STEP ONE: BODY DISPOSAL – PART TWO

Louisa Cornell

This post is a continuation of the previous post on body disposal in Regency England, For perspective one might want to read through Part One of this series again.

Burial Disposal

Murderers likely buried their victims during the Regency for some of the same reasons murderers bury their victims today. Some did so out of a need to always know where the body was. Some did so out of expediency. It might have been the quickest method to hand at the time. Some did so in order to prevent a body from ever being found. During the Regency there were advantages to burial, especially for those who lived in rural areas. Most people were buried in cemeteries during the Regency. However, it was not uncommon for bodies to be buried on family farms or estates. Poor families buried their dead where they could. A body discovered and dug up in a wooded area, a field or other lonely place might simply be reburied unless the person discovering it thought the body was there as a result of murder.

The degree to which burial destroyed evidence varied. England’s colder weather tended to preserve bodies in the ground save for in the summer months. A laborer, or one who did a great deal of manual labor, was more likely to choose burial as digging was an activity with which they were familiar and at which they were good. Bodies were buried in a variety of spots in the cities. A cemetery that contained open mass graves was the perfect place to dispose of a murder victim so long as those who worked in association with these graves didn’t check too carefully. As horrible as it may sound bodies were found buried beneath the floors of houses and businesses. They were buried in cellars as well. One must remember, especially in cities where people lived in close proximity the smell of a decaying body simply added to the regular stench.

Some things to remember about burying a murder victim during the Regency:

(1) There were no cadaver dogs during the Regency. However, one would be foolish to assume dogs could not find a body. As early as the 16th century dogs were used to track fugitives, enemies, and even runaway wives.

(2) Lime was used in cemeteries in mass graves to speed the decomposition process and to hide the odor. Some murderers in Regency England used lime for pretty much the same reason. However, there were no guarantees and lime took time to get the job done.

(3) Burial did destroy some evidence, but not all. And there were men who could examine the soil from a burial site and match it to the clothes and shoes worn by the murderer.

(4) Burial at a crossroads was less likely to attract attention to the grave. Suicides were not allowed to be buried in cemeteries until the Burial of Suicides Act of 1823.

(5) There were other chemicals available to murderers to aid in the destruction of a body. These were usually used by more educated murderers with the knowledge and the access, although people in trades where lye and other such chemicals were used also had access and understanding. Most of the time these chemicals were used in conjunction with burial as few people had somewhere to store a body long enough for it to be destroyed by chemicals.

A few case studies of burial of a body during the Regency era

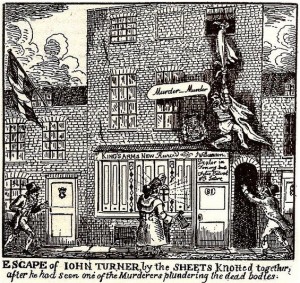

1827 — In 1827 in Polstead, Suffolk Maria Martin was supposed to meet William Corder at a local landmark, the Red Barn, so the two might run off to Ipswich be married. Her family became concerned even after they received letters from her saying all was well. A year later, Maria’s stepmother finally persuaded local authorities that the dreams she’d been having of Maria’s murder had to be true. She’d dreamed off and on all year that Corder had murdered Maria and buried her in the Red Barn. Authorities dug up the floor of the barn and found Maria’s body, identified by some of the clothes she’d last been seen wearing. She’d been shot and buried so deeply no on suspected until her stepmother’s persistence paid off. Corder was tracked down in London, where he had actually married, and returned to Bury St. Edmunds for trial. Unfortunately, he’d kept the red neckerchief Maria was wearing when she went off to meet him. He’d removed it from her dead body before he’d buried her. He was tried and hanged in Bury St. Edmunds in 1828. If one goes to all the trouble of burying a victim one might want to bury all of the victim’s clothing with them.

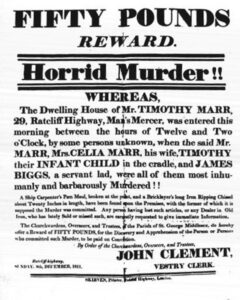

1849 — This particular burial was part of a case sensationalized by the press and the murder ballad writers as The Bermondsey Horror. On 17 August, 1849 two men investigating a missing person, one Patrick O’Connor, went into the home of the missing man’s friends, Frederick and Maria Manning, where O’Connor was supposed to have had dinner on the last night he was seen alive. The couple were not at home, but in inspecting the premises, the investigators noticed a damp spot in the kitchen floor where it appeared flagstones and mortar had recently been replaced. They pulled up the flagstones, dug up the dirt beneath them, and came upon a man’s toe. Once they uncovered the entire body they discovered a middle-aged man, naked, face down, with his legs drawn up behind him and tied with a piece of clothesline. There was also a bloody dress in the grave. Lime had been tossed in over the body, and the face was partially decomposed, but they were able to identify the man by his false teeth. These investigators had learned a bit about investigating a murder as they left the body there and secured the scene. They searched the house and removed items that belonged to the victim. The next day the body was removed from the grave, washed, and the post-mortem was performed on the kitchen table. The victim had been shot and beaten about the head. The Mannings were tracked down, tried, and hanged together. (We will be looking at this case again in other lessons.) Burial of one’s victim in one’s own home can work, but not if one’s home was the last place the victim is rumored to have visited. And leaving one’s own clothing and the victim’s identifiable false teeth in the grave is likely not a good idea either.

Check Back for Part Three of this series soon !