Putting an `Upstairs, Downstairs’ spin on our Country House tour this year, Number One London Tours is offering an up-close look at six of Britain’s finest stately homes, each showcasing fabulous state and family rooms and well preserved servants’ quarters, allowing you to truly experience both worlds and to do hands-on period research. In addition, each of the houses features extensive and varied gardens, as well as domestic outbuildings such as stables, gardener’s cottages and follies.

Grade I listed Tatton Park, above, is one of the most complete estates to come under the care of the National Trust. It comprises the neo-classical mansion, extensive, award winning gardens, a working farm and a 1,000 acre deer park. The rich furnishings of the Tatton Park mansion and its important library and furniture collections reflect the growing wealth and status of the Egerton family at the end of the 18th and during the 19th centuries.

Our 2017 Country House Tour group enjoyed their visit to Tatton Park, where we spent the day exploring Upstairs –

And Downstairs –

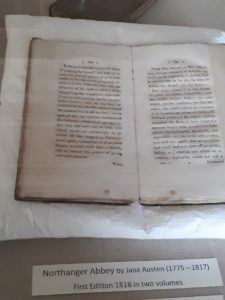

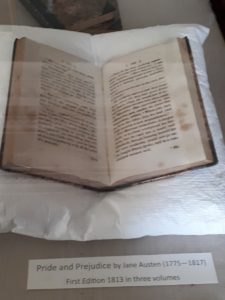

While in the library are three Jane Austen first editions –

Other houses on the 2021 Country House itinerary include

Harewood House, family seat of the Earl and Countess of Harewood and now film set, having stood in for Buckingham Palace during the filming of ITV’s Victoria. The magnificent House displays fourteen state rooms featuring the work of Robert Adam and extensive domestic rooms below stairs, all of which will be seen during our guided tour of the house. Following our tour, take some time to stroll the `Capability’ Brown landscapes, the award winning gardens and ornamental lakes.

Shugborough Hall, home to the Anson family, the Earls of Lichfield, since 1624 and a rare example of a complete estate with all major buildings surviving, including the Hall, servant’s quarters complete with kitchens and dairy , a working farm, watermill, brewery and a walled garden.

Castle Howard, one of the Treasure Houses of England, is in store for us today. Ancestral seat of the Carlisle branch of the Howard family, many will recognize it as “Brideshead” in two different film adaptations of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited and various interiors were used in filming Death Comes to Pemberley and as Kensington Palace in Victoria.

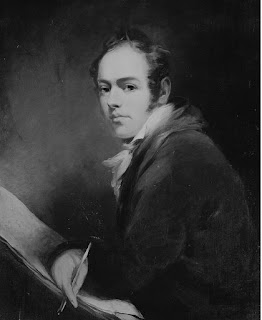

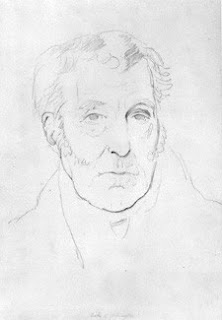

Lyme Park will include a guided tour of the house and, as a nod to the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death, an in-depth look at Lyme during the Regency period and Lyme’s very own Regency hero, Thomas Legh of Lyme. Thomas (1792-1857) was the eldest, illegitimate son of Colonel Thomas Legh of Lyme and a maid from the Vicarage near his Lancashire estate, Haydock. As a five year old, Thomas inherited Lyme and its estates – the equivalent today of around £2 million – which allowed him to travel the world.

Grade I listed Chatsworth House. The House is another location said to have served as a model for Jane Austen’s Pemberley and, since our tour will be a private one, held when the house is closed to the public, you’ll have plenty of opportunity to draw your own conclusions. Our guide will take us through the house and State Rooms, including the magnificent Painted Hall, the Sculpture Gallery and the Victorian Theatre. Home to the Dukes of Devonshire, our guide will also share with us the history of the memorable people who have left their stamp upon Chatsworth House, including the Bachelor Duke, William Cavendish, who served as Ambassador to Russia under Czar Nicholas I, Georgiana Spencer and Elizabeth Foster, two of the parties in one of history’s strangest ménage a trios, and Deborah Mitford, perhaps the most beloved of all the Devonshire Duchesses.