Akin to the group paintings of the Sharps, Gores, Impeys, and Queen Charlotte’s family, is Zoffany’s cluttered-with-many-many-bodies iconic painting of the founding members of the Royal Academy – a painting faithfully reproduced whenever a piece about that august association is published – showing the two female founders, Mary Moser (a painter of exquisite still life, mostly flowers in vases) and Angelika Kauffmann (a renowned allegory painter whose work can be seen on ceilings at the Royal Academy building at Piccadilly Circus).They are on the wall, not 100% part of this mostly male group.

The painting brutally conveys the message that no women were allowed to pursue life studies, paintings using nude male models.While the men are intently engaged upon the muscular attributes of these young and muscular men, these women are framed in portraits on the wall, woefully gazing at each other, far removed from the action below.

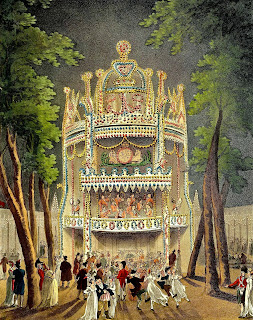

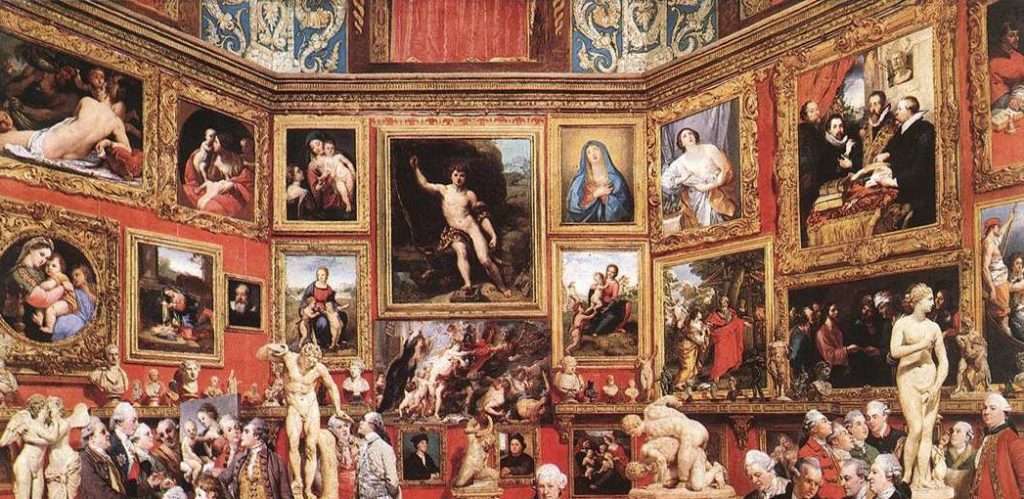

I was quite familiar with the RA painting, as I have been doing research on 18th century female painters for some years, but I had not had the opportunity to see in full force the magnificence of his famous Tribuna Of The Uffizi, painted over the years 1772-78, when Zoffany resided in Italy.The Tribuna is an octagonal room in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence that was designed for the De Medicis in the late 1580s, and where the most important collections of that family were displayed. Zoffany here portrays the northeast section of the room, but varies their arrangement – artistic license – deliberately adding works that were not normally displayed there.

This is a fabulous work, simply fabulous! My initial assessment of Zoffany’s work was now seriously challenged as I gazed upon this wonder.So much is taking place: connoisseurs discussing a nude painting; young men on their Grand Tour gazing appreciatively and lustfully at the buttocks of a marble statue of Venus; a youth eying the sketch a gentleman is making of another marble statue; and, everywhere, exquisite renderings of great works of art.One could never tire of looking at so many minute details and musing upon the vignettes told so amusingly by the artist.

As Alastair Sooke described it in the Telegraph:

“Part of the fun comes from spotting works of art (a Raphael Madonna here, a nude by Titian there), almost in the manner of the Where’s Wally? children’s books. But as well as being learned, the painting is full of hearty innuendo, as Zoffany satirises the less-than-lofty aspirations of the English ‘milordi’ who set off on the Grand Tour in search of amatory, not artistic, conquests. A group of five men gaze adoringly at the sculpted bottom of the Medici Venus (one uses an eyeglass to get a really good look). Elsewhere, there are visual gags about buggery. The work is a wonderful reminder that the 18th century was as rowdy as it was refined. Perhaps this explains why Zoffany’s royal patron wasn’t enamoured with the finished piece, which was relegated to Kew Palace.”

