So, then, after all this, how did he come to compile that outstanding reference work, Roget’s Thesaurus? It seems like such a departure from what his life was.It seemed, though, that ever since his childhood, Roget was fond of making lists. Kendall opines that this gave order to an otherwise confused, if not chaotic life, with its moves across continents, the death of one parent and the mental instability, in a family prone to severe depression, of another. Making lists, sorting things into categories, making sense of a world that was puzzling and no doubt upsetting to him, was a source of satisfaction and provided a modicum – or more than a mere modicum — of stability.

I believe that Kendall rightly describes Roget as an obsessional personality, but I would venture even further. It’s interesting, this making of lists, when taken into consideration with Roget’s intelligence, his genius with science and mathematics, plus the strains of mental illness in his family, and his inability to communicate well with other human beings. Perhaps something else was going on. It was said of Peter Mark Roget that he got along with words much better than he ever got along with people, and there is probably a great deal of truth in that surmise. Imposing order on words, categorizing things –whether space, matter, affections, et al. – seemed to settle his perhaps too-active mind. And this made me wonder if he might have had a form of high-functioning autism now called Asperger’s Syndrome. (This condition was not described until the mid-20th century, too late for Roget to have been diagnosed.)

The symptoms of autism are many, but consider as one example, the problem of not being able to recognize how severely depressed his uncle was in his last days. Was Roget unable to relate to him – a prime “tell” for autism sufferers – and did that lack of empathy play a large role in his uncle’s doing away with himself? Was he constitutionally unable to read the signs of a soul in distress, even one who had been so very close to him? This constant list-making, this never-ending attempt to impose order on a world that confused him, this outward manifestation of his restless intellect, was this perhaps another “tell”? Impossible to diagnose from so far way in time from Roget’s world, but other incidents in his life confirm his continual problems with social interaction.

Kendall does not deal with the possibility of autism; it is my own notion, for whatever it is worth, but he does make a forceful case for OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder. He discusses Freud’s 1913 paper on the condition, noting the psychiatrist’s finding that “obsessions, which tend to first appear between the ages of six and eight, serve the function of helping people ward off intense and painful emotions such as anxiety and hate… [and that] obsessionality…is remarkably consistent over the life span.”

The author goes on to state: “That was certainly the case for Roget; some eighty years after he started his notebook, he was harnessing the same obsessive energy to churn out new editions of his Thesaurus.” Whatever psychological condition(s) Peter Mark Roget might have had, his genius was in his ability to compile words brilliantly into his many lists, in notebook after notebook, starting at the tender age of eight. Roget was in a long tradition of word-compilers, but he was the very best. His contribution to anyone who struggles to find the right word is unparalleled.

As Kendall notes: “For Roget, the careful use of language depended on understanding not only the meanings of individual words but also the relations between them.” Further, “These neighboring lists of opposing ideas, he believed, opened up all kinds of new vistas for readers.” One of the intriguing aspects of Kendall’s book is his clever use of these lists throughout the text, and also in chapter headings.

For instance, Chapter 7, Mary, which introduces Roget’s wife, lists synonyms for Marriage:

…MARRIAGE, matrimony, wedlock, union, match, intermarriage, coverture, vinculum matrimonii.

A married man, a husband, spouse, bridegroom, benedict, neogamist, consort.

A married woman, a wife, bride, mate, helpmate, rib, better half, feme covert.

(Bet there are a few words here you haven’t come across!)

And in what was apparently a time-honored tradition in the Roget-Romilly clan, Mary Hobson was rich, the daughter of a wealthy Liverpool merchant, and considered beautiful. Kendall notes that she was also, “Roget’s opposite…with a lively sense of humor… [and she] exuded warmth.” He married her in 1824, when she was 29 and he was 45; he was sixteen years older. She seems to have been the ideal wife for someone like this obsessive polymath. She even attended all his lectures and took notes! Her diaries show her pride in the success of these public events featuring her husband. As Kendall comments: “Though Roget couldn’t always connect with others one on one, he never failed to dazzle his audience.”

Alas, the bad luck of the Rogets when it came to their physical and mental health was to run its appointed course. In 1833, his 38-year-old wife died of cancer. They’d been married just under ten years. Kendall notes: “Roget’s immediate reaction was the same as the one that followed his uncle’s suicide: emotional paralysis.” Although his in-laws were kind to him in his loss, they immediately stopped the monies they’d been regularly sending to Roget since his marriage to their daughter. (I found this startling and have to wonder what sort of dowry arrangement Roget had made with the wealthy Hobson family, but there is no further explanation.)

A few years after his wife’s death, Roget hired a new governess for his two children, a Margaret Spowers, the daughter of a wealthy Hampstead businessman. (Always these wealthy women! Is a pattern emerging here?) During the summer of 1840, Roget and the governess were to begin to live together as man and wife, but never to marry. The nature of their relationship apparently so embarrassed Roget’s family that they “would do everything they could to cover [it] up,” according to Kendall.

The relationship no doubt contributed to the emotional breakdown of Roget’s fragile daughter Kate, who was made to leave their home, eventually residing for some years with her former governess, the botanist Agnes Catlow. (When Margaret Spowers died – leaving nothing of her considerable wealth to Roget – oddly harkening back to being cut off financially by his wife’s relatives– Kate returned to her father and was his companion until his death.More drama was to come. In the mid- to late-1840s, Roget was involved in a series of “alleged missteps” at the Royal Society and perhaps forced to resign his prestigious post as Secretary, though he “refused to take responsibility for any of his questionable behavior.” Were these “missteps” and “questionable behavior” further manifestations of his problems in dealing with others? It was 1847, he was now 70 years old, and his life-long issues with insensitivity, coupled now with challenges to his scientific credibility, were coming under close scrutiny. He did resign.

