagine the feelings of the old General as he gazed upon the couch. It was probably the first of the Duke’s many visits to the Exhibition. A few days after this most interesting visit Mr. Tussaud, who was an old friend of Sir George Hayter, related the incident to that artist. Hayter was immediately struck with the potential value of the event for the production of a painting of the historic scene, and the Tussaud brothers at once commissioned him to execute the work for them. Sir George thereupon communicated the idea to the Duke, who readily responded, and offered to give the necessary sittings. We have the sketches made by Hayter in preparation for the work, and among them appears a drawing of Joseph Tussaud himself, although he does not enter the actual picture. Hearing that the artist was making progress with the painting, the Duke visited his studio, and, having expressed himself warmly in appreciation of the picture (the figures had been but lightly limned in at the time), said: “Well, I suppose you’ll want me to sit for my picture here?”

Hayter has given us a most characteristic portrait of Wellington as he then appeared. He is dressed in his usual blue frock-coat, white trousers, and white cravat, fastened with the familiar steel buckle. He stoops a little as was his wont, his head is lightly covered with snow-white hair, and his manly features are marked with an expression of mingled curiosity and sadness as, hat in hand, he looks upon the recumbent Napoleon. The picture was completed early in December, 1852, and has been on view in the Napoleon Rooms at the Exhibition ever since.

The engravings of the picture have been circulated in thousands throughout the world, and, strange to say, they are exceedingly popular in Austria. It is an interesting fact that the painting in question was the last portrait for which the Duke ever sat. When the Duke himself died, Madame Tussaud’s advertised “A full length model of the Great Duke, taken from Life during his frequent visits to the Napoleon Relics.” Wellington himself would have been least surprised to learn that Madame Tussaud had added his likeness to her collection upon his death. Unfortunately, I’ve yet to find an engraving of the Duke’s tableaux, but we do have the following description found in Our Young Folks: An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls, Volume 8 (1872) By John Townsend Trowbridge: “In a side room adjoining the long gallery lies the great Duke of Wellington in state. An awful feeling came over me, as if I were in the presence of the dead, as I looked upon that noble form, lying still and cold, with all the “pride of heraldry and pomp of power” around him, insensible alike to both. As he lay there on his tented couch of velvet and gold, it seemed as if that must be the “Great Duke,” and not a waxen image only, that never lived nor spoke. Among the numerous portraits which adorn the walls is a very fine one of the duke visiting the relics of Napoleon, which are shown in another room.” Many a person has recorded his or her feelings about the Duke of Wellington’s funeral carriage, above, a great monstrosity of a thing weighing 18 tons and made from the French guns taken in battle and designed by Prince Albert himself in a misguided attempt to pay a fitting tribute to the Duke. All agree that it was pretty much a hideous object. Charles Dickens wrote, “For form of ugliness, horrible combination of colour, hideous motion, and general failure, there never was such a work achieved as the Car.” After the funeral, there was a general debate as to what to do with the thing. The question even made its way to Parliament, as mentioned in a book called Stray Papers, published in 1876 – During a Parliamentary debate, Mr. Layard said, that there was a hideous piece of upholstery under cover opposite Marlborough House at the disposal of anybody who would take it; but, as nobody would take it, they were now asked to vote £840 for its removal to St. Paul’s, where it would be placed beneath one of the crypts. He alluded to the car used at the funeral of the late Duke of Wellington, and that which nothing more hideous had ever been invented. The best thing would be to give it to Madame Tussaud, or, if she would not take it, to burn it. The carriage now rests at Stratfield Saye. But, the same book goes on to tell us that: Several years ago, a figure of the late Duke of Wellington stood under one of the skylights in the principal room (at Madame Tussaud’s.) By some unaccountable oversight, the attendant omitted to draw the blinds on one occasion when shutting up for the night, and next morning the hot rays of a July sun fell on the Duke’s countenance with such fervour that his Grace’s nose began to run, and, by the time the doors were opened, had disappeared completely. So much of the figure being destroyed, restoration to its original form was found to be impossible. There used to be a figure of the Duke of Wellington, and Napoleon, on display at Madame Tussaud’s in London, but when I was there recently I didn’t see it. Then again, the place was so crowded I might have missed it. It’s good to think that the Duke is still around, even in storage, and might be brought out again soon. Since this post was originally published several years ago, Geri Walton has written an excellent blog post on Madame Tussaud’s Napoleon Relics. You’ll find it here.

|

THE ECCENTRIC LADY CORK

In our ongoing effort to bring to light some of the most unique ladies England has ever produced, we now introduce you to Lady Cork, about whom there appeared a story in the July – December 1903 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine:

