In our ongoing effort to bring to light some of the most unique ladies England has ever produced, we now introduce you to Lady Cork, about whom there appeared a story in the July – December 1903 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine:

In our ongoing effort to bring to light some of the most unique ladies England has ever produced, we now introduce you to Lady Cork, about whom there appeared a story in the July – December 1903 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine:

AN ECCENTRIC LEADER OF SOCIETY

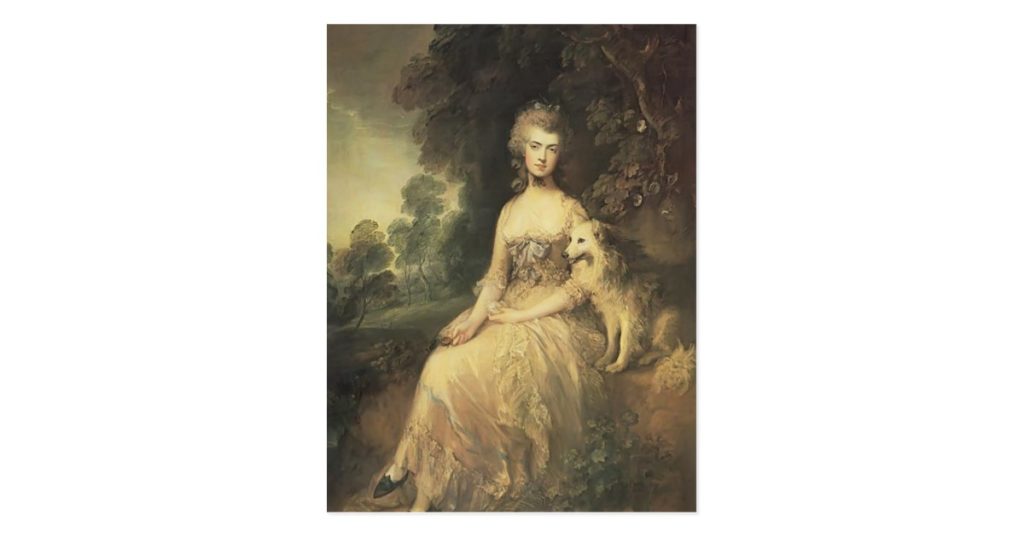

“THERE are some women who are born for society. It is quite impossible for them to lead a quiet domestic life; excitement is as the breath of their nostrils, they must alway be agitating something, or organizing something, so as to be before the public gaze. In their youth they exhibit themselves, in middle life they exhibit other people, and act as show-women to celebrities of all kinds. Such a woman was the Hon. Maria Monckton, afterwards Countess of Cork and Orrery, who was compared by the great wit, Luttrell, to a shuttlecock, `all cork and feathers.’ Even in her girlhood she was a leader of society, and at her mother’s (Lady Galway’s) house in Charles Street, Berkeley Square, she received Johnson, Goldsmith, Burke, and all the wits of the day. She belonged to Mrs. Montagu’s Blue-stocking Club, and was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, in a garden, with a dog at her feet.”

It seems that the future Lady Cork’s appearances at balls and masquerades were often mentioned in the press of the day. In the month of February, 1770, when the Wilkes riots were going on, a certain Mrs. Comely gave a masquerade at her house, in Soho, and among the motley crew Miss Monckton was prominent, as an Indian Sultana “in a robe of cloth of gold and a rich veil. The seams of her habit were embroidered with precious stones, and she had a magnificent cluster of diamonds on her head. Her jewels on this occasion were valued at 30,000/. and she was attended by four black female slaves.”

Strangely enough, in the Daily Advertiser of the same year, but of a later date (May 7th), a mysterious paragraph appeared announcing that a ” lady of high degree would appear at the Soho Masquerade as an Indian Princess, with pearls and diamonds to the price of £ 100,000, her train to be supported by three black female slaves, and a canopy to be held over her head by four black male slaves. To be a fine sight.” Whether this paragraph was in ridicule of Miss Monckton, or put in by some one desirous of emulating her, does not appear.

