So, the Rye Esplanade is also home to the local bus service, as well as to the trains. Victoria had suggested that we visit Appuldurcombe House, and as that was the only thing on our agenda this day, we decided to take the local bus there, which would allow us to see more of the Isle of Wight along the way. Sitting on the top of the bus, we had great views.

We let the driver know that our destination was Appuldurcombe and he agreed to let us know when our stop was approaching.

“So, what’s at Appuldurcombe, then? Capability Brown, Chippendale and knife boxes?” I asked Vicky.

“You don’t know Appledurcombe?” she asked.

“Never heard of it,” I replied.

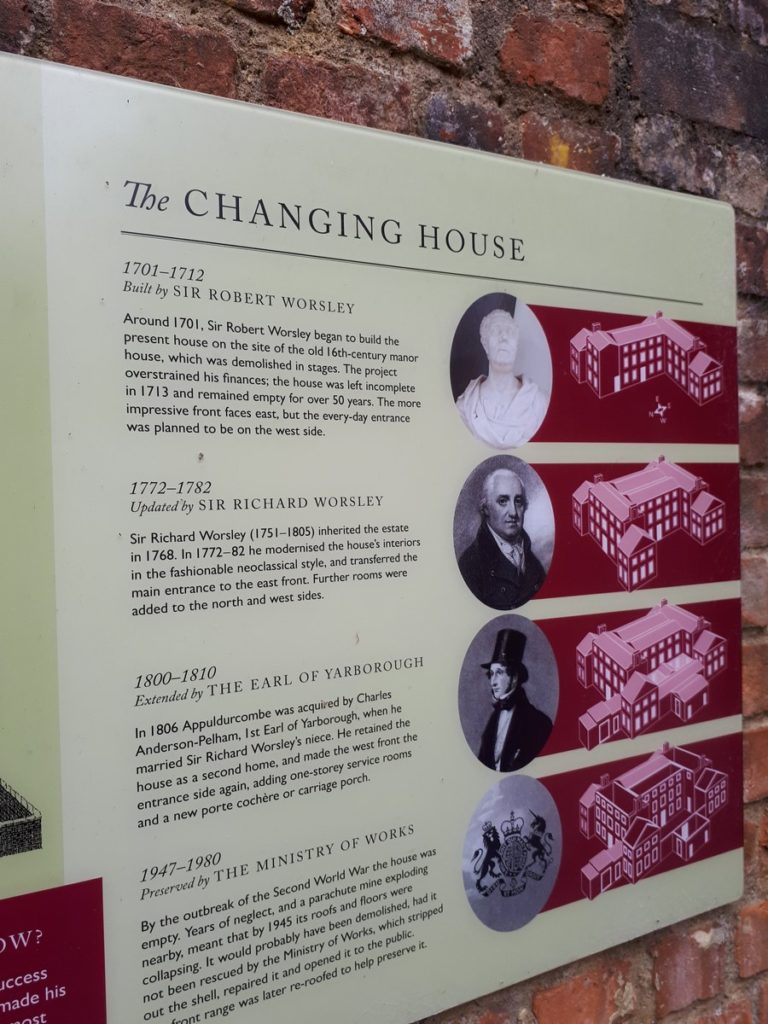

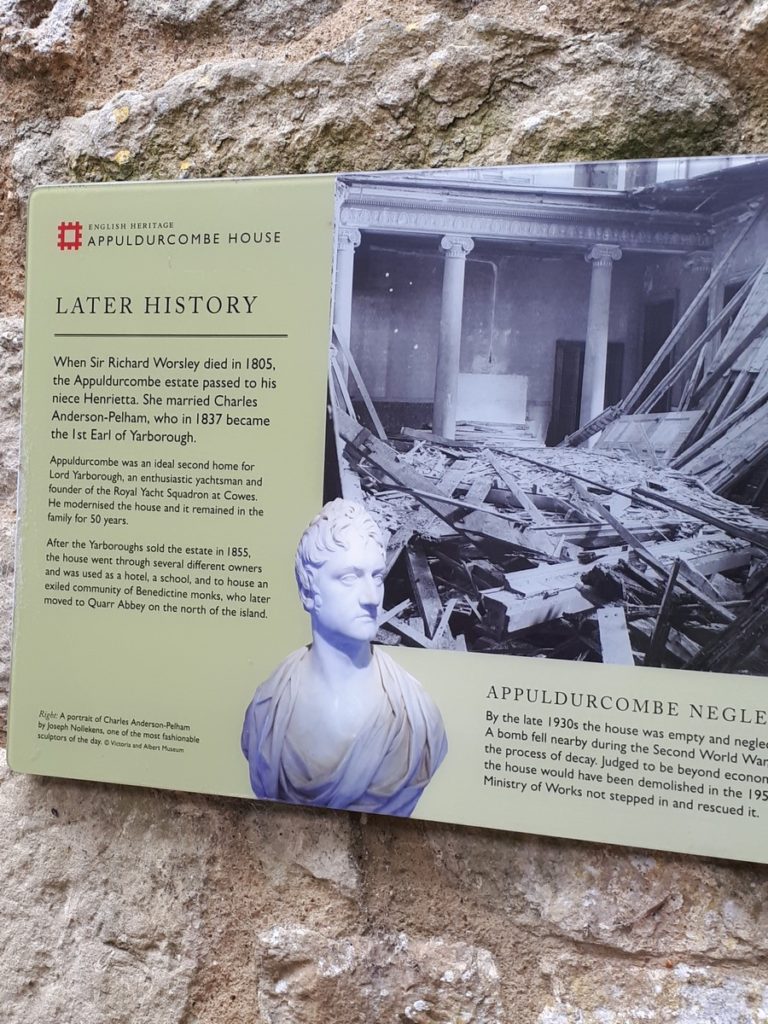

“It’s been abandoned. It’s a ruin. A shell of its former self,” Vicky informed me.

“Like Sutton Scarsdale?” We’d visited Sutton Scarsdale the previous year, on Number One London’s Country House Tour.

“Yes, except that there aren’t any plans to restore Appledurcombe. They’ve just shored up the shell and you’re actually allowed to walk around the ruins.”

Now this was a new take on the stately home. I sat back and watched the scenery go by – views from the sea cliffs, a handful of towns and villages and a wide variety of architectural styles of houses and shopfronts.

About an hour later, our bus driver let us know that the next stop would be ours. “See there, that’s your street,” he said, as we passed it. “Bus stop is just here. Walk back and down that lane and you’ll find Appuldurcombe House.”

And so Vicky and I set off, eyes wide at the Midsomer Murders look of the lane and its charming houses. So typically English. So quaint.

After a while, the lane began to go uphill. Still, we trudged.

After a while, the lane began to go uphill. Still, we trudged.

“I haven’t seen a single sign for Appuldurcombe House,” said Vicky. “Have you?”

