Guest Post

ANDREA K. STEIN

Imagine a small crew of men rowing up a mosquito-infested jungle estuary in the darkness of night, silently gliding through lands dominated by warring tribal chiefs. Their mission? Stop trafficking in human slavery. Does this sound like the plot for a movie based on a special forces or Navy SEALS op?

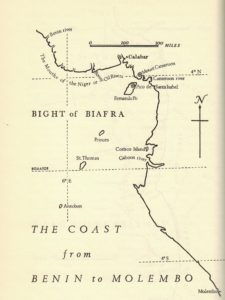

Actually, the year is 1820, and the men are ordinary Royal Navy sailors and marines. They don’t have the luxury of night-vision goggles, high-tech weaponry, or medical access to a cure for the dreaded jungle fevers. They’re the men of the African, or Preventative, Squadron, as they were more commonly known in the 19th century. The place is the Rio Pongas estuary on West Africa.

Between 1807 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 ships involved in the slave trade and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard those vessels.

Those numbers are staggering, considering what the squadron had to work with, but perhaps it makes more sense to look at this accomplishment in the context of the life of one of those slaves.

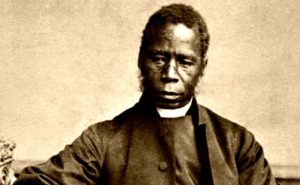

Samuel Ajayi Crowther was kidnapped at 12 or 13 into slavery in 1821 by a neighboring tribe and sold to Portuguese slavers who placed him on a slave vessel for transport. The African Squadron’s “HMS Myrmidon,” under the command of Sir Henry Leeke, detained Adjai’s ship before it could leave port.

Ajayi and the others were rescued and taken to Freetown, a settlement for liberated Africans in Sierra Leone. Educated in a missionary school in Freetown for the next few years, he was baptized on December 11, 1825, and took the name Samuel Crowther.

Crowther excelled in languages, including English, Greek, Latin, and Temne. In 1826 he attended Islington Parish School in England, returning a year later to study as a teacher at Fourah Bay. In time, he became a teacher there himself. In 1841 he became a missionary on the Niger. After this, he was recalled to England where he trained as a minister and was ordained by the Bishop of London in 1843.

In the same year, he returned to Africa and opened a mission of his own in Abeokuta, Nigeria. He translated the Bible into Yoruba, wrote a Yoruba dictionary and published several books of his own on African languages. In 1864, he became the first African Bishop ordained in the Anglican Church.

When I began thinking about a group of heroes for my latest series of historical romances, my research and the workings of my quirky mind led me to the men of the African Squadron. Some historians believe these men took on this work only for the prize money. Depending on the mood of the prize court in Freetown, and the politics back in London, the crew could benefit from the seizure of each ship and each slave freed. However, on the slaver side of the ledger, some very powerful forces were still at work, both inside and outside of England, and often, the captains and crews were denied any payment by the courts.

The mortality rate among the men of the squadron was staggering. On some expeditions, an estimated one-third to one-half of all sailors died aboard individual ships. The marine surgeons who sailed with the West African Squadron are credited with finally linking the mosquito to the spread of fever and finding treatments. It’s difficult to imagine men would work under these conditions only for the money. They had to be courageous, fearless, and believers in the cause.

Although Parliament had passed a law outlawing slavery in 1807, the act was not fully operational until January 1808. However, at that time, England was fighting France in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean. There were approximately 795 Royal Navy ships in commission and they were very thinly spread.

By November 19, 1819, the war with France had been over for four years, and the Royal Navy at last had ships to spare. By this time the squadron was led by Cmdr. Sir George Collier who fought under Nelson at the Battle of the Nile. He was given six ships to cover a coast of about 2,500 miles, an area equivalent to the U.S. East Coast, from Maine all the way around Florida to New Orleans.

The Squadron’s lives in letters, portraits, diaries, and ships’ logs are part of a wonderful exhibit at the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth, England. Fortunately, most of the items have been digitized and are available online.

Sources:

National Museum of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy and the Slavers by W.E.F. Ward

Enforcing Abolition at Sea 1808-1898 by Bernard Edwards

Sweet Water and Bitter by Sian Rees

The first in the Men of the Squadron series, “Pride of Honor,” is up for pre-order on Amazon.

