Victoria here, inviting you to come with me to Regency London! Do not forget to don your special eyeglasses, the ones that will eliminate all evidence of city development after 1820 or so, including Victorian remodeling, post-Blitz reconstruction, contemporary skyscrapers, autos and buses, and modern clothing.

Substitute for horns, diesel engines and ever-present sirens the clip clop of hooves, the squeaking of cart-wheels and the cries of peddlers and hawkers of milk, eel pies, fresh buns: “Who will buy my ….”

We shall start at the old address, No. 1 London (above), the site of Apsley House, home of the Duke of Wellington. The original Adam house was re-faced in Bath stone; the Duke entertained here, particularly at the Battle of Waterloo annual anniversary banquet, beginning in the appropriately named Waterloo Gallery.

I will not go into raptures over Apsley and its treasures — we have done that before on this blog. In fact, several times, and you’ll find the website here. But keep in mind that neither the exterior nor the interior are original. While the exterior was remodeled before 1820, the interiors reflect more of the tastes from the Victorian era.

Here is the entrance, as it was refaced in Bath Stone after the Duke purchased Apsley House from his brother Richard, Marquess of Wellesley, in 1817. Originally the house was smaller and finished in red brick.

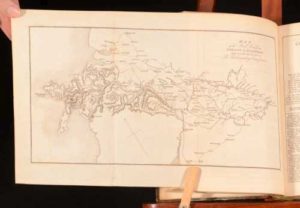

The map below shows the route we will take on this visit to Regency London. We start at Apsley House, approximately at A on the map, which is the tube stop just outside of Apsley House. The layout of the streets in 2011 is quite different from 1811. Today the broad boulevard of Park Lane (in green) connects with Piccadilly and other streets in a dizzying traffic circle. Apsley House is entirely cut off from the other streets, and the buildings that stood beside it were long ago demolished. The rather dark picture above shows how Apsley House stands isolated behind all the traffic.

Today it sits in the eastern most part of Hyde Park. From Apsley, we will walk in a generally easterly direction toward B on the map, which is Piccadilly Circus, also non-existent in 1811. Along Piccadilly, we will see a few remnants of the Regency Era and just before we get lost in Piccadilly Circus, we will retrace our steps to the top of St. James Street (on the map a tiny bit to the right of the Green Park tube sign) and walk down (southerly) St. James Street until it ends at — what else? — St. James Palace, beyond Pall Mall.

Above is a building variously known as Cambridge House and the former In and Out Club. This imposing house was built in the mid 18th c. for the 2nd Earl of Egremont. It was later owned by the 1st Marquess of Cholmondeley and then by Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge. From 1855 to 1865, it was known as Palmerston House, where Lord Palmerston, Prime Minister, and his wife, Emily, Lady Palmerston (nee Lamb, formerly Countess Cowper) entertained and conducted much of the business of the government. In the 20th century, it became the Naval and Military Club, often called the In and Out Club, after the large signs on the pillars in front of the courtyard. In 1996, the Naval and Military Club moved to different premises in St. James Square. The building then stood empty and sadly neglected until last year, when construction began on what will be yet another hotel. In fact, the whole of the area around Apsley House will soon be comprised of hotels before too much longer.

Moving eastward, and also on the north side of the street, we arrive at Burlington House, now the home of the Royal Academy of Art. There are remnants of the Regency era building here, but the exterior and much of the interior are greatly altered, not to mention the artwork in the courtyard.

The house and its grounds were remodeled by the same Lord Burlington that designed and built Chiswick House in grand Palladian Style. Like many of the mansions on Piccadilly and in Mayfair, it used to have gardens, extensive courtyards, stable blocks, all the accouterments of country mansions — which they once were. As the West End became more and more desirable, these gardens and most of the courtyards were built over.

Above are the John Madejski Fine Rooms in the Royal Academy, which have been restored close to their appearance in the 18th century. These rooms are often open without charge to visitors and display portraits of RA members such as Reynolds and Gainsborough. The other galleries have been greatly altered from the original and house changing exhibitions.

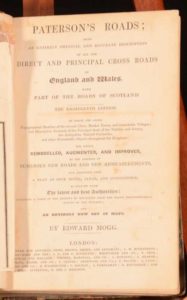

Next door, we find Albany where so many famous Regency gentlemen (not to mention numerous fictional heroes) lived. The house was once the home of Lord and Lady Melbourne, then the Duke of York, before it was converted to apartments. Byron had rooms here, as did (much later) Georgette Heyer. Below, two views of Albany, from the front and the side. Across Piccadilly is Hatchard’s Book Shop.

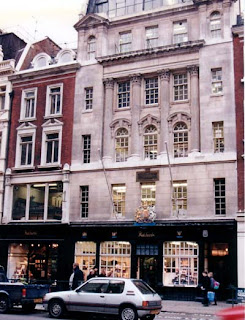

|

| Hatchards Book Store, 187 Piccadilly, Est. 1797 |

A bit farther east on Piccadilly (assuming you can tear yourself away from all the tempting titles at Hatchards) is St. James Church, 197 Piccadilly, built in 1684 and designed by Sir Christopher Wren. Its interior has many carvings by Grinling Gibbons, and despite some renovations in the 19th and 20th centuries, it is much as it appeared during the Regency.

Now retrace your steps past Hatchards and walk to Fortnum and Mason, on the corner of Piccadilly and Duke Street. Although it began in 1707 in St. James Market, the large building is modern. Nevertheless, you may want to sample one of the restaurants or at least take home a catalogue of their mail-order wares. Visit the website here.

|

| Fortnum and Mason, 181 Piccadilly, est. 1707 |

Proceed westerly to the corner of St. James Street and turn left, or south. At the bottom, you will see St. James Palace, as I photographed it from a distance.

|

| Today’s view of St. James |

From Ackermann’s Microcosm of London, the scene at a drawing room in St. James Palace in 1808. St. James Palace was the official residence of the King. Even today, foreign ambassadors serve at the Court of St. James, though they are received by the Queen at Buckingham Palace.

On your walk from Piccadilly to St. James Palace, most of the buildings you pass were constructed later than the Regency, but not all, for here are several of the famous men’s clubs of St. James and several shops with roots in the era.

|

| Whites Club |

|

| Brooks Club |

|

| Boodles Club |

|

| Berry Bros. and Rudd, Wine Merchants, est. 1698 |

|

| Lock and Co. Hatters, est.1676

|

A walk around Regency London with tour guide Kristine Hughes is included on the itinerary for Number One London’s Town & Country House tour in May 2024. Complete itinerary and details can be found here.