“No,” I replied. “But the bus driver said it was just down this lane and walkable.”

“Ha! You know what the English are like. If we’d asked if we could walk from here to Edinburgh, they’d have said yes. Never mind that it would take us a week to get there.”

I knew from experience that she was right. But I didn’t think the nice bus driver would have led us down the garden path, so to speak. The hill grew steeper, though you can’t tell by these photos.

“Can you see anything that looks like a ruined house?” Vicky asked.

“Can you see anything that looks like a ruined house?” Vicky asked.

“Nope. You sit here on this wall and I’ll go ahead and see if I can spot the house,” I told her.

And so I walked up hill, up the lane and around the turn and this is what I found.

A field full of cows. Friendly cows. As soon as they saw me, they began to make their way over to the fence. A litter of Labrador puppies could not have been more eager to see me.

“Vicky! Come here!”

“What do you see? Is it the house?”

“No. Better. Cows!”

Caution: Many Cow Photos Ahead

Bonus – sheep!

Cows and sheep!

As evidenced by the plethora of photos we took, we spent quite a bit of time with the cows – petting the cows, photographing the cows, talking to the cows, communing with the cows, but at last Vicky said, “Well, should we head back?”

“No! Our aim was to see Appuldurcombe House. We can’t give up now. Stay here and I’ll go ahead and see what I can see.”

I walked ahead about fifteen steps and this is what I saw.

I walked the fifteen steps back, “The house is just there, around the bend.”

Off we set down the path, through the wood and a field of bluebells.

It was all a bit Hansel and Gretel-ish.

Finally, we had our first, up close glimpse of Appuldurcombe.

Finally, we had our first, up close glimpse of Appuldurcombe.