In our ongoing effort to bring to light some of the most unique ladies England has ever produced, we now introduce you to Lady Cork, about whom there appeared a story in the July – December 1903 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine:

AN ECCENTRIC LEADER OF SOCIETY

“THERE are some women who are born for society. It is quite impossible for them to lead a quiet domestic life; excitement is as the breath of their nostrils, they must alway be agitating something, or organizing something, so as to be before the public gaze. In their youth they exhibit themselves, in middle life they exhibit other people, and act as show-women to celebrities of all kinds. Such a woman was the Hon. Maria Monckton, afterwards Countess of Cork and Orrery, who was compared by the great wit, Luttrell, to a shuttlecock, `all cork and feathers.’ Even in her girlhood she was a leader of society, and at her mother’s (Lady Galway’s) house in Charles Street, Berkeley Square, she received Johnson, Goldsmith, Burke, and all the wits of the day. She belonged to Mrs. Montagu’s Blue-stocking Club, and was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, in a garden, with a dog at her feet.”

It seems that the future Lady Cork’s appearances at balls and masquerades were often mentioned in the press of the day. In the month of February, 1770, when the Wilkes riots were going on, a certain Mrs. Comely gave a masquerade at her house, in Soho, and among the motley crew Miss Monckton was prominent, as an Indian Sultana “in a robe of cloth of gold and a rich veil. The seams of her habit were embroidered with precious stones, and she had a magnificent cluster of diamonds on her head. Her jewels on this occasion were valued at 30,000/. and she was attended by four black female slaves.”

Strangely enough, in the Daily Advertiser of the same year, but of a later date (May 7th), a mysterious paragraph appeared announcing that a ” lady of high degree would appear at the Soho Masquerade as an Indian Princess, with pearls and diamonds to the price of £ 100,000, her train to be supported by three black female slaves, and a canopy to be held over her head by four black male slaves. To be a fine sight.” Whether this paragraph was in ridicule of Miss Monckton, or put in by some one desirous of emulating her, does not appear.

At this time she was twenty-three, for she was born in 1747. She was generally known as Johnson’s ” little dunce.” Boswell relates how she came by this name. He says that Johnson “did not think himself too grave even for the lively Miss Monckton, who used to have the finest bit of blue at the house of her mother, Lady Galway.” Her vivacity enchanted the sage, they used to talk together with all imaginable ease. One evening, she insisted that some of Sterne’s writings were very pathetic. Johnson bluntly denied it. “I am sure,” she said,” they have affected me.” “Why,” said Johnson, smiling and rolling himself about, “that is because, dearest, you are a dunce!”

That was supposed to settle the question, but few people would not now allow that Miss Monckton was right, and that the sapient doctor was wrong. When she mentioned his speech to him afterwards, he replied, “Madam, if I had thought so, I certainly should not have said it.” But, all the same, the name “little dunce ” stuck to her.

That was supposed to settle the question, but few people would not now allow that Miss Monckton was right, and that the sapient doctor was wrong. When she mentioned his speech to him afterwards, he replied, “Madam, if I had thought so, I certainly should not have said it.” But, all the same, the name “little dunce ” stuck to her.It was at Brighton, or Brighthelmstone, as it was then called, that Fanny Burney (at left) first made Miss Monckton’s acquaintance. In her diary for November 10, 1782, Burney notes that the day brings in a new person, the Hon. Miss Monckton, “who is here with her mother, the Dowager Lady Galway. She is one of those who stand foremost in collecting all extraordinary and curious people to her London conversaziones, which, like those of Mrs. Vesey, mix the rank and literature and exclude all beside.”

Miss Monckton, who had sent messages as to her desire to meet Mrs. Thrale and the author of “Evelina,” at length paid her visit, and is thus described by Fanny Burney’s lively and graphic pen : “Miss Monckton is between thirty and forty, very short, very fat, but handsome, splendidly and fantastically dressed, rouged, but not unbecomingly so, yet evidently and palpably desirous of gaining notice and admiration. She has an easy levity in her air, manner, and discourse, that speak all within to be comfortable, and her rage of seeing anything curious may be satisfied, if she pleases, by looking in a mirror.”