At this time she was twenty-three, for she was born in 1747. She was generally known as Johnson’s ” little dunce.” Boswell relates how she came by this name. He says that Johnson “did not think himself too grave even for the lively Miss Monckton, who used to have the finest bit of blue at the house of her mother, Lady Galway.” Her vivacity enchanted the sage, they used to talk together with all imaginable ease. One evening, she insisted that some of Sterne’s writings were very pathetic. Johnson bluntly denied it. “I am sure,” she said,” they have affected me.” “Why,” said Johnson, smiling and rolling himself about, “that is because, dearest, you are a dunce!”

That was supposed to settle the question, but few people would not now allow that Miss Monckton was right, and that the sapient doctor was wrong. When she mentioned his speech to him afterwards, he replied, “Madam, if I had thought so, I certainly should not have said it.” But, all the same, the name “little dunce ” stuck to her.

It was at Brighton, or Brighthelmstone, as it was then called, that Fanny Burney (at left) first made Miss Monckton’s acquaintance. In her diary for November 10, 1782, Burney notes that the day brings in a new person, the Hon. Miss Monckton, “who is here with her mother, the Dowager Lady Galway. She is one of those who stand foremost in collecting all extraordinary and curious people to her London conversaziones, which, like those of Mrs. Vesey, mix the rank and literature and exclude all beside.”

Miss Monckton, who had sent messages as to her desire to meet Mrs. Thrale and the author of “Evelina,” at length paid her visit, and is thus described by Fanny Burney’s lively and graphic pen : “Miss Monckton is between thirty and forty, very short, very fat, but handsome, splendidly and fantastically dressed, rouged, but not unbecomingly so, yet evidently and palpably desirous of gaining notice and admiration. She has an easy levity in her air, manner, and discourse, that speak all within to be comfortable, and her rage of seeing anything curious may be satisfied, if she pleases, by looking in a mirror.”

Miss Monckton, with all her oddities, must have been very good company—she was full of brightness and “go,” she had been at the court of Marie Antoinette, and did not know the meaning of the word stiffness. When Fanny Burney returned to London she went with the Thrales to a conversazione at the “noble house” in Charles Street, and relates her experiences in her own inimitable way :

” There was not much company, for we were very early. Lady Galway sat at the side of the fire, and received nobody. She seems very old, and was dressed with a little white round cap, and not a single hair, no cushion, roll, nor anything else but the little round cap, which was flat on her forehead. Such part of the company as already knew her made their compliments to her where she sat, and the rest were never taken up to her, but belonged solely to Miss Monckton, whose own manner of receiving her guests was scarce more laborious, for she kept her seat when they entered, and only turned round her head to nod it, and say ‘How do you do ?’ As soon, however, as she perceived Mrs. and Miss Thrale, she rose to welcome them, contrary to her usual custom, merely because it was their first visit. . . . ”

Miss Burney continues by saying that the company were dressed with more brilliancy than at any rout she was ever at, as most of them were going on to the Duchess of Cumberland’s.

“At the sound of Burke’s voice, Miss Monckton started up, and cried out, ‘ Oh, it’s Mr. Burke!’ and she ran to him with as much joy as, if it had been in our house, I should. Cause the second for liking her better.” Many stately compliments were paid to Miss Burney by Burke on the subject of her novel “Cecilia,” which had just been published, and she was lionised and stared at by all the fashionable guests. Finally, Sir Joshua Reynolds wanted to see her home, and Miss Monckton pressed her to come to another conversazione, when she would meet Mrs. Siddons. This invitation was duly accepted, but after that we hear no more of Miss Monckton, who, two years afterwards, in May 1786, married Edmund, seventh Earl of Cork and Orrery. His first marriage had been dissolved in 1782, and caused much scandal to the censorious public. He only survived his second marriage with Miss Monckton twelve years, dying in November, 1798.

From her widowhood dates a new period of Lady Cork’s sway as leader of society; her house, which had been the rallying-place for all the old wits, was now thrown open to the rising stars, and her salons were crowded by all the celebrities of the Regency, and even up to the early Victorian epoch.

