Kauffman was an excellent painter and did many Georgian interior medallions and other paintings — and is, in my opinion, quite underrated.

Kauffman was an excellent painter and did many Georgian interior medallions and other paintings — and is, in my opinion, quite underrated.

by Victoria Hinshaw

Tucked away in Hampshire is a stately home I have long wanted to visit for several reasons. The estate encompasses the ruins of an Augustinian priory (the title Abbey was added later — and incorrectly, according to the NT); the gardens are renowned; and Rex Whistler painted some famous trompe d’oeil decorations in the drawing room.

During the course of my research with Kristine at the various Wellington archives, we were able to steal off for the day to meet with fellow authors Alicia Rasley and Nonnie St. George. Of course the best reason for the visit was the opportunity to connect with friends from many a meeting of The Beau Monde…and fellow writers one and all. If we missed any of the relevant treasures of the estate, it was because we were so full of conversation catching up on our latest activities.

First stop was the cellarium, a remnant of the original priory building, dating from the 13th century.

The morning room was the perfect place to enjoy reading and conversing. It was a favorite spot for Maud Russell, the lady responsible for the current appearance of the estate.

In this handsome bedchamber, several remnants of the old priory building have been left uncovered.

The painting over the fireplace is Johanna Warner, Mrs. Robert of Bedhampton and her daughter, Kitty, later Mrs. Jervoise Clarke, 1736; by Joseph Highmore.

To the Right of the fireplace is another of the secret doors which show the old structure behind the walls of the current house.

The charming picture above (and below) is The Challoner Daughters by John Roger Herbert, RA (1810-1890), described as “three little girls in a woodland scene with a pony and dogs.”

The dining room was a popular venue for gatherings of the Russells’ artistic and intellectual friends in the 1930’s.

The piece d’resistance of the Montisont House: The Whistler Room. Maud Russell commissioned artist Rex Whistler to decorate her drawing room in the late 1930’s.

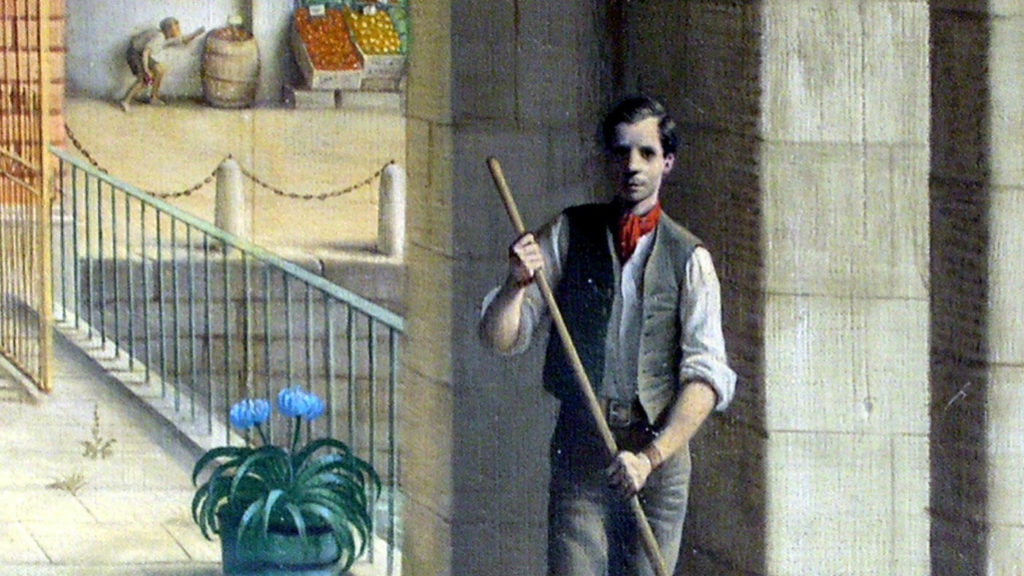

Whistler (1905-1944) painted many murals and trompe d’oeil works in England, including the famous murals in the restaurant of the Tate Britain, ad the fantasy landscape at Plas Newydd, from which the self-portrait below is a detail.