Miss Monckton, with all her oddities, must have been very good company—she was full of brightness and “go,” she had been at the court of Marie Antoinette, and did not know the meaning of the word stiffness. When Fanny Burney returned to London she went with the Thrales to a conversazione at the “noble house” in Charles Street, and relates her experiences in her own inimitable way :

” There was not much company, for we were very early. Lady Galway sat at the side of the fire, and received nobody. She seems very old, and was dressed with a little white round cap, and not a single hair, no cushion, roll, nor anything else but the little round cap, which was flat on her forehead. Such part of the company as already knew her made their compliments to her where she sat, and the rest were never taken up to her, but belonged solely to Miss Monckton, whose own manner of receiving her guests was scarce more laborious, for she kept her seat when they entered, and only turned round her head to nod it, and say ‘How do you do ?’ As soon, however, as she perceived Mrs. and Miss Thrale, she rose to welcome them, contrary to her usual custom, merely because it was their first visit. . . . ”

Miss Burney continues by saying that the company were dressed with more brilliancy than at any rout she was ever at, as most of them were going on to the Duchess of Cumberland’s.

“At the sound of Burke’s voice, Miss Monckton started up, and cried out, ‘ Oh, it’s Mr. Burke!’ and she ran to him with as much joy as, if it had been in our house, I should. Cause the second for liking her better.” Many stately compliments were paid to Miss Burney by Burke on the subject of her novel “Cecilia,” which had just been published, and she was lionised and stared at by all the fashionable guests. Finally, Sir Joshua Reynolds wanted to see her home, and Miss Monckton pressed her to come to another conversazione, when she would meet Mrs. Siddons. This invitation was duly accepted, but after that we hear no more of Miss Monckton, who, two years afterwards, in May 1786, married Edmund, seventh Earl of Cork and Orrery. His first marriage had been dissolved in 1782, and caused much scandal to the censorious public. He only survived his second marriage with Miss Monckton twelve years, dying in November, 1798.

From her widowhood dates a new period of Lady Cork’s sway as leader of society; her house, which had been the rallying-place for all the old wits, was now thrown open to the rising stars, and her salons were crowded by all the celebrities of the Regency, and even up to the early Victorian epoch.

She always signed herself “M. Cork and Orrery.” Some furniture in the window of an upholsterer having chanced to catch her eye, she wrote to him to send it to her, signing herself as usual. His answer was: “D. B. not having any dealings with ‘M. Cork and Orrery, begs to have a more explicit order, finding that the house is not known in the trade.”

Her craze for producing oddities at her parties was so great that hearing that the celebrated surgeon, Sir Anthony Carlisle, had dissected and preserved the female dwarf, Cochinie, she was immediately seized with a desire to exhibit the curiosity at one of her assemblies, and eagerly inquired, “Would it do for a lion for tonight?”—”I think, hardly,” was the answer.—”But surely it would if it is in spirits.” The term “Lion” was used for every human set piece Lady Cork meant to present at her evening entertainments. Off posted Lady Cork to Sir Anthony’s house. He was not at home, and the following conversation passed between Lady Cork and the servant.

Servant: “There’s no child here, madam.” Lady Cork: ” But I mean the child in the bottle.” Servant: “Oh, this is not the place where we bottle the children, madam, that’s at the master’s workshop.”

Lady Cork was thoroughly modern in her way of arranging her rooms at her house in New Burlington Street. A brilliant boudoir terminated in a sombre conservatory, where eternal twilight fell on fountains of rose water, “that never dry, and on beds of flowers that never fade.” Lady Clementina Davies says that “this boudoir was literally filled with flowers and large looking-glasses, which reached from the top to the bottom. At the base was a brass railing, within which were flowers, which had a very pretty effect.”

Lady Cork was very fond of wearing white—her favourite outdoor costume was a white crape cottage bonnet and a white satin shawl, trimmed with the finest point lace. She was never seen in a cap, though she lived to be over ninety. Her complexion was wonderfully pink and white, not put on, but her own, though this does not agree with Fanny Burney’s account, which describes her as being rouged, even in her comparatively youthful days. Talking of her conversaziones, she used to say:

” My dear, I have pink for the exclusives, blue for the literary, grey for the religious, at which Kitty Bermingham, the saint, presides. I have them all in their turns; then I have one party of all sorts, but I have no colour for it.”

We have already seen how Fanny Burney in the zenith of her fame was received by Miss Monckton. Now another authoress, Lady Morgan, gives, in her “Book of the Boudoir,” a very amusing account of how she was made a lioness of by Lady Cork. On this momentous evening she was only Sydney Owenson, just beginning to come into public notice as the authoress of “The Wild Irish Girl.” She relates how she ascended the marble staircase, with its gilt balustrades, her heart beating all the while with trepidation. She was wearing the same white muslin frock and flower that she had worn some nights before when she was dancing jigs with the Prince of Breffni in a remote corner of Ireland. Her black curly hair was, as usual, cut in a crop, and her brilliant black eyes shone with even more than their accustomed lustre.