What if two people determined to marry anyone

but each other end up falling in love?

A hatpin-wielding, parasol-armed poet with a maddening Royal Navy officer in tow races against time to attract the marital attentions of the perfect “gentleman of the ton.”

Sophia Brancellli, the orphaned, illegitimate child of a duke’s daughter and an Italian poet, is on a mission. She must ensure her marriage to a “suitable gentleman of the ton” before her twenty-first birthday or she’ll be destitute, per the terms of her ducal grandmother’s will. Close to having her own poems published, Sophia has her hopes dashed each time by someone revealing her secrets. That same someone so desperately wants her to fail the terms of the will, they’re willing to commit violent acts to ruin her reputation.

Captain Arnaud Bellingham has ascended the ranks of the Royal Navy in spite of his half-French heritage by proving himself at the Battle of Algiers and with the West African Squadron. He seeks a simple marriage of convenience to a mature woman, a widow who has been his sometime mistress the last several years. The very thing he does not want, an exotic Italian innocent, literally falls into his life when he rescues her from kidnappers, although she disputes she needed saving. And now, honor and duty dictate he has to waste the rest of his leave guarding her through the mad whirl of the Season.

Excerpt:

Sophie lost her balance and sat down with a thump at the edge of the street. Shaking, she sank her elbows to her knees and rested her head in her hands. Her parasol had rolled to the edge of the walkway. At a sharp cramp in her hand, she realized she still clutched her trusty hatpin. After a restorative breath, she looked up into the deeply tanned face of a Royal Navy officer in full uniform.

He knelt in front of her, asking question after question. “Are you hurt? Who did this to you? Are you with a chaperone?”

Blood dribbled from his wrist, staining his white glove. Zeus! The hatpin. She knew she should provide him with some answers, but couldn’t. She could barely breathe properly, so shaken was she by the encounter with the unknown men who’d tried to drag her toward a waiting hack carriage.

He grasped her by the shoulders. The warmth of his touch seeped through the thin muslin of her dress, and his solid competence fortified her courage. The runaway terrors slowed, allowing her to breathe normally again.

The first thought to pop into her head once she’d settled a bit was: Respectable women of the ton did not find themselves in situations like this. This was the sort of turmoil that might befall the actresses who had kept company with her late father.

“Are you hurt?” The naval officer shed his gloves and ran his hands down her arms as if seeking injuries. “By Jupiter! Is this your weapon?” The hatpin rolled into his hand from her slackened grasp, and he tucked it safely within a pocket. His frown softened a bit, he shook his head, and gave a low chuckle.

He clasped her hands as if he feared she might break and smoothed his thumbs over the soft pads beneath her thumbs. If the stranger continued his exploration for injuries, Sophie feared she might expire from pleasure. If only he knew the ink-stained fingers her white gloves hid.

More about Andrea

Andrea K. Stein is the daughter of a trucker and an artist. She grew up a scribbler. The stories just spilled out.

After writing and editing at newspapers for twenty-five years and then a short, boring stint as a consultant to commercial printers, she ran away to sea for three years to deliver yachts up and down the Caribbean.

She earned her USCG offshore captain’s license, but perversely, now writes romance set at sea while wrapped in sweaters and PJs in her writing room in Canon City, CO.

She has eight published romance novels available on Amazon. Three of those titles have been honored with awards. “Secret Harbor” earned a first place in the Pikes Peak Writers Fiction Contest in the romance category; “Fortune’s Horizon” finaled in the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers Romance category; and the latest novel, “Pride of Honor,” finaled in the national 2018 Beau Monde Royal Ascot Contest.

Join Andrea on Facebook and come find Andrea along with the Squadron officers and get advance, exclusive news of the adventures to come on Facebook in her private group, Men of the Squadron.

For more high seas excitement, content available nowhere else, and occasional fun rewards, sign up for Andrea’s newsletter. Don’t forget to visit Andrea’s website or her Pinterest page!

Coming Soon – Other Titles in the Men of the Squadron Series

Pride of Honor – February 2020

Pride of Duty – May 2020

Pride of Country – August 2020

Pride of Service – November 2020

.jpg)