Sooke’s well-written, almost poetic piece (“rhythms ripple across the retina”) segues into my what-I-didn’t-know-about-Johann-Zoffany story quite nicely.The buggery jokes… !The gentleman who has his hand on the canvas of the Venus of Urbino, by Titian, and seems to be pointing to the statue of the naked wrestlers, is one Thomas Patch, a scoundrel who’d been exiled from Rome for homosexuality/aka/buggery.(This depiction of Patch, in particular, seemed to have offended Queen Charlotte, the “royal patron”; she and her husband the King can be said to have had a limited sense of humor.)

So, then, Zoffany was not as boring as his court/society/family portraits might have indicated.Indeed, he was an urbane, witty man who was involved in his share of scandal…befitting the 18th century, that great age for scandal. As Sooke comments further, he “was an urbane chap with an eye for the ladies and an appetite for the finer things in life.”How true, how true, is this last comment!

This intrigued me greatly, so I looked into it further, consulting the excellent 2011 biography by Mary Webster (Yale University Press 2011).Zoffany had married Maria Juliana Antonetta Eiselein in Wurzberg, Germany, and had moved to London with him. Claiming homesickness, she left him early on, before 1771, but then returned briefly, only to leave him again around 1772, with the same complaint of missing her family and country.

Though Mrs Papendieck’s memoirs were later disputed as to their veracity by the Zoffany’s children and grandchildren, what she has to say is fascinating. According to the 2011 book edited by Martin Postle:

“Mary Thomas, the daughter of a London glove maker, first met Zoffany sometime in the winter of 1771 or early the following year. [This would be about the time Maria Juliana Antonetta fled London for Germany the second time.] Mary’s own account of her life with Zoffany was recorded in the memoirs of her friend Charlotte Papiendieck. According to Mrs Papendieck, Mary had told her how Zoffany, who ‘in his leisure hours prowled around for victims of self-gratification’, had stalked her to her parents’ ‘humble dwelling’. Shortly afterwards, he left for Italy. On discovering that she was pregnant, Mary stowed away on the boat, making herself known to Zoffany during the voyage. On arrival in Italy, Zoffany apparently told Mary his German wife had died a few months earlier, and so ‘he married the object of his affection, who became a mother at 16’.”

“In Webster’s biography, there is some discussion as to whether she might have been 14 at the time she became pregnant. She could also have been closer to 17, but there is no definitive proof to corroborate this. She may indeed have become a mother at 16.He was 39, a good 20+ years older than she.(If she was really 14, it would have been a difference of 25 years in age!)

Mary Thomas gave birth to Zoffany’s first child we know of, a boy, in Italy.Zoffany may have gone through a form of marriage with her in Genoa that the girl thought was legal – she was very young and said to be rather naïve and shy – and he supposedly told her his wife had died – but the first Mrs Z was very much alive in 1772.(She died in Germany in 1805, 33 years later.) From 1772 onwards, however, Mary Thomas was to pass as Zoffany’s wife.

Tragedy struck when the baby was 16 months old and he fell from a go-cart down a steep set of stairs in Florence; the severe head injury was to kill him three weeks later. They went on to have four daughters together, two before he left for India in 1783 – without Mary – and two more daughters after he returned to her.

While in India, he was reputed to have taken up with an Indian woman and had at least one child, perhaps more.According to the Postle book, “Given his own libidinous predisposition, it was inevitable that he should have taken an Indian mistress, with whom he had several children, including a son.”Though it is hard to establish that he had “several children”, there seems to be agreement that he did have at least one son with his Indian mistress. This child was said to have been left in the household of a French nawab, Claude Martin, a man with whom Zoffany had been very friendly, but the little boy has been lost in the mists of time.Nothing more was ever heard of him again, nor of any other children he might have sired with this Indian woman.

