Guest post by author Regina Scott

Welcome back to the boxing square! If you missed part one of this series, you can find it here.

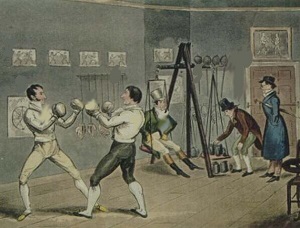

So, let’s say a gentleman became so enamored of boxing that he wanted to participate in the sport. Professional boxers were not sons of the aristocracy, but that didn’t stop the aristocracy from aping them. One of the most famous boxers of the day, Gentleman Jackson, one-time champion of England, taught boxing from his salon at No. 13 Bond Street three times a week (alternating with Angelo’s fencing school, which used the same space). Gentlemen as well known as Lord Byron came to learn from the best.

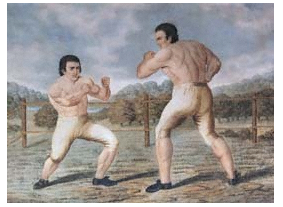

Jackson taught the “scientific style” of boxing, which included nimble footwork and the correct judging of the distance required to strike the opponent. He also advised adopting a posture of a slightly bent body, head and shoulders forward, and knees slightly bent and at ease with fists well up. He taught that fighting with the entire body (scrapping or brawling) was ineffective against the power of a well-trained fist, proving his point by having his students attempt to attack him and fending them off with fists alone.

Between sessions at being soundly beaten by the Gentleman, an aristocratic fellow might practice at home, punching at air or sparring with a friend or family member. Punching bags were not invented until later, but that doesn’t mean some resourceful individuals didn’t figure out a way to create a practice bag on their own.

And what if a lady was enamored of the bare-chested boxers, er I mean the sport of boxing? Proper ladies were not supposed to attend boxing matches. The display of skin combined with the brutalism of the events and the unsavory crowds were deemed too much for the fair sex. Some still came in disguise or inside closed carriages, which could ring the square. Some went so far as to take boxing lessons at home. The practice was thought to provide excellent exercise.

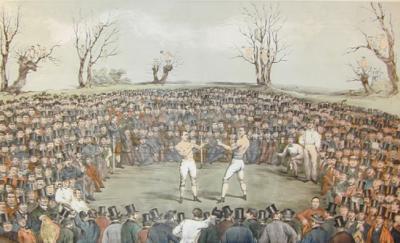

Even if a gentleman didn’t choose to tutor under Jackson or one of the other teachers at the time, he would be sure to attend the matches. These matches were frowned upon by the magistrates. I gather it was like the saying today about hockey—I went to a boxing match and a fight broke out. One of the reasons for locating the matches just outside London on a work day was that the “riff-raff” couldn’t spare time away from work to get there, and tickets might be charged for admission.

The match itself was markedly different from what we know today. They were often held in open fields. An eight-foot square was generally roped off on the ground with stakes at each corner, although some of the larger fights were held on a raised plank floor. Each fighter had a kneeman and a bottle man, who also kept time on the rounds and breaks. The former knelt with one knee up for the boxer to sit on between rounds. The latter provided water for the boxer to drink, a sponge to wipe him down, and an orange for a quick burst of energy. Brandy was supposed to be used only for emergencies. A pair of umpires, usually former fighters themselves, kept the two boxers apart and agreed on how to deal with questionable practices like holding a man’s hair to keep him in place to be hit. A referee was only used if the two umpires could not agree.

The bouts consisted of rounds; each round lasted until at least one of the men was knocked down or thrown off his feet. A fight could run up to 50 rounds, although one before the Regency (1789) was said to hit 62 rounds. If you do the math like I did, that means someone could be hit hard enough to fall down as many as 50 times in one fight. And breaks between the rounds (after someone fell) were only 30 seconds. This was not a sport for the squeamish!

Ready to take up your tutelage at the feet of the master? Come back for the next installment, when we learn more about the Gentleman himself.

Regina Scott is the award-winning author of more than 40 works of sweet historical romance, several of which feature Regency gentlemen who box. In Never Kneel to a Knight, a boxer being knighted for saving the prince’s life must prove to a Society lady who is miles out of his league that their love is meant to be.

You’ll find more on Regina online at her website, on her blog, or on Facebook.