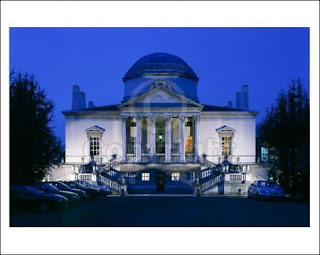

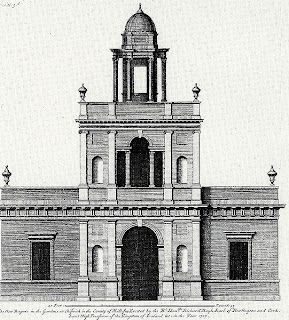

Basildon Park is in Berkshire overlooking the lovely Thames Valley, built in the 1770’s in the strict Palladian style by architect John Carr of York.

Basildon Park was abandoned about 1910 and stripped of its furnishings even including flooring, fireplace surrounds and woodwork. It was used to house troops or prisoners in both world wars. Some rooms were removed and reconstructed in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City (ballroom, below).

Basildon Park stood mostly empty and deteriorating until 1952 when Lord and Lady Iliffe, a newspaper tycoon and his wife, rescued the house. Lady Iliffe writes, “To say it was derelict is hardly good enough: no window was left intact, and most were repaired with cardboard or plywood; there was a large puddle on the Library floor, coming from the bedroom above, where a fire had just been stopped in time; walls were covered with signatures and graffiti from various occupants….It was appallingly cold and damp. And yet, there was still an atmosphere of former elegance, and a feeling of great solidity. Carr’s house was still there, damaged but basically unchanged.”

Views of the outside show the Bath stone construction. The Palladian window in the Garden Front is in the Octagon Room.

The Iliffes were fortunate enough to find genuine Carr fireplaces and woodwork removed from other houses, mostly in Yorkshire. Carr employed meticulous craftsmen and used standard measurements so that the pieces were virtually interchangeable.

Again, Lady Iliffe: “Carr was such a precise architect that his mahogany doors from Panton (in Lincolnshire) fitted exactly in the sockets of the missing Basildon ones.” Thus Basildon is both authentic and a recreation in one.

contemporary pieces, including the inevitable floral chintzes that simply drip with that country house charm. Right, the Octagon Room interior.

Upstairs the generously sized rooms were adapted to alternating bedrooms and huge bathrooms. It is a bit of a shock to see one of the perfectly proportioned rooms with its decorative plaster ceiling and elaborate woodwork and marble fireplace decked out with nothing more than the finest 1950’s plumbing fixtures.

Upstairs the generously sized rooms were adapted to alternating bedrooms and huge bathrooms. It is a bit of a shock to see one of the perfectly proportioned rooms with its decorative plaster ceiling and elaborate woodwork and marble fireplace decked out with nothing more than the finest 1950’s plumbing fixtures.

Basildon Park was built between 1776 and 1782 by Sir Francis Sykes, created a baronet in 1781. His roots were in Yorkshire and he chose Carr of York to build his house, a classical Palladian villa with a main block of rooms joined to pavilions on either side. The Sykes fortune was made during his service in India. Right is the view of the countryside.

In 1838, the Sykes family sold the house to James Morrison (d. 1857), a Liberal MP who had turned his London haberdashery business into an international concern. By the way, when he was a shopman at Todd and Co., he married his employer’s daughter, and eventually took over the firm. Morrison engaged architect John Papworth to design handkerchiefs for his company and later to remodel Basildon. Morrison had acquired a fine collection of paintings and was one of the founding fathers of the National Gallery in London. Papworth worked at Basildon from 1837 to 1842, making some changes to the Octagon Room and other interior designs, all in keeping with the original spirit of Carr’s house. Morrison’s daughter Miss

Ellen Morrison was the last resident before Basildon Park fell into disuse.

Basildon Park was used to house soldiers during World War II, as were many country houses, and certainly suffered occasional, if not constant, abuse.

Basildon Park was used to house soldiers during World War II, as were many country houses, and certainly suffered occasional, if not constant, abuse. The Iliffes were collectors of the work of the distinguished English artist Graham Sutherland, whose gigantic tapestry adorns the modernist reconstruction of the Coventry Cathedral. (The 14th century cathedral was destroyed in 1940 by German bombs; a modern cathedral was built and filled

The Iliffes were collectors of the work of the distinguished English artist Graham Sutherland, whose gigantic tapestry adorns the modernist reconstruction of the Coventry Cathedral. (The 14th century cathedral was destroyed in 1940 by German bombs; a modern cathedral was built and filled with works of contemporary art.) A number of Sutherland’s paintings and many studies for the tapestry he designed hang at Basildon. The Iliffe family presented the house to the National Trust in 1978.

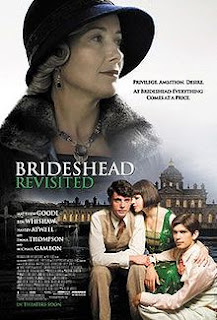

Basildon Park has often served as a set for costume dramas for the BBC and other producers. Here is a scene from the 2005 Pride and Prejudice, where Basildon enacted the role of Netherfield Park.

Basildon Park has often served as a set for costume dramas for the BBC and other producers. Here is a scene from the 2005 Pride and Prejudice, where Basildon enacted the role of Netherfield Park. This picture shows how carefully designed temporary baseboards can hide 21th century electrical outlets or cable connections.

This picture shows how carefully designed temporary baseboards can hide 21th century electrical outlets or cable connections.To Basildon Park in Berkshire now in the capable hands of the National Trust, we wish as many more rebirths as necessary to keep out the damp and bring in the tourists.