One of the best and most concise Waterloo videos we’ve come across –

One of the best and most concise Waterloo videos we’ve come across –

By Guest Blogger Regina Scott

Once more we return to the boxing square! If you missed part one of this series, you can find it here. And part two is here.

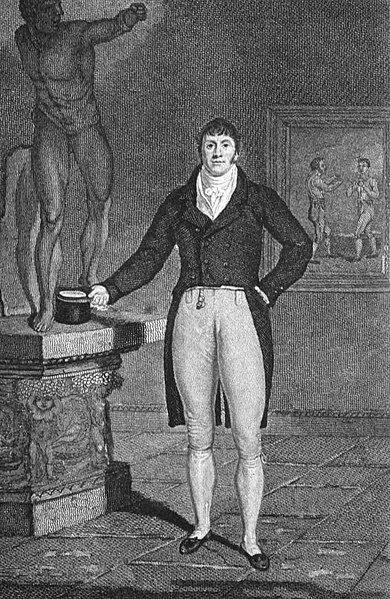

As you can imagine, there were a great many gentlemen in the Regency period, but only one man known as The Gentleman. Gentleman John Jackson was born in 1769 to a Worcestershire family of builders. He decided at age 19 to become a boxer, much against his parents’ wishes. With the awe he ultimately inspired in just about every fellow of substance, including the Prince Regent, it’s surprising to find that he only fought professionally three times, and one of those he lost. However, as the other two times he fought men who were considered top champions, he was known in his time as the heavy-weight champion of England. He held that title for one year, in 1795, after beating Daniel Mendoza—nicknamed The Jew—who had held the title the previous two years.

When Jackson retired, Thomas Owen beat all comers to gain the title in 1796, followed by Jack Bartholomew (1797 to 1800), Jem Belcher (1800 to 1803), and “Hen” Henry Pearce the Game Chicken (1803 to 1806). After Hen retired, John Gully beat all comers and reined for two years before opening his own school in London. Belcher was also known for taking on pupils.

So why was John Jackson held as the “best”?

For one thing, he appears to have been a splendid specimen of masculinity. At 5 feet 11 inches tall and 195 pounds, his body was said to be so perfectly developed (with the Regency idea of “perfection” being the statues of the Greek gods), that artists and sculptors came from all around to use him as a model. For another, he dressed well (although he favored bright colors) and spoke in cultured tones, making him the darling of the ton. His two flaws in looks were that he had a sloping forehead and ears that stuck straight out from the sides of his head. Presumably, the sculptors and artists used someone else to model the head.

Besides being the man to whom every gentleman, including Lord Byron, went for lessons, Jackson is credited with keeping the sport honest in a time when bouts were often fixed. He developed the equivalent of the Boxing Commission in the Pugilistic Club, which collected subscriptions from wealthy patrons and sponsored fights several times a year. For each fight, a Banker was appointed to hold the purse as well as many side bets that might be made. Jackson was often nominated for this position.

So great was his prestige that Jackson was called on to arrange pugilistic demonstrations for the aristocracy, including fights before the Emperor of Russia, King of Prussia, Prince of Wales, and Prince of Mecklenburg. At the 1821 coronation of George IV, Jackson furnished a group of pugilists to act as guards to keep lesser mortals at bay.

The Gentleman bowed out of this world on October 7, 1845. But he left a legacy that endures to this day.

Regina Scott is the award-winning author of more than 40 works of sweet historical romance, several of which feature Regency gentlemen who box. In her recent release, Never Kneel to a Knight, a boxer being knighted for saving the prince’s life must prove to a Society lady who is miles out of his league that their love is meant to be.

You’ll find more on Regina online at her website, on her blog, or on Facebook.

Queen Victoria’s sapphire and diamond coronet among

80 new works joining Jewellery at V&A from April 2019

From 11 April 2019, Queen Victoria’s sapphire and diamond coronet will go on permanent public display at the V&A for the first time as the centrepiece of the William and Judith Bollinger Gallery.

Queen Victoria’s sapphire and diamond coronet was acquired by the V&A in 2017, purchased through the generosity of William & Judith, and Douglas and James Bollinger as a gift to the Nation and the Commonwealth. One of Queen Victoria’s most important jewels, it was designed for her by Prince Albert in 1840 – the royal couple’s wedding year – and made by Joseph Kitching, partner at Kitching and Abud. Albert played a key role in arranging Victoria’s jewels, and he based the coronet’s design on the Saxon Rautenkranz, or circlet of rue, which runs diagonally across the coat of arms of Saxony.