She was met at the door by Lady Cork, all kindness and anxiety to show her off to the company. The whole description is so inimitable that it is best to give it in Lady Morgan’s own words :

“‘ What! No harp, Glorvina ?’ said her ladyship.

‘”Oh, Lady Cork!’

“‘ Oh, Lady Fiddlestick, you are a fool, child—you don’t know your own interests. Here, James, William, Thomas, send one of the chairmen to Stanhope Street, for Miss Owenson’s harp !’

“Led on by Dr. Johnson’s celebrated little dunce,” says ‘ The Wild Irish Girl,’ “I was at once merged in that crowd of elegants and gallants.” (Among the crowd, by the way, was a strikingly sullen-looking handsome creature, the soon-to-be celebrated Lord Byron.) “I found myself suddenly pounced down upon a sort of rustic seat by Lady Cork. … So there I sat, the lioness of the evening, exhibited and shown like the beautiful hyena that never was tamed, looking about as wild, and feeling quite as savage. Presenting me to each and all of the splendid crowd which an idle curiosity had gathered round us, Lady Cork prefaced every introduction with a little exordium,’ Lord Erskine, this is the ‘Wild Irish Girl,’ whom you are so anxious to know; I assure you she talks quite as well as she writes. Now, my dear, do tell Lord Erskine some of those Irish stories that you told the other evening at Lady Charleville’s. Fancy yourself en petit comiti, and take off the Irish brogue. Mrs. Abington says you would make a famous actress, she does indeed. This is the Duchess of St. Albans— she has your ‘Wild Irish Girl’ by heart. Where is Sheridan? Do, my dear Mr. T. (this is Mr. T., my dear, geniuses should know each other), do, my dear Mr. T., find me Mr. Sheridan. Oh, here he is. What! you know each other already ? Tant mieux. Mr. Lewis, do come forward. This is Monk Lewis, my dear, of whom you have heard so much, but you must not read his works, they are very naughty. . . . Do see, somebody, if Mr. Kemble and Mrs. Siddons are come yet! And pray tell us the scene at the Irish baronet’s in the rebellion, that you told the Ladies of Llangollen. . . . And then give us your bluestocking dinner at Sir R. Phillips’s, and describe us the Irish priests. . . .'”

Towards the end of the evening, Kemble did appear, and his remark to the Irish siren was, “Little girl, where did you buy your wig?” Being assured that her hair grew on her head, he next drew forth a copy of “The Wild Irish Girl ” from his pocket, and asked the little authoress why she wrote such nonsense, and where she got all the hard words? She promptly replied, “Out of Johnson’s dictionary.” Her epitome of the evening was as follows : “I can only say that this engouement (she means Lady Cork’s passion for exhibiting lions), indulged perhaps a little too much at my expense, has been followed up by nearly twenty years of unswerving kindness and hospitality.”

Mrs. Opie relates how she went to an assembly at Lady Cork’s in June 1814, at which Blucher, the Prussian general, then one of the lions of London society, was expected. The company, which included Lord Limerick, Lord and Lady Carysfort, James Smith of the ” Rejected Addresses,” and Monk Lewis, waited and waited, but no Blucher appeared. To keep up Lady Cork’s spirits, Lady Caroline proposed acting a proverb, but it ended in acting a French word, orage. She, Lady Cork, and Miss White went out of the room and came back digging with poker and tongs. They dug for or (gold), they acted a passion for rage, and then they acted a storm for the whole word, orage. Still, the old general did not come, and Lady Caroline disappeared, but presently Mrs. Wellesley Pole and her daughter arrived, bringing with them a beautiful Prince—Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg (afterwards married to the Princess Charlotte), but saying that she feared Blucher would not come. “However,” continues Mrs. Opie, “we now heard a distant, then a near hurrah, the hurrahs increased, and we all jumped up saying, ‘There’s Blucher at last!’ The door opened, the servant calling out, ‘General Blucher!’ on which in strutted Lady Caroline Lamb (at left) in a cocked hat and great coat.”

Lady Cork’s house in New Burlington Street was most tastefully fitted for the reception of her illustrious guests: every part of it abounded in pretty things—objets, as they are sometimes called, which her visitors were strictly forbidden to touch. Beyond her magnificent drawing-rooms appeared a boudoir, and beyond it a long rustic room, with a moss-covered floor, with plants and statues; while the lower part of the house consisted of a handsome dining-room and library, which looked upon a small ornamented garden, where a fountain played; beyond these were a couple of rooms fitted up like conservatories, in which she received her guests before dinner.