In addition to his renown as an artist, Whistler was a member of the set known as the “bright young things” between the wars, a friend not only of Mrs. Russell, but of Lady Caroline Paget, Cecil Beaton, and many others. Whistler died fighting in Normandy in 1944.

Above three pictures ©National Trust. All others in this post were taken by me.

In May, we were a little early for the roses in the NT Rose Collection of pre-20th Century species. But we thoroughly enjoyed the beautiful font (spring) and stream which feeds into the River Test, as well as the many families enjoying picnics and games on the lawns.

Would you like to experience travel in England first-hand?

Visit our website for a list of upcoming Number One London Tours.

By Victoria Hinshaw

The view above is a 1935 painting of Wilton House by Rex Whistler (1905-1944). Wilton House, near Salisbury in Wiltshire is renowned for its architecture, interiors, treasured artworks, and all the elegancies associated with the most distinguished of Britain’s stately homes. And, like some of the others, it is frequently the scene of major filming for cinema and television. The South Façade is the location of the State Apartments created by James Wyatt in the early 19th century, replacing the 17th century arrangement of rooms by Architect Inigo Jones (1573-1665) and his assistant Isaac de Caux and later altered by Webb.

Above, Wilton’s Double Cube Room plays Buckingham Palace in episodes of The Crown on Netflix. Below, it doubles for Pemberley in the 2005 version of Pride and Prejudice.

Although there is dispute over how much of the south wing of Wilton House can be attributed to Inigo Jones (1573-1652), we know that the Double Cube Room and the Single Cube Room along with the other state rooms were finished by John Webb (1611-1672) in the mid-17th century. Various changes have been made over the years, but the earls and countesses have maintained most of the magnificence designed by Jones and Webb. Below, two views of The Single Cube Room, 30x30x30 feet in dimension, a perfect cube.

The Double- and Single-Cube Rooms were part of the State Rooms in which the monarch was to visit and mingle with Lord Pembroke, his family, friends, and retainers. The Single Cube Room, below, was the first of the State Rooms and led into the Double Cube. The furniture is by Chippendale, added in the 18th century. Above, the Single Cube Room, 30 x 30 x 30 feet.

The portrait over the fireplace is Henriette de Querouaille, Countess of Pembroke, wife of Philip, 7th Earl, and sister of Louise, mistress of Charles II and mother of the 1st Duke of Richmond. The portrait was painted by Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680).

The Double Cube Room, below, is the size of two 30-foot cubes, a technique Inigo Jones used in several buildings. Much of the furniture in the two rooms is by William Kent or Thomas Chippendale.

The Double Cube Room, originally called The King’s Great Room, is sixty feet long by thirty feet wide and thirty feet high. The magnificence of the room defies description! The ceiling decoration is clearly in the baroque style.

The central ceiling panels show three views of the legend of Perseus painted by Emmanuel de Critz. The twelve-foot coving was decorated with swags, urns, and putti by Edward Pierce, a frequent collaborator with Architect Inigo Jones. They are dated c.1653

Below, the painting for which the room was designed, the magnificent family portrait, c. 1635, by Anthony Van Dyck of the 4th Earl of Pembroke and his family which hangs at one end of the Double Cube Rooms. At 17 feet wide, it is the largest portrait by Van Dyck (1599-1641) in England. Numerous other portraits by Van Dyck and his studio adorn the walls.

The State Rooms served as Allied headquarters during World War II; the D-Day landing in Normandy was planned here.

Below, the Great Ante Room, added in the 18th century, is sometimes thought of as James Wyatt’s homage to Inigo Jones.

The King’s Bed Chamber and King’s Closet were redecorated in the 18th c. for the visit of George III and Queen Charlotte in 1778. Many priceless masterworks hang on the walls.

The house is replete with great works of art in multiple media. Many members of the Herbert family, the Earls of Pembroke, were avid collectors.