In 1842, Victoria wore the newly completed coronet in a famous portrait by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, the first he painted of her. It carried the image of the young queen around the world through replicas, copies and engravings. Over twenty years later, Victoria wore the coronet instead of her crown in 1866 when she felt able to open Parliament for the first time since Albert’s death in 1861, with her crown carried on a cushion.

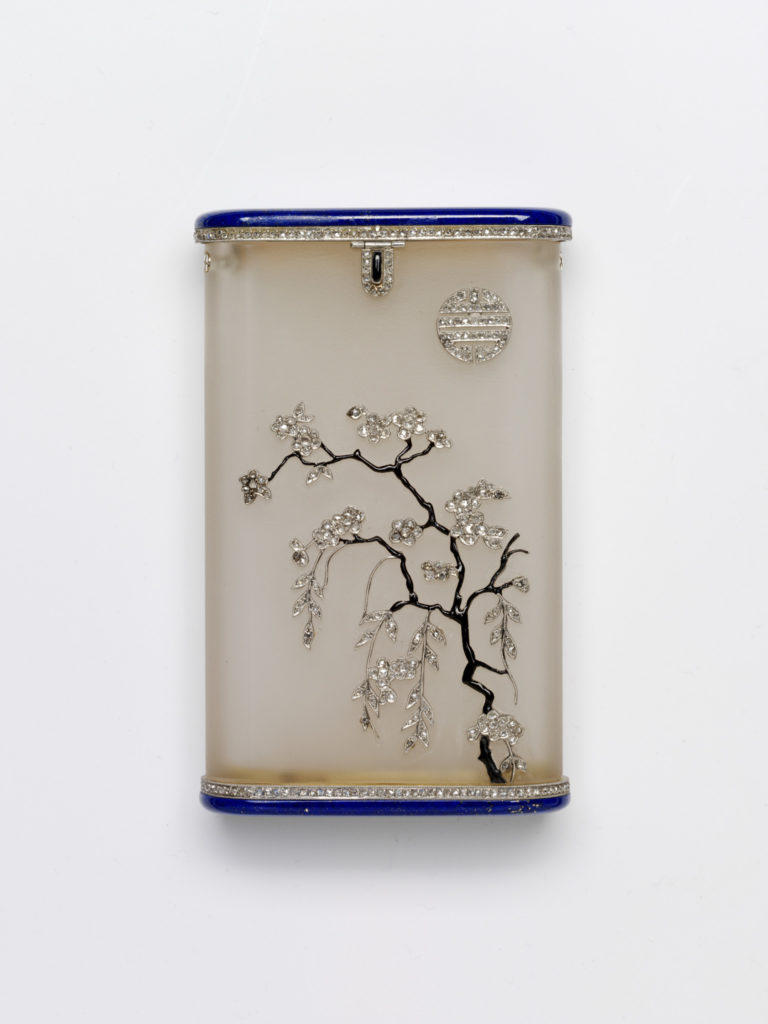

Together with the coronet, a superb collection of 49 Art Deco vanity cases will be joining the gallery as a loan and promised gift from Kashmira Bulsara in memory of her brother, Freddie Mercury. Taking inspiration from Modernism as well as Persia, Ancient Egypt, China and Japan, the cases in richly coloured hardstones, enamel and lacquer were made by, or for, Cartier, Lacloche, Van Cleef & Arpels, Charlton and other leading jewellers in Paris and New York. The collection will transform the presentation of the Art Deco period in the gallery.

Additions and new acquisitions are regularly incorporated into the display, with recent examples being Nicholas Snowman’s gift of Fabergé, and Beyoncé’s gift of a Papillon ring by Glenn Spiro. New in April 2019 will be thirty pieces ranging from the late 19th century to the present, comprising works by contemporary makers Ute Decker and Charlotte de Syllas working in Britain, Flóra Vági in Hungary, and Annamaria Zanella in Italy, among others. Pieces will include Christopher Thompson Royds’ Natura Morta necklace with poppies of gold, enamel and diamonds, Gijs Bakker’s Porsche bracelet in polyester, and a gold pendant of Paddington Bear by Cartier, created in 1975.