She always signed herself “M. Cork and Orrery.” Some furniture in the window of an upholsterer having chanced to catch her eye, she wrote to him to send it to her, signing herself as usual. His answer was: “D. B. not having any dealings with ‘M. Cork and Orrery, begs to have a more explicit order, finding that the house is not known in the trade.”

Her craze for producing oddities at her parties was so great that hearing that the celebrated surgeon, Sir Anthony Carlisle, had dissected and preserved the female dwarf, Cochinie, she was immediately seized with a desire to exhibit the curiosity at one of her assemblies, and eagerly inquired, “Would it do for a lion for tonight?”—”I think, hardly,” was the answer.—”But surely it would if it is in spirits.” The term “Lion” was used for every human set piece Lady Cork meant to present at her evening entertainments. Off posted Lady Cork to Sir Anthony’s house. He was not at home, and the following conversation passed between Lady Cork and the servant.

Servant: “There’s no child here, madam.” Lady Cork: ” But I mean the child in the bottle.” Servant: “Oh, this is not the place where we bottle the children, madam, that’s at the master’s workshop.”

Lady Cork was thoroughly modern in her way of arranging her rooms at her house in New Burlington Street. A brilliant boudoir terminated in a sombre conservatory, where eternal twilight fell on fountains of rose water, “that never dry, and on beds of flowers that never fade.” Lady Clementina Davies says that “this boudoir was literally filled with flowers and large looking-glasses, which reached from the top to the bottom. At the base was a brass railing, within which were flowers, which had a very pretty effect.”

Lady Cork was very fond of wearing white—her favourite outdoor costume was a white crape cottage bonnet and a white satin shawl, trimmed with the finest point lace. She was never seen in a cap, though she lived to be over ninety. Her complexion was wonderfully pink and white, not put on, but her own, though this does not agree with Fanny Burney’s account, which describes her as being rouged, even in her comparatively youthful days. Talking of her conversaziones, she used to say:

” My dear, I have pink for the exclusives, blue for the literary, grey for the religious, at which Kitty Bermingham, the saint, presides. I have them all in their turns; then I have one party of all sorts, but I have no colour for it.”

We have already seen how Fanny Burney in the zenith of her fame was received by Miss Monckton. Now another authoress, Lady Morgan, gives, in her “Book of the Boudoir,” a very amusing account of how she was made a lioness of by Lady Cork. On this momentous evening she was only Sydney Owenson, just beginning to come into public notice as the authoress of “The Wild Irish Girl.” She relates how she ascended the marble staircase, with its gilt balustrades, her heart beating all the while with trepidation. She was wearing the same white muslin frock and flower that she had worn some nights before when she was dancing jigs with the Prince of Breffni in a remote corner of Ireland. Her black curly hair was, as usual, cut in a crop, and her brilliant black eyes shone with even more than their accustomed lustre.

She was met at the door by Lady Cork, all kindness and anxiety to show her off to the company. The whole description is so inimitable that it is best to give it in Lady Morgan’s own words :

“‘ What! No harp, Glorvina ?’ said her ladyship.

‘”Oh, Lady Cork!’

“‘ Oh, Lady Fiddlestick, you are a fool, child—you don’t know your own interests. Here, James, William, Thomas, send one of the chairmen to Stanhope Street, for Miss Owenson’s harp !’