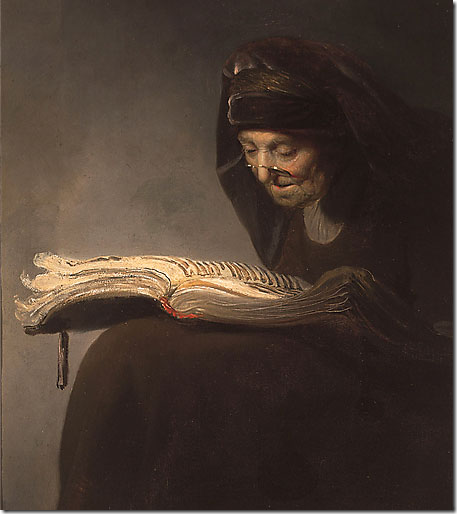

Above, Mother Reading, c. 1629, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), is one of the most famous paintings in the collection of Wilton House.

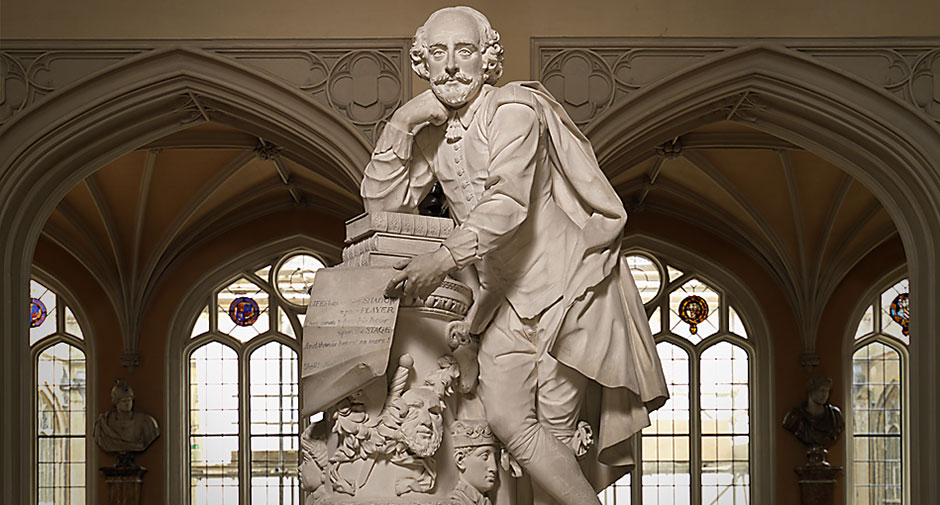

At the currently-used entrance on the North Front, visitors arrive in the Front Hall designed by James Wyatt in 1809. Who better to greet us than The Bard himself. According to the Guidebook, the statue “recalls the 2nd Earl’s and his wife Mary Sidney’s patronage of literary men and of Shakespeare above all.”

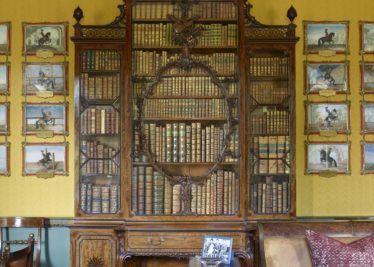

Numerous other rooms, more than one could count, are worthy of attention. I particularly liked the Large Smoking Room, redecorated by the current Lady Pembroke in 2017. The picture above was taken before the new color scheme was installed. Below is the yellow moiréed silk now on the walls. The huge bookcase, from the workshops of Chippendale, is a temptation I could hardly survive. What is tucked away inside? Imagine how much work you could get done here — once you had examined the art and furniture and gazed out the windows for a month or two!

I have visited Wilton House several times, but I will never get enough of this wonderful house and grounds…on the edge of the city of Salisbury in Wiltshire.

If you’d like to see some of England’s stately homes in person, visit our Number One London Tours site to see all of our upcoming country house tours and their itineraries.

On the edge of the city of Salisbury is one of England’s greatest country houses, the home of the Herbert family for almost five centuries. Wilton is one of those fabled British Country Houses which almost defy description. Should one concentrate on the architecture, which includes Tudor, Elizabethan, Palladian, and Regency examples? The interior, of amazing variety and stellar quality? The gardens? The collection of old master artworks? Or, how about the many stories of the history of the Herbert family, which is currently represented by William Alexander Sidney Herbert, 18th Earl of Pembroke, his Countess and their four children?