LOUISA CORNELL

As the weather begins to warm up here in LA (Lower Alabama) my thoughts, of course, turn to…WINTER ! Having spent three years in England in my youth and five years in Germany as a youngish adult, I have a much higher tolerance for and appreciation of cooler weather. Alabama in the Spring and Summer months moves from :

“It’s another warm one out there.”

to

“Crank up the AC, please.”

to

“It is hotter than the hinges of hell.”

to

“Tarzan couldn’t take this heat! When will it end!”

Suffice it to say, I am quite ready for Fall and Winter’s return. When the temperatures will drop into the seventies.

These days we have myriad devices available to us to adjust the temperature to a more survivable level. During the Regency Era, whilst the devices were also abundant, they were not always as efficient as today’s versions. However, some came quite close. In this post, we will explore the world of…

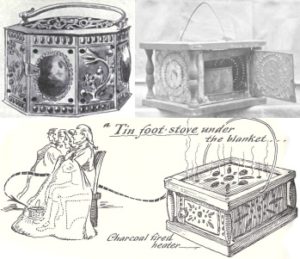

THE REGENCY FOOT WARMER

There are a number of places to research what the weather was like in England during the years of the Regency Era. One of my favorites is :

http://www.pascalbonenfant.com/18c/geography/weather.html

I like this site because, rather than give simple temperatures and basic weather information, it actually includes weather events for each year and more commentary on what the weather was like and what it was like to live through it. For instance, the winter of 1813/1814 was one of the five worst winters on record. Heavy snow fell for a number of days in January, 1814 with a brief thaw and then more snow. In short, it was cold.

Now imagine going to church in such weather. Services conducted in a large high vaulted ceiling edifice with no heat source whatsoever. Imagine the journey to said church or to a ball or to London in a carriage on less than serviceable roads. Are you feet frozen yet? Enter the foot warmer.

Foot warmers took a number of forms. The most important aspects were its size, practicality, and ease of transport. The simplest version consisted of a brick wrapped in flannel material which was placed as close as was safely possible to the fire burning in the hearths of inns and taverns. It was then placed in the carriage as it left the inn, either on the floor beneath a lady’s skirt or beneath the feet of a gentleman, perhaps with a carriage blanket draped over his legs. The brick or bricks returned to the fireplace of each inn where the carriage stopped along the way to be warmed and placed back in the carriage on departure. A simple enough device which provided heat until the absorbed warmth faded, usually long before the next coaching inn.

Most of the more advanced foot warmers were boxes of either wood, tin or brass. Each of these versions contained a metal tray at the bottom capable of being slid in and out to be filled with hot coals. Holes were poked in the sides in a regular pattern and a rope or metal handle was attached at the top for ease of portability.

An innovation brought into production during the latter part of the Regency Era and even more prevalent during the Victorian Era was the ceramic foot warmer. This device was filled with water, heated on the hearth, and placed on the carriage floor beneath a lady’s skirts. Early versions were completely round, but latter versions had a flat side, designed to stabilize the device on the floors of moving carriages.

You will notice on the one above there is a hole for the water to be poured into it. What the photo does not show is how the bottle is closed. They are usually fitted with a cork at the end of a clay piece that looks rather like the top and first several threads of a screw. I know this from personal experience as I own two of these bottles. Treasures my mother purchased at an estate sale whilst we lived in England over fifty years ago.

An interesting use made of warming pans and foot warmers during the Regency Era was as a sort of vaporizer against colds, coughs, and some forms of asthma. Below is a mention of this use in a period newspaper.

Whitehall Evening Post, December 22, 1785

At this season of the year when the excessive damps, produced from the vapours of the earth have such a visible effect on the human body generating colds and putrid disease of the most fatal kind; the following, which has been tried in the circle of a few families, would doubtless have its use if more generally adopted, as it is not only a specific preventive, but is the surest palliative in asthmatic and consumptive constitutions. When the air is thick, foggy or moist, let small lumps of pitch be thrown into your first in such degree and so frequent, as to keep up an almost constant smell of bitumen in the apartment. In rooms where fires are not frequently used, a warming pan throwing into it small lumps of the same particularly before going to bed, might be applied with conveniency. Houses newly painted are best purified in this manner, and the more so as neither injures nor soils.

It wasn’t impossible to stay warm during the Regency Era, but in many cases it took a great deal of ingenuity. And a great deal of caution. Hot coals, even in a tin box, presented a very real danger to ladies wearing skirts made of materials not known for their fire-resistant properties. There are no reports of this sort of accident occurring, but I daresay there were some close calls.