Zoffany returned quite wealthy to England in 1788 after his sojourn in India and settled into that very nice home on Strand-on-the-Green. But, according to that old gossip and gadabout, diarist/letter-writer Horace Walpole, he came back “in more wealth than health”.India’s climate was harsh on Europeans, and diseases — before the advent of antibiotics – caused the deaths of many expatriates. But although he was said to be weakened in health, Zoffany lived for 22 more years. It was at 65 Strand-on-the-Green, that beautiful home on the river, where he died.

I’m standing by his tomb at the head of this piece, and here are more photographs from that churchyard many of you might have passed on the way to Kew Gardens:

I can’t identify the grandchild, nor the year of her death, nor whose daughter she was, which child of his four daughters’ children.(As I mentioned previously, there were four daughters of his marriage with Mary Thomas and a boy who died before the age of two years whose name I could not verify.)

The first two girls Zoffany had with Mary Thomas were Maria Theresa (1774), who was called Theresa, and Cecelia (1779); the last two were Claudina (1794) and Laura (1796). Their father left them ample dowries of £2,000 each and all made “good” marriages. To his wife Mary he left the house on Strand-on-the-Green and money for her upkeep.But there was a restriction on the house:she would lose it if she remarried.Though she received at least one known proposal – from the wealthy sculptor Joseph Nollekens — she never did remarry.

And what of that first wife moldering away in Germany?She passed away in January of 1805, so that bigamist Zoffany finally wed Mary Thomas at St Pancras Church on April 20th, four months after receiving word of his first wife’s death. Zoffany was 72; she was by then probably in her late 40s. They were to be legally wed only five years; the painter, who suffered from severe dementia in his last years of life, passed away in 1810.Mary Thomas outlived him by 22 years, dying in 1832 from the great cholera epidemic in London; sadly, their eldest daughter Theresa died within a few days of her mother from the same outbreak of disease.

Quite a life our peripatetic Johann Zoffany led…

One would hardly have known it, from his (mostly) sedate paintings.And he was a fun fellow, too.This painting shocked me, but only because it was the Zoffany I had not known, a man who hung condoms on his wall and dressed as a friar to take part in a bacchanalia one can only imagine!

I leave you with the bon vivant, in this later, rather happy, self-portrait, painted when Zoffany was 43 years of age…and already, alas, losing his hair:

By this time, Peter Mark Roget, almost 40 years of age and unmarried, had a thriving medical practice and had become a member of the Royal Society; he was the one called to his uncle’s bedside. Sir Samuel had slashed his throat with a razor, inconsolable after the death of his wife, whom Roget had attended in her last, fatal, illness. (This incident is described in tragic detail in the opening pages of the Kendall biography.Sir Samuel’s demise was a great loss to his family and to the nation. A good part of the blame for his suicide, alas, was attributed later to the insensitivity of the medical treatment of his nephew, Peter Mark Roget. This blame, unfortunately, may well have been warranted.Kendall states “no one questioned Roget’s concern for his uncle” but “a consensus emerged that he had failed to grasp the full extent of Romilly’s emotional agony” upon the loss of his wife. But, again, severe depression ran in the Romilly family, and perhaps no physician could – at that time – have done anything to alleviate Roget’s uncle’s grief and deterred him from suicide.

By this time, Peter Mark Roget, almost 40 years of age and unmarried, had a thriving medical practice and had become a member of the Royal Society; he was the one called to his uncle’s bedside. Sir Samuel had slashed his throat with a razor, inconsolable after the death of his wife, whom Roget had attended in her last, fatal, illness. (This incident is described in tragic detail in the opening pages of the Kendall biography.Sir Samuel’s demise was a great loss to his family and to the nation. A good part of the blame for his suicide, alas, was attributed later to the insensitivity of the medical treatment of his nephew, Peter Mark Roget. This blame, unfortunately, may well have been warranted.Kendall states “no one questioned Roget’s concern for his uncle” but “a consensus emerged that he had failed to grasp the full extent of Romilly’s emotional agony” upon the loss of his wife. But, again, severe depression ran in the Romilly family, and perhaps no physician could – at that time – have done anything to alleviate Roget’s uncle’s grief and deterred him from suicide.