“Led on by Dr. Johnson’s celebrated little dunce,” says ‘ The Wild Irish Girl,’ “I was at once merged in that crowd of elegants and gallants.” (Among the crowd, by the way, was a strikingly sullen-looking handsome creature, the soon-to-be celebrated Lord Byron.) “I found myself suddenly pounced down upon a sort of rustic seat by Lady Cork. … So there I sat, the lioness of the evening, exhibited and shown like the beautiful hyena that never was tamed, looking about as wild, and feeling quite as savage. Presenting me to each and all of the splendid crowd which an idle curiosity had gathered round us, Lady Cork prefaced every introduction with a little exordium,’ Lord Erskine, this is the ‘Wild Irish Girl,’ whom you are so anxious to know; I assure you she talks quite as well as she writes. Now, my dear, do tell Lord Erskine some of those Irish stories that you told the other evening at Lady Charleville’s. Fancy yourself en petit comiti, and take off the Irish brogue. Mrs. Abington says you would make a famous actress, she does indeed. This is the Duchess of St. Albans— she has your ‘Wild Irish Girl’ by heart. Where is Sheridan? Do, my dear Mr. T. (this is Mr. T., my dear, geniuses should know each other), do, my dear Mr. T., find me Mr. Sheridan. Oh, here he is. What! you know each other already ? Tant mieux. Mr. Lewis, do come forward. This is Monk Lewis, my dear, of whom you have heard so much, but you must not read his works, they are very naughty. . . . Do see, somebody, if Mr. Kemble and Mrs. Siddons are come yet! And pray tell us the scene at the Irish baronet’s in the rebellion, that you told the Ladies of Llangollen. . . . And then give us your bluestocking dinner at Sir R. Phillips’s, and describe us the Irish priests. . . .'”

Towards the end of the evening, Kemble did appear, and his remark to the Irish siren was, “Little girl, where did you buy your wig?” Being assured that her hair grew on her head, he next drew forth a copy of “The Wild Irish Girl ” from his pocket, and asked the little authoress why she wrote such nonsense, and where she got all the hard words? She promptly replied, “Out of Johnson’s dictionary.” Her epitome of the evening was as follows : “I can only say that this engouement (she means Lady Cork’s passion for exhibiting lions), indulged perhaps a little too much at my expense, has been followed up by nearly twenty years of unswerving kindness and hospitality.”

Mrs. Opie relates how she went to an assembly at Lady Cork’s in June 1814, at which Blucher, the Prussian general, then one of the lions of London society, was expected. The company, which included Lord Limerick, Lord and Lady Carysfort, James Smith of the ” Rejected Addresses,” and Monk Lewis, waited and waited, but no Blucher appeared. To keep up Lady Cork’s spirits, Lady Caroline proposed acting a proverb, but it ended in acting a French word, orage. She, Lady Cork, and Miss White went out of the room and came back digging with poker and tongs. They dug for or (gold), they acted a passion for rage, and then they acted a storm for the whole word, orage. Still, the old general did not come, and Lady Caroline disappeared, but presently Mrs. Wellesley Pole and her daughter arrived, bringing with them a beautiful Prince—Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg (afterwards married to the Princess Charlotte), but saying that she feared Blucher would not come. “However,” continues Mrs. Opie, “we now heard a distant, then a near hurrah, the hurrahs increased, and we all jumped up saying, ‘There’s Blucher at last!’ The door opened, the servant calling out, ‘General Blucher!’ on which in strutted Lady Caroline Lamb (at left) in a cocked hat and great coat.”

Lady Cork’s house in New Burlington Street was most tastefully fitted for the reception of her illustrious guests: every part of it abounded in pretty things—objets, as they are sometimes called, which her visitors were strictly forbidden to touch. Beyond her magnificent drawing-rooms appeared a boudoir, and beyond it a long rustic room, with a moss-covered floor, with plants and statues; while the lower part of the house consisted of a handsome dining-room and library, which looked upon a small ornamented garden, where a fountain played; beyond these were a couple of rooms fitted up like conservatories, in which she received her guests before dinner.

Lady Cork was fond of showering expensive presents on those she liked. Mrs. Opie says, “Lady Cork has given me a most beautiful trimming for the bottom of a dress, which I am to wear on the 4th. It is really handsome, a wreath of white satin flowers worked upon net.” In addition, she could be generous to her friends in other ways. ” In 1780, the year of a general election, Sheridan’s (right) object was to get into Parliament if possible, and he was going to make a trial at Wootton-Bassett. The night before he set out, being at Devonshire House and everybody talking about the general election, Lady Cork asked Sheridan about his plans, which led to her saying that she had often heard her brother Monckton say he thought an opposition man might come in for Stafford, and that if, in the event of Sheridan failing at Wootton, he liked to try his chance at Stafford, she would give him a letter of introduction to her brother. This was immediately done. Sheridan went to Wootton-Bassett, where he had not a chance. Then he went to Stafford, produced Lady Cork’s letter, offered himself as a candidate, and was elected. For Stafford he was member till 1806 — six-and-twenty years.