The top photo shows the North Front, dating from the Tudor era, the current public entrance to the house. Immediately above is the South Front, the wing of the house probably designed by Architect Indigo Jones in the Palladian style in the 17th century. This area contains the sumptuous state rooms.

Above, the East Front, opening into the public lawns and gardens, dating before the 16th century. This was the original entrance to the house. You can see that even today, restoration work is necessary.

The West Front and its garden are the private areas of the 18th Earl of Pembroke, his wife and four children. Below, the official portrait of William Herbert, the 18th Earl of Pembroke, and his dog painted by artist Adrian Gottlieb. ‘Will’ is the latest of the long line of owners belonging to the Herbert family,

I am sorry to report that no photography is allowed in the house so in these posts, I will be mixing ‘borrowed’ photos, of which there are many on the web, with my own pictures. First, let’s look at the exterior and the gardens. Below, an aerial shot of the house with the south façade at the left.

Below, from the central cloisters courtyard, looking east at the inside of the East Front. The original house was built on the site of an 8th-century priory. After Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, the site was ceded to Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke (of the new creation) in 1544. He constructed a house in the quadrangular style which through many remodelings, remains today with a central open courtyard.

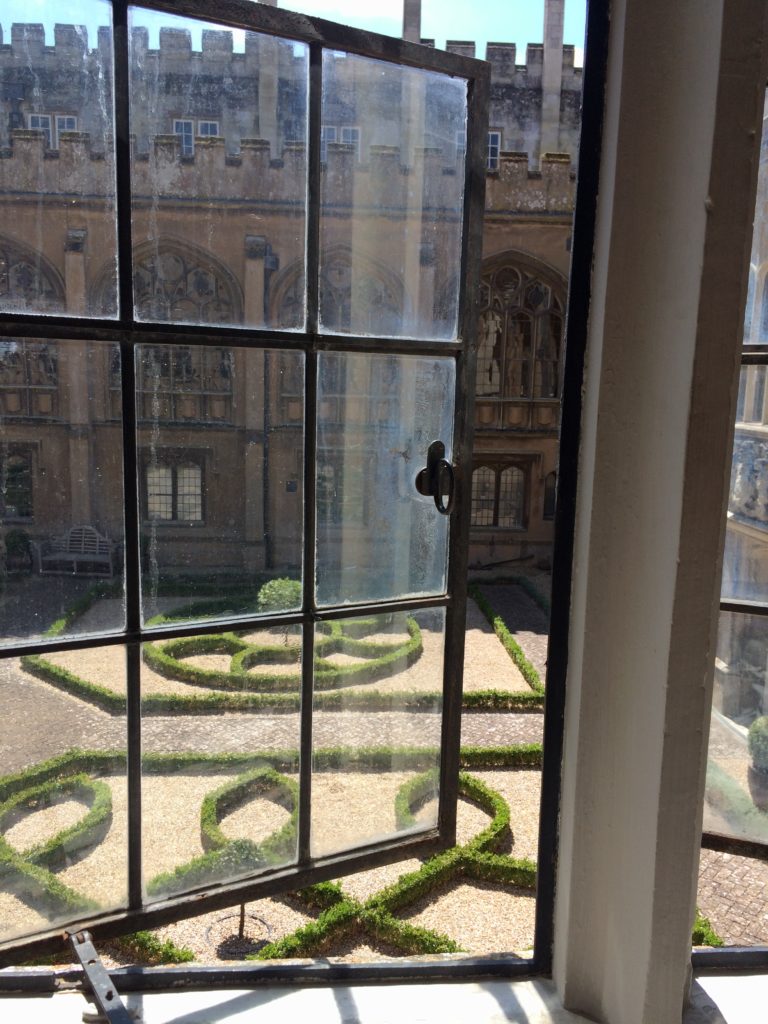

Below, peeking out from inside the cloisters, re-built by James Wyatt in 1801.

