_by_Thomas_Lawrence.jpg)

The French, the Prince of Wales, gunfire, political upheaval . . . really, you’d have thought the Duke of Wellington had enough on his plate, but more often than not it was left to His Grace to attend to a hundred myriad details each week regarding the military, politics, his social and his family life. Everyone turned to the Duke of Wellington for assistance and perhaps this was at least in part because he was so good at seeing to the details of a thing, as evidenced in the thread of dispatches below that deal with shoes for both human and horse. As we read, it becomes evident that Wellington had a knack for looking at a problem from every angle and for finding it’s most expedient solution. He always offered explanation and gave the whys and wherefores behind his requests in order to stress the practicalities surrounding them. Unfortunately, not everyone at the war office was as efficient, or as concerned about the day to day running of a vast army who traveled both on their stomachs and their feet.

The Dispatches of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington:

To the Earl of Liverpool. Cartaxo, 7th Dec. 1810.

I enclose a return of the number of men and horses required to complete the regiments of British cavalry in this country. As the appointments of the heavy cavalry are so much more weighty than those of the light dragoons, and the larger horses of the former are with difficulty kept in condition, it would have been desirable to have a larger proportion of the light dragoons, or hussars, with this army; but as the officers, the men, and their horses, are now accustomed to the food they receive, and to the climate, I do not recommend that the regiments should be changed, or that any additional regiments should be sent out, excepting possibly the remaining 2 squadrons of the 3d hussars, K.G.L., of which 2 squadrons are already at Cadiz.

Your Lordship will observe that nearly 1000 horses are wanting to complete the several regiments to the number of men they now have, and 1460 to complete to their several establishments. I would recommend that no horses should be sent for service to this country which will not be 6 years old in May; and that mares should be sent in preference to horses, as it has been found that they bear the work better than the horses.

I also beg leave to recommend that about 50 or 60 horses or mares of a superior description should be purchased, at the price of £40 or £50 each, as a remount for the officers of the cavalry, who cannot find horses in the Peninsula at present fit for this service, and would pay this price for these horses.

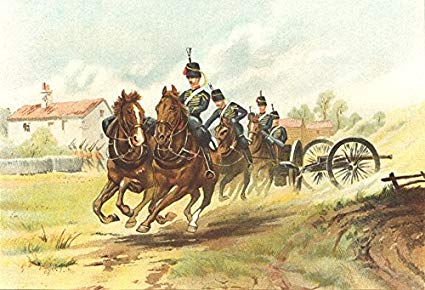

As great difficulty has been experienced in making shoes and shoe nails for the horses of the cavalry by their farriers, particularly after the cavalry have been actively employed for any length of time, and many horses have been consequently lost, I recommend that 4000 sets of horse shoes, and a double proportion of horse shoe nails, should be sent to the Commissary Gen. for the use of the cavalry, of the same description with those provided for the horses of the Royal artillery. The regiments to which these shoes would be issued would of course pay for them.

A year after Wellington had done with horse shoes, it appears he turned his pen to the matter of shoes for his troops –

Selections from the Dispatches and General Orders of Field Marshall the Duke of Wellington –

To the Earl of Liverpool. Celorico, 31st March, 1811.

The demand for shoes increases to such a degree that it is desirable that 150,000 pairs should be sent to the Tagus as soon as it may be practicable. It is very desirable that the shoes sent to the army should be of the best quality for wear, and should be made of the largest size.

The destruction of this necessary article to a soldier is very much increased by the bad quality of the shoes sent out, and by their being in general too small: and as the operations of the army have now been removed to a distance from Lisbon, the inconvenience and difficulty of supplying their consumption are much increased; at the same time, that, as the soldiers pay for the shoes they receive, it is but just towards them that they should be of the best quality for their purpose, and should fit them.’

The destruction of this necessary article to a soldier is very much increased by the bad quality of the shoes sent out, and by their being in general too small: and as the operations of the army have now been removed to a distance from Lisbon, the inconvenience and difficulty of supplying their consumption are much increased; at the same time, that, as the soldiers pay for the shoes they receive, it is but just towards them that they should be of the best quality for their purpose, and should fit them.’

And yet another missive on the same subject:

A Memoir of Field-Marshal, the Duke of Wellington: with Interspersed Notices … By John Marius Wilson

“We are sadly in want of shoes, and the carts upon the road from Lisbon to Coimbra have been so ill used that I fear we cannot depend upon the communication; and if we could, I believe we should receive them sooner by sea. It will require 40 carts to bring up 20,000 pairs of shoes, which we want; and I shall be very much obliged to you if you will ask the Admiral to allow one of his ships of war to take them on board, and bring them as soon as possible to the mouth of the Mondego.”

And on arriving at Coimbra with the army, and finding there only 6,000 pairs of shoes, the Duke of Wellington felt obliged to issue general orders for economizing the distribution of them, and to write to Lord Castlereagh begging that a further supply of 30,000 pairs might speedily be sent to Lisbon, and that, at the same time, large supplies might be sent of biscuit, oats, and hay.

Supplementary Despatches and Memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur, Duke of Wellington, Freneda, 30th Nov., 1812 –

1. The Commander of the Forces has directed that those non-commissioned officers and soldiers of the infantry and artillery who were present at the siege of Burgos, and those who were present with their regiments in Spain between the 15th and 19th November, as well Portuguese as English, shall receive a pair of shoes gratis from the Commissary.

2. The officers commanding regiments will accordingly make requisitions for these shoes.

3. Many soldiers are probably already provided with the required quantity of shoes. The officers commanding regiments will make a list of the names of these soldiers, and will have this list lodged with the Paymaster-General, in satisfaction of the demand of the Commissary-General for as many pairs of shoes last delivered to the regiment as there will be names in the list.

4. The soldiers whose names will be in these lists are not to be charged for a pair of shoes each man last received by them from the Commissary, in their accounts with the Captain of their company.

5. Of course the requisitions for shoes under this order are not to include the names of those who will be included in the lists adverted to in Nos. 3 and 4.

6. The shoes which will be required under these orders will be delivered between this time and the 1st February next.

And next it appears that the Duke had at some point been sent the wrong kind of shoes, adding to his level of frustration:

To Earl Bathurst, Lesaca, 23rd August, 1813.

My Dear Lord,

——– has sent me several pairs of his shoes, which I have endeavored to prevail upon him to desist from sending me, in terms not to mortify him. They are, in fact, of no use whatever. Those who travel on foot in this country do not wear shoes of that description. The Basques and Navarrois, and even some of the Castillians, wear sandals. The shoes worn by the common people, who do wear shoes, are made of brown leather. A man who should have on his feet, or in his possession, a pair of such shoes would be suspected immediately. They are, besides, too small for any common man. They are really quite useless, and it is better that no more should be sent.

Later in life, the Duke turned his great attention to detail upon the health and welfare of his friends and family. In the case of Miss Angela Burdett-Coutts, matters again turned to shoes. In Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Byrdett-Coutts author Edna Healey tells us that Wellington wrote to Angela:

`Don’t forget you are to leave a pair of your shoes for me that I may have some galoshes made for you. I am in earnest with this; you like walking and appear not to mind much in which state of streets you go out in . . . all that I care about is that you must be kept dry when you go out into the wet streets.’

A pair of the Duke’s own gutta-percha galoshes are preserved at Stratfield-Saye. And in order to round out our piece on Wellington and shoes, here’s a link to an ad in a 1944 issue of Life Magazine featuring the Duke of Wellington.

_by_Thomas_Lawrence.jpg)