Lady Cork was fond of showering expensive presents on those she liked. Mrs. Opie says, “Lady Cork has given me a most beautiful trimming for the bottom of a dress, which I am to wear on the 4th. It is really handsome, a wreath of white satin flowers worked upon net.” In addition, she could be generous to her friends in other ways. ” In 1780, the year of a general election, Sheridan’s (right) object was to get into Parliament if possible, and he was going to make a trial at Wootton-Bassett. The night before he set out, being at Devonshire House and everybody talking about the general election, Lady Cork asked Sheridan about his plans, which led to her saying that she had often heard her brother Monckton say he thought an opposition man might come in for Stafford, and that if, in the event of Sheridan failing at Wootton, he liked to try his chance at Stafford, she would give him a letter of introduction to her brother. This was immediately done. Sheridan went to Wootton-Bassett, where he had not a chance. Then he went to Stafford, produced Lady Cork’s letter, offered himself as a candidate, and was elected. For Stafford he was member till 1806 — six-and-twenty years.

Lady Cork was a woman of society to the end of her days; she either gave a dinner-party, a rout, or went out every night of her life. Lady Cork would borrow a friend’s carriage without asking her for it, and then innocently suggest that, as the high steps did not suit her short legs, her friend might have them altered for her future use. And not only for short distances or periods would she thus confiscate a carriage, but for the whole day and a long round of visits, leaving the owners to walk home or do the best they could. At home, the old lady, wrote Lady Chatterton, “gave very pleasant parties at her own house, too, and had a peculiar talent for adapting the furniture and everything in the room to promote real sociability and dispel shyness. Many of the chairs were fastened to the floor to prevent people pushing them into formal circles, or congregating in a crowd, or standing about uncomfortably.”

Of this charitable personage, Lady Clementina Davies writes: “Lady Cork was a most remarkable person, very little, and at the time I now mention nearly ninety years old. She used to dress entirely in white, and always wore a white crape cottage bonnet, and a white satin shawl, trimmed with the finest point lace. She was never seen with a cap ; and although so old, her complexion, which was really white and pink, not put on, but her own natural color, was most beautiful. At dinner she never drank anything but barley-water. She had often been at the court of France during the reign of Marie Antoinette, and had frequently met my father there. She said she had never forgotten what the old Princesse de Joinville told her, that la proprele was the beauty of old age, and therefore always wore white. She used to give great routs; and as people met everybody there, her rooms were always well filled. On one occasion, when we went to a large dinner-party at her house, she said to my husband, ‘Don’t be jealous, I have invited a very old friend of your wife; and when I told him I should invite her, he was perfectly delighted at the prospect of meeting her again after so many years. Now,’ she said, turning to me, ‘do you know who it is?’ And to my husband she added, ‘ He was a great admirer of hers when very young.’ I was trying to guess who it could be, when dinner was announced, and Lady Cork seemed very much annoyed and surprised that some person she expected had not come. We all sat down to dinner, and in a short time a note was brought to her. After reading it, she laughed, and sent it round to me. It was as follows : ‘ My dear Lady Cork, — I cannot express my regret that.it is quite out of my power to dine with you. And you will pity me when you hear that I am in bed. A blackguard creditor has had everything I possess taken from me. The only thing he has left me is a cast of one of Vestris’s legs. I must remain in bed till my lawyer comes, as I have not a coat to put on. This is the reason, dear Lady Cork, I cannot dine with you.’ We laughed very much, and as everybody wished to know the joke, Lady Cork told them, and the explanation of the cause of Lord Fife’s failure to keep his appointment made the dinner much more lively than if he had come.”

Lady Cork wrote, or rather had written for her—as she became nearly blind —a charming little note to John Wilson Croker, asking him to dine with her on her ninetieth birthday. His only idea was to convict her of an error as to her age. “I found,” he said, “by the register of St. James’s parish, that she had under-stated her age by one year !”

She lived till May 30, 1840, having finished her ninety-third year. What a wonderful succession of wits, philosophers, beauties, poets, dramatists, novelists, had passed through her salons! In London society she certainly filled up a gap: at that time, stiffness and monotony reigned supreme—Lady Cork broke down the barriers. From her, all who were distinguished in any way found a welcome; she even received the Countess Guiccioli (abovve, Byron’s mistress and friend to Lady Blessington and Count D’Orsay), and made a lioness of her for a season. Even a savage in his war paint would not have been excluded, and by degrees the dull decorum which had marked many of the London drawing-rooms became broken down.

There was always something to see at Lady Cork’s, and her delightful bonhomie and joyousness gave a charm even to her Blue parties. She formed a link between two centuries, and London society owes her a debt of gratitude. Lady Cork was interred in the family vault of the Monckton family, at Brewood, in Staffordshire.

Originally published in 2010