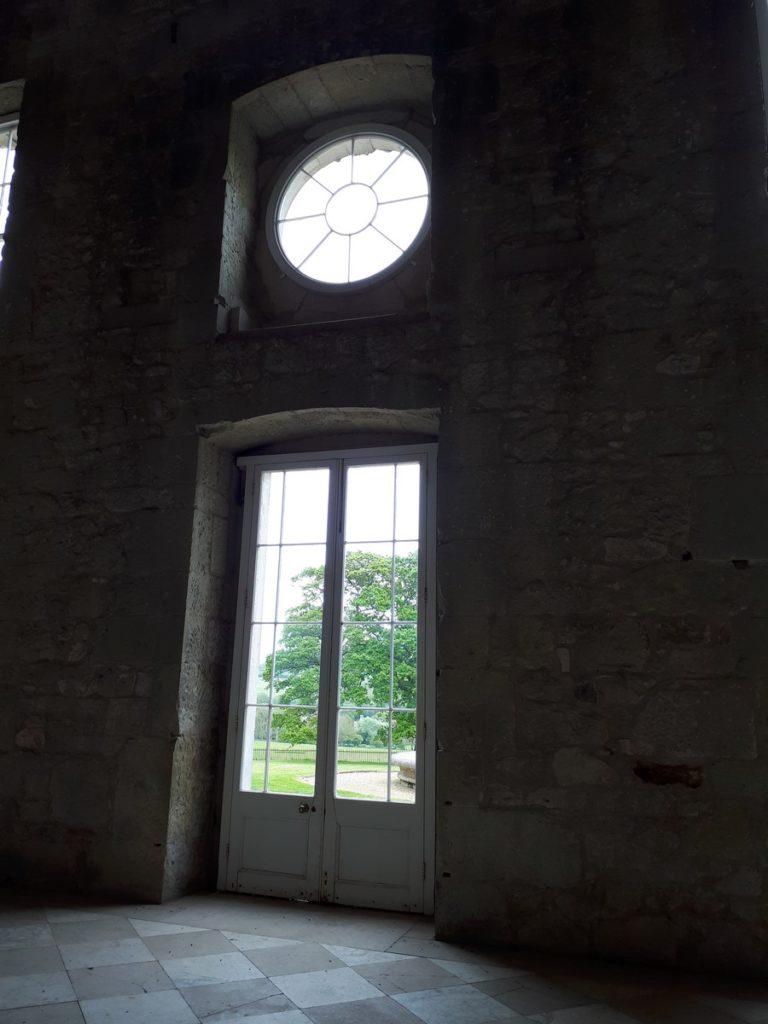

And then, there it was before us. In all its ruined glory. We were both gobsmacked.

An honest to goodness ruin. And not another soul about. Not another tourist, not a caretaker, not Vincent Price, not even a wicked witch. We had the place well and truly to ourselves.

“Are you sure we’re allowed to wander around?” I asked.

“That’s what the website said,” replied Vicky. “I don’t see that anything is roped off, do you?”

I did not. And so we wandered.

I don’t know how long we were there, but we investigated every bit of Appuldurcombe, for the most part in silence. It’s very eerie being alone there, among the ruins. It’s a far cry from my usual stately home visits. You do feel as though the house is waiting. For what, I don’t know, but Appuldurcombe still stands proudly, refusing to completely give way to ruin; recalling grander times, listening to the echoes of long silenced family voices, keeping watch over the nearby Wroxall village.

We never did see another living soul.

By this time, Peter Mark Roget, almost 40 years of age and unmarried, had a thriving medical practice and had become a member of the Royal Society; he was the one called to his uncle’s bedside. Sir Samuel had slashed his throat with a razor, inconsolable after the death of his wife, whom Roget had attended in her last, fatal, illness. (This incident is described in tragic detail in the opening pages of the Kendall biography.Sir Samuel’s demise was a great loss to his family and to the nation. A good part of the blame for his suicide, alas, was attributed later to the insensitivity of the medical treatment of his nephew, Peter Mark Roget. This blame, unfortunately, may well have been warranted.Kendall states “no one questioned Roget’s concern for his uncle” but “a consensus emerged that he had failed to grasp the full extent of Romilly’s emotional agony” upon the loss of his wife. But, again, severe depression ran in the Romilly family, and perhaps no physician could – at that time – have done anything to alleviate Roget’s uncle’s grief and deterred him from suicide.

By this time, Peter Mark Roget, almost 40 years of age and unmarried, had a thriving medical practice and had become a member of the Royal Society; he was the one called to his uncle’s bedside. Sir Samuel had slashed his throat with a razor, inconsolable after the death of his wife, whom Roget had attended in her last, fatal, illness. (This incident is described in tragic detail in the opening pages of the Kendall biography.Sir Samuel’s demise was a great loss to his family and to the nation. A good part of the blame for his suicide, alas, was attributed later to the insensitivity of the medical treatment of his nephew, Peter Mark Roget. This blame, unfortunately, may well have been warranted.Kendall states “no one questioned Roget’s concern for his uncle” but “a consensus emerged that he had failed to grasp the full extent of Romilly’s emotional agony” upon the loss of his wife. But, again, severe depression ran in the Romilly family, and perhaps no physician could – at that time – have done anything to alleviate Roget’s uncle’s grief and deterred him from suicide.