Inside the Cloisters, you will find a collection of statuary, including rare classical antiques collected by the Earls of Pembroke.

Today, visitors enter through another courtyard facing the North Front, past the fountain and a grove of trees among the patterned plantings.

Behind us was the great gate, often a symbol of Wilton House.

Leaving the interior for another post, let’s look at some of the gardens. I am particularly fond of Palladian Bridges – why I cannot imagine, but I find them charming. Below, the Wilton Palladian Bridge, constructed in 1737 by the 9th Earl of Pembroke, known as the “Architect Earl” and his assistant Roger Morris. It was designed to bridge the River Nadder in the style of the Italian architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). It has been copied at least three times, at Stowe and at Prior Park near Bath in England and at Tsarskoe Selo near St. Petersburg, Russia.

The inspiration for the Palladian Bridge is reputedly an unbuilt design for Venice’s Rialto Bridge, drawn by Andrea Palladio about 1570, pictured below in a Capriccio by Canaletto, 1742.

The river Nadder is a chalk stream known for its trout flyfishing.

Below, the charming Japanese Garden, also known as the Water Garden, with its red bridges and reflecting pools, was designed by Henry Herbert, 17th Earl of Pembroke, who died in 2003.

In Part Two, we will look at the magnificent interiors of Wilton House.

Victoria Hinshaw, here.

After two hundred fifty years, the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is celebrating its anniversary by adding an adjacent building to increase its exhibition space. The new look, not quite completed, opened May 19, 2018. I visited on May 24 and was delighted with newly added facilities. The annual Summer Exhibition will open June 12, 2018.

The newly added building once held the Museum of Mankind, located “behind” the Piccadilly site of Burlington House, home of the RA since 1868. The Museum of Mankind, an adjunct of the British Museum, moved out of the building in 2004. The RA subsequently bought it and held a competition for a design to merge the two structures. After a complicated series of setbacks, the eventual winner, architect David Chipperfield succeeded admirably. More building pictures are below, after the story of one of the opening exhibitions I enjoyed so much.

The exhibition The Making of an Artist: The Great Tradition intrigued me. As a researcher into the art and architecture of the Georgian, Regency, and Victorian periods, I was familiar with many of the early RA fellows, but had never seen the works shown, drawn from the vaults of the RA.

The huge, almost monumental painting leads the visitor into a selection of works by some of the earliest members. Lawrence, largely self-taught, studied briefly at the RA before earning fame as a portraitist and becoming a full member. He was the fourth president of the RA.

At the beginning of the exhibition, a text panel explains The Royal Academy Foundations: In 1768 a group of painters, sculptors and architects convinced King George III to support the creation of the Royal Academy of Arts. Their aim was to improve the quality of art in Britain and to raise the status of British artists and architects. The new Academy had three key functions that continue today:

Run an art school, training the next generation of artists

Hold an exhibition, selling contemporary art annually, now the Summer Exhibition

Elect as Royal Academicians a small number of leading painters, sculptors and architects (and eventually printmakers)

The full title is The Royal Academicians Assembled in their Council Chamber to Adjudge the Medals to the Successful Students in Painting, Sculpture, Architecture and Drawing. In the back row are the two female founding members, Angelika Kauffmann and Mary Moser. They were not allowed to participate in the life drawing classes.

The esteemed portraitist Joshua Reynolds was elected the first RA President.

Angelika Kauffmann, among the founding members of the Royal Academy

Angelika Kauffmann, among the founding members of the Royal Academy

Kauffmann is shown sketching the torso, one if many sculptures or copies used as models by RA members and students to hone their drawing skills. The torso, like others of its ilk, has been in the possession of the RA for 250 years. It stands nearby, seen below in two views.

Note how the light changes the hue of the photograph, according to the angle.

In the painting of the RA members above, you will see a model of the Laocoon, an ancient Greek statue used for the same purpose as the torso. The exhibition asks the question: “Does great art begin with studying nature, or studying great art of the past?” One must decide for oneself! But Reynolds considered the study of great art essential for artists.

Part Two, further adventures at the RA, coming soon.