THE LAMB AND FLAG

COVENT GARDEN

33 Rose Street, London

LOUISA CORNELL

The name of this pub is derived from the Bible verse John 1:29, where John the Baptist sees Jesus and exclaims, “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.” The flag is the flag of St. George. The symbolism was long associated with the Knights Templar and the Fleet Street entrance to the Middle Temple of the Bar has a sculpture of the Lamb and Flag on its keystone with the date 1684.

Known as the oldest tavern in Covent Garden, the basic building for this establishment was built in 1623 during the reign of James I, although the specific association of the site with an inn or tavern is less certain. The structure has undergone a great many renovations and rebuilds, but the original timber frame remains. Over the years the rebuilds and alterations have sought to keep the original details of the building. This includes a parapet that runs the width of the top of the building. There is even a carving of the Lamb and Flag at the center or the parapet.

The spot has a connection to a number of poets and writers, even before any recorded history of its use as a tavern. Poet and satirist, Samuel Butler (1613-1680) did live on Rose Street (formerly known as Red Rose Street) in the area of the narrow alley where the Lamb and Flag is now located. If there was a tavern there he is said to have been a patron. Dickens was a customer there in his youth as he worked at a boot blacking establishment nearby when he was in his teens. The playwright, Richard Sheridan frequented the tavern at this location and even fought a duel on the corner of nearby Bedford Street in 1772 over an insult printed in the Bath Chronicle.

A more documented link to the poet John Dryden (1631-1700) is associated with what was called Rose Alley where the present day entrance to the saloon bar of the Lamb and Flag is located.

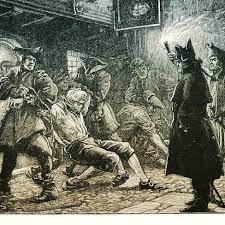

Today from Rose Street to Floral Street down the side of the Lamb and Flag is a very narrow alley, Lazenby Court, so narrow that in order to pass people must turn slightly sideways. The event that took place on December 18/19, 1679 was called the Rose Alley Ambuscade. John Dryden was attacked and nearly killed by a group of masked ruffians. He was supposedly on his way home from Will’s Coffee House on the corner of Russell Street and Bow Street. Dryden wrote a great many poems and essays vilifying the elite of London and the royal court. Rumor has it the thugs were hired by John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester (author of some very naughty poetry himself) and / or the Duchess of Portsmouth, mistress of King Charles II at the time – two of Dryden’s targets. The culprits, however, were never made known, in spite of a handsome reward offered for their names.

“Whereas John Dreyden, Esq. was on Thursday the 18th instant, at night, barbarously assaulted and wounded in Rose-street, in Covent-Garden, by diverse men unknown: if any person shall make discovery of the said offenders to the said Mr. Dreyden, or to any Justice of the Peace, he shall not only receive fifty pounds, which is deposited in the hands of Mr. Blanchard, goldsmith, next door to Temple-Bar, for the said purpose, but if he be a principal or an accessory in the said fact, his Majesty is graciously pleased to promise him his pardon for the same.”

London Gazette, No. 1472, 29 December 1679

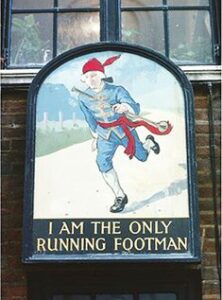

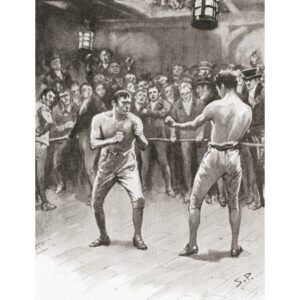

It was first recorded as a tavern in 1772 when it was known as the Cooper’s Arms. During this era the establishment gained its second name – The Bucket of Blood – due to the bare knuckle fights that took place in the room upstairs or in the courtyard outside the tavern on a weekly basis. This nickname continued to hold true even after it finally became the Lamb and Flag in 1833.

These activities made the Lamb and Flag a popular spot for the bruisers, bucks, and gentlemen of the Georgian Era. It also provided the pub with its current ghostly resident, George. But, I’ll let someone who works there tell you about George.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8V52ynVYdM

The bouts of bare knuckle fighting are over at the Lamb and Flag these days. Although rumor has it one might have to put up one’s “fives” to access Sunday roast in the Dryden Room upstairs as it is a very popular spot for Sunday dinner with the locals. Just don’t take any bets with a French sailor named George. Nobody likes a gentleman who doesn’t pay his bets. And if you write poetry poking fun at the nobility it is best to stay clear of the alley next to the pub.

_by_Thomas_Lawrence.jpg)