So for those ladies who have not yet met their Mr. Darcy,

Might I suggest a foot warmer? Or perhaps a pug or two?

Guest post by author Regina Scott

Welcome back to the boxing square! If you missed part one of this series, you can find it here.

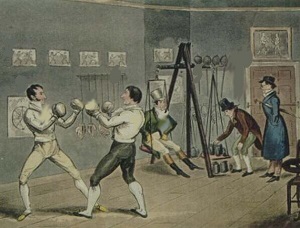

So, let’s say a gentleman became so enamored of boxing that he wanted to participate in the sport. Professional boxers were not sons of the aristocracy, but that didn’t stop the aristocracy from aping them. One of the most famous boxers of the day, Gentleman Jackson, one-time champion of England, taught boxing from his salon at No. 13 Bond Street three times a week (alternating with Angelo’s fencing school, which used the same space). Gentlemen as well known as Lord Byron came to learn from the best.

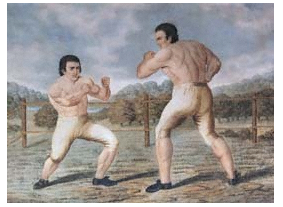

Jackson taught the “scientific style” of boxing, which included nimble footwork and the correct judging of the distance required to strike the opponent. He also advised adopting a posture of a slightly bent body, head and shoulders forward, and knees slightly bent and at ease with fists well up. He taught that fighting with the entire body (scrapping or brawling) was ineffective against the power of a well-trained fist, proving his point by having his students attempt to attack him and fending them off with fists alone.

Between sessions at being soundly beaten by the Gentleman, an aristocratic fellow might practice at home, punching at air or sparring with a friend or family member. Punching bags were not invented until later, but that doesn’t mean some resourceful individuals didn’t figure out a way to create a practice bag on their own.

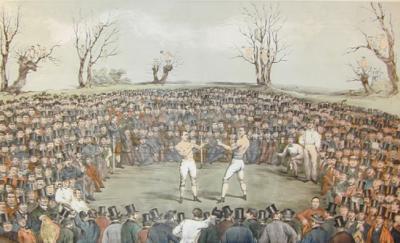

And what if a lady was enamored of the bare-chested boxers, er I mean the sport of boxing? Proper ladies were not supposed to attend boxing matches. The display of skin combined with the brutalism of the events and the unsavory crowds were deemed too much for the fair sex. Some still came in disguise or inside closed carriages, which could ring the square. Some went so far as to take boxing lessons at home. The practice was thought to provide excellent exercise.

Even if a gentleman didn’t choose to tutor under Jackson or one of the other teachers at the time, he would be sure to attend the matches. These matches were frowned upon by the magistrates. I gather it was like the saying today about hockey—I went to a boxing match and a fight broke out. One of the reasons for locating the matches just outside London on a work day was that the “riff-raff” couldn’t spare time away from work to get there, and tickets might be charged for admission.

The match itself was markedly different from what we know today. They were often held in open fields. An eight-foot square was generally roped off on the ground with stakes at each corner, although some of the larger fights were held on a raised plank floor. Each fighter had a kneeman and a bottle man, who also kept time on the rounds and breaks. The former knelt with one knee up for the boxer to sit on between rounds. The latter provided water for the boxer to drink, a sponge to wipe him down, and an orange for a quick burst of energy. Brandy was supposed to be used only for emergencies. A pair of umpires, usually former fighters themselves, kept the two boxers apart and agreed on how to deal with questionable practices like holding a man’s hair to keep him in place to be hit. A referee was only used if the two umpires could not agree.

The bouts consisted of rounds; each round lasted until at least one of the men was knocked down or thrown off his feet. A fight could run up to 50 rounds, although one before the Regency (1789) was said to hit 62 rounds. If you do the math like I did, that means someone could be hit hard enough to fall down as many as 50 times in one fight. And breaks between the rounds (after someone fell) were only 30 seconds. This was not a sport for the squeamish!

Ready to take up your tutelage at the feet of the master? Come back for the next installment, when we learn more about the Gentleman himself.

Regina Scott is the award-winning author of more than 40 works of sweet historical romance, several of which feature Regency gentlemen who box. In Never Kneel to a Knight, a boxer being knighted for saving the prince’s life must prove to a Society lady who is miles out of his league that their love is meant to be.

You’ll find more on Regina online at her website, on her blog, or on Facebook.