Like the crisis with his uncle’s death, this was not a good time for Roget. But, as Kendall writes: “As the curtain fell on his academic career at the end of 1848, Roget wasn’t quite ready to pack it in. His mind was sharp as ever, and he was still teeming with ambition.” Taking a look at other works then available that dealt with English synonyms, Roget decided at long last to publish his lists, which he felt were superior to anything in print. The first edition of Roget’s Thesaurus, 1,000 copies published in the spring of 1852 by Longman, quickly sold out. Reviews, Kendall notes, were “glowing.” It has remained solidly in print for over one hundred and fifty years. After Roget’s death in 1869, future editions were edited by his son John Lewis Roget and his grandson Samuel Romilly Roget.

His contract for the first edition was ½ of the profits from all sales; with later editions it was to be 2/3 of the profits. He did very well financially from his lists of words! And what about Roget and Dr Johnson, the maker of that formidable dictionary of the English language? What further parallels and similarities might lie between these two geniuses of the written word? Dr Samuel Johnson’s genius lay in defining words, and his Dictionary – the first real dictionary of the English language — broke new ground; his was an altogether different category of genius. But it is tantalizing to note that Johnson also had an obsessive personality and was prone to tics and strange behavior. (At one point there was a theory bruited about that he exhibited the symptoms of Tourette’s Syndrome.)

Johnson did have a strange routine of counting his steps when he came to a door so to enter by the correct foot, and, like the fictional detective obsessive character Monk in the American television series, with his need to touch light poles and mailboxes, Dr Johnson apparently needed to touch all the lampposts on the street as he walked to and from his house on Gough Square. Word nerds are interesting and amusing folk, to be sure.

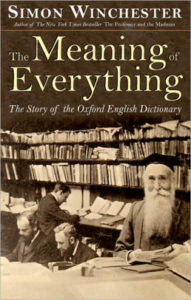

Postscript: Simon Winchester, who was at the time writing a book on the OED (Oxford English Dictionary)* launched a scathing attack on Roget’s work a few years ago, declaring that it was “a serious force for bad” as “uncritically offering up lists of alternative words” leads to poor writing habits, to “our current state of linguistic and intellectual mediocrity” and to a language that is “decayed, disarranged, and unlovely.” He continued on this track for 15,000 furious words – none of which, he said proudly, had been assisted by the use of any thesaurus. He also went on to disparage folks who dare to use the book to solve crossword puzzles, insisting that using a reference book of any kind to complete a puzzle is “simply not done”.

Oh, dear, I do admire Winchester’s writing – I think I own most of his very well-written books – but I do not think it’s possible to disagree more with him on all these points. Speaking as a reference librarian and as a wordsmith, I do not – and will not, ever – hesitate to say that reference books are a great help in finding answers to all kinds of questions and clarifying one’s thoughts, and that using a thesaurus to find the right word(s) teaches us a great deal.

Reference books are not crutches, but sturdy ladders to higher learning and understanding. Rather than being – as Winchester says – a kind of vulgar substitute for thinking – they are stimuli to thinking. We owe Roget, and Webster, Johnson, James Murray, and other lexicographers/word nerds a great deal; I, for one, am willing to acknowledge that, and to express my eternal gratitude to these giants who loved words as much as I have loved them every day of my life.

By this time, Peter Mark Roget, almost 40 years of age and unmarried, had a thriving medical practice and had become a member of the Royal Society; he was the one called to his uncle’s bedside. Sir Samuel had slashed his throat with a razor, inconsolable after the death of his wife, whom Roget had attended in her last, fatal, illness. (This incident is described in tragic detail in the opening pages of the Kendall biography.Sir Samuel’s demise was a great loss to his family and to the nation. A good part of the blame for his suicide, alas, was attributed later to the insensitivity of the medical treatment of his nephew, Peter Mark Roget. This blame, unfortunately, may well have been warranted.Kendall states “no one questioned Roget’s concern for his uncle” but “a consensus emerged that he had failed to grasp the full extent of Romilly’s emotional agony” upon the loss of his wife. But, again, severe depression ran in the Romilly family, and perhaps no physician could – at that time – have done anything to alleviate Roget’s uncle’s grief and deterred him from suicide.

By this time, Peter Mark Roget, almost 40 years of age and unmarried, had a thriving medical practice and had become a member of the Royal Society; he was the one called to his uncle’s bedside. Sir Samuel had slashed his throat with a razor, inconsolable after the death of his wife, whom Roget had attended in her last, fatal, illness. (This incident is described in tragic detail in the opening pages of the Kendall biography.Sir Samuel’s demise was a great loss to his family and to the nation. A good part of the blame for his suicide, alas, was attributed later to the insensitivity of the medical treatment of his nephew, Peter Mark Roget. This blame, unfortunately, may well have been warranted.Kendall states “no one questioned Roget’s concern for his uncle” but “a consensus emerged that he had failed to grasp the full extent of Romilly’s emotional agony” upon the loss of his wife. But, again, severe depression ran in the Romilly family, and perhaps no physician could – at that time – have done anything to alleviate Roget’s uncle’s grief and deterred him from suicide.