Victoria here again, effusing about my visit to New Haven CT to experience in person the delights of Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance. At left is a self-portrait painted in 1787-88, the earliest work in the exhibition, I believe. It certainly shows great technical ability and promise. Lawrence was only about eighteen at the time. According to the catalogue essay by Lucy Peltz (Curator of 18th-century Paintings, National Gallery, London), he wrote home at the time from London: “Excepting Sir Joshua, for the painting of a Head, I would risk my reputation with any painter in London.” Amazing confidence for one so young. But he had been a prodigy since early youth, encouraged by his innkeeper father to sketch customers to the extent that young Tom was the family’s primary support. He had occasional stretches of formal education at the Royal Academy, but his career outstripped almost all advice and pedagogy. By 1789, he was painting a portrait of the Queen at Windsor.

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818) married King George III in 1761 when she was seventeen years old. She bore him fifteen children. When she sat for Lawrence, rather unwillingly it seems, she was about 45 years old and disturbed by the King’s recent bouts of peculiar illness, both mental and physical. The events of 1789 in France did not help. Queen Charlotte had been painted by many artists, including Allan Ramsay,

Benjamin West, Johann Zoffany, Reynolds, and Gainsborough. Neither the Queen nor the King liked the Lawrence and never paid him. But it was highly praised at the 1790 Royal Academy exhibition and is now in the collection of the National Gallery, London.

Arthur Atherley (1771-1844) was painted in 1792 when he was about age twenty. Exhibited simply titled “Portrait of an Etonian,” the painting was said by one reviewer to be comparable to Sir Joshua (Reynolds), certainly high praise for Lawrence, the relative newcomer to the London art scene.

Mary Hamilton, Later Mary Denham, d. 1837

graphic and red and black chalk, executed in 1789

Mrs. Hamilton read to Lawrence and her husband, artist William Hamilton, while they drew antique