I first wrote about Vimeiro when Zebra Regency Romances published my novel Least Likely Lovers in August 2005. In the story, Major Jack Whitaker, formerly of the 22nd Foot, was severely injured in the Battle of Vimeiro, (21 August, 1808) and has come home to England to complete his recuperation, hoping to return to the front beside his comrades. However, in the meantime, Sir Arthur Wellesley (eventually to become the Duke of Wellington) has asked Jack to build support for the army among politicians and social leaders in London, an assignment that Jack finds impossibly frustrating. You won’t be surprised to find that Jack finds a lady with whom he falls in love.

The Battle of Vimeiro (also called Vimiero or Vimera) was the first major conflict of the Peninsular War, part of the greater continent-wide Napoleonic Wars. Up to Napoleon’s 1807 invasion of Portugal, Britain’s oldest ally, British participation in the European war had involved the navy, diplomacy, perhaps major scheming, but not many actual soldiers. When the Portuguese needed help, however, the government in London sent troops to oppose the French. They arrived in August 1808 under the leadership of Major General Sir Arthur Wellesley.

On a trip to Lisbon, my husband and I hired a car to take us to see the site of Battle of Vimeiro. We drove via multi-lane freeways north out of Lisbon, thinking about what a difference 200 years made in transportation. When we turned off the road, not far from Torres Vedras, we saw a primarily agricultural countryside filled with deep ravines, craggy rocks, rough pastures, and adorned with olive groves.

Armed with better directions, we drove back into the village past the large barn-like structure which was used as a hospital during the battle and the church, near which some skirmishing took place.

Armed with better directions, we drove back into the village past the large barn-like structure which was used as a hospital during the battle and the church, near which some skirmishing took place.

With one or two deft turns, we found the park on the heights with its memorial and blue tile pictures of the battle, shown here. I walked around the park, looking out at the battle site, trying to visualize the British and French troops in their colorful uniforms, to hear the explosion of artillery and rattle of musket fire. A map of the battle overlooks the countryside from the heights. But aside from the memorial park, one would never guess this peaceful place had ever seen the deaths of hundreds of men or heard cries of the wounded.

Our driver said in his more than twenty years of experience taking tourists around Portugal, no one had ever asked to come here before. Why, he asked, was I eager to find the site of the Battle of Vimeiro? When I told him about my novels, I imagined he thought of war stories filled with blood and gore. It probably never occurred to him that I write gentle stories of love and lifelong commitment. I wished that I had a copy of one of my novels to give him.

Returning to events of 1808, Major General Wellesley had landed his troops in central Portugal, with the goal of moving south to take Lisbon from the French. They fought a battle at Rolija, August 17, 1808. After several hours of brutal combat, the French were forced back. Wellesley moved on to the Maceira River, just west of Vimeiro, where more British troops came ashore with their horses and equipment.

Four days later, about 16,000 British troops and 2,000 Portuguese defeated about 19,000 French under General Jean-Andoche Junot (1771-1813) at Vimeiro. Wellesley stationed his troops on ridges between the village and the beach on the night of August 20th. By dawn, they could see the French approaching. In the face of British fire, General Junot’s men repeatedly failed to take the heights, though in various skirmishes, there was hard combat, including hand-to-hand fighting in the village. To the north of town, the French fell prey to one of Wellesley’s favorite strategies: stationing his troops out of enemy sight behind the crest of a hill, then wiping out the enemy as they came over the top.

By midday, Junot was beaten and the newly arrived British generals called an end to the firing. Wellesley advocated continuing the rout, driving the enemy out of Portugal all the way to French soil. However, as the battle had progressed, Wellesley’s overly cautious superior officers came ashore; first, General Harry Burrard (1755-1813), then General Hew Dalrymple (1750-1830). They overruled Wellesley’s plans to chase after the French. Thus, by allowing the French time to regroup and bring in reinforcements, the British lost their advantage. Instead, over Wellesley’s objections, Burrard and Dalrymple organized a conference to negotiate with the French at Cintra (aka Sintra) several days later.

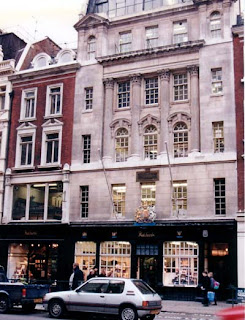

The Convention of Cintra was signed August 30, 1808, nine days after the Battle of Vimeiro. It obligated the Royal Navy to carry 26,000 French soldiers to France, with their weapons and whatever spoils they had acquired. There was no restriction against their return to fight again in Portugal. Sir Arthur Wellesley voiced his objections, but, in the end, signed the Convention. The reaction in Britain was dramatic, led by the opposition to the government and their allies in the press. Scathing articles, mocking cartoons and contemptuous speeches condemned the terms of the convention. Wellesley, along with Generals Burrard and Dalrymple, was ordered back to London. The three generals faced a hearing before a Board of Inquiry at Horseguards, beginning November 15, 1808.

After extensive deliberations, the board voted on December 22, 1808, to accept the convention. The generals were officially exonerated, but neither Burrard nor Dalrymple ever saw military action again. Unofficially, all of London knew of Wellesley’s reluctance, and most probably knew the story of how his plan to continue the battle and push the French back to Lisbon and out of Portugal forever was thwarted.

The command in Portugal was taken over by General Sir John Moore (l). Moore died after the Battle of Corunna when French commanders chased the British troops through the mountains. Six thousand British troops, including Moore, were killed in January 1809. For more details, see this blog of May 10, 2011.