Lady Cork was a woman of society to the end of her days; she either gave a dinner-party, a rout, or went out every night of her life. Lady Cork would borrow a friend’s carriage without asking her for it, and then innocently suggest that, as the high steps did not suit her short legs, her friend might have them altered for her future use. And not only for short distances or periods would she thus confiscate a carriage, but for the whole day and a long round of visits, leaving the owners to walk home or do the best they could. At home, the old lady, wrote Lady Chatterton, “gave very pleasant parties at her own house, too, and had a peculiar talent for adapting the furniture and everything in the room to promote real sociability and dispel shyness. Many of the chairs were fastened to the floor to prevent people pushing them into formal circles, or congregating in a crowd, or standing about uncomfortably.”

Of this charitable personage, Lady Clementina Davies writes: “Lady Cork was a most remarkable person, very little, and at the time I now mention nearly ninety years old. She used to dress entirely in white, and always wore a white crape cottage bonnet, and a white satin shawl, trimmed with the finest point lace. She was never seen with a cap ; and although so old, her complexion, which was really white and pink, not put on, but her own natural color, was most beautiful. At dinner she never drank anything but barley-water. She had often been at the court of France during the reign of Marie Antoinette, and had frequently met my father there. She said she had never forgotten what the old Princesse de Joinville told her, that la proprele was the beauty of old age, and therefore always wore white. She used to give great routs; and as people met everybody there, her rooms were always well filled. On one occasion, when we went to a large dinner-party at her house, she said to my husband, ‘Don’t be jealous, I have invited a very old friend of your wife; and when I told him I should invite her, he was perfectly delighted at the prospect of meeting her again after so many years. Now,’ she said, turning to me, ‘do you know who it is?’ And to my husband she added, ‘ He was a great admirer of hers when very young.’ I was trying to guess who it could be, when dinner was announced, and Lady Cork seemed very much annoyed and surprised that some person she expected had not come. We all sat down to dinner, and in a short time a note was brought to her. After reading it, she laughed, and sent it round to me. It was as follows : ‘ My dear Lady Cork, — I cannot express my regret that.it is quite out of my power to dine with you. And you will pity me when you hear that I am in bed. A blackguard creditor has had everything I possess taken from me. The only thing he has left me is a cast of one of Vestris’s legs. I must remain in bed till my lawyer comes, as I have not a coat to put on. This is the reason, dear Lady Cork, I cannot dine with you.’ We laughed very much, and as everybody wished to know the joke, Lady Cork told them, and the explanation of the cause of Lord Fife’s failure to keep his appointment made the dinner much more lively than if he had come.”

Lady Cork wrote, or rather had written for her—as she became nearly blind —a charming little note to John Wilson Croker, asking him to dine with her on her ninetieth birthday. His only idea was to convict her of an error as to her age. “I found,” he said, “by the register of St. James’s parish, that she had under-stated her age by one year !”

She lived till May 30, 1840, having finished her ninety-third year. What a wonderful succession of wits, philosophers, beauties, poets, dramatists, novelists, had passed through her salons! In London society she certainly filled up a gap: at that time, stiffness and monotony reigned supreme—Lady Cork broke down the barriers. From her, all who were distinguished in any way found a welcome; she even received the Countess Guiccioli (abovve, Byron’s mistress and friend to Lady Blessington and Count D’Orsay), and made a lioness of her for a season. Even a savage in his war paint would not have been excluded, and by degrees the dull decorum which had marked many of the London drawing-rooms became broken down.

There was always something to see at Lady Cork’s, and her delightful bonhomie and joyousness gave a charm even to her Blue parties. She formed a link between two centuries, and London society owes her a debt of gratitude. Lady Cork was interred in the family vault of the Monckton family, at Brewood, in Staffordshire.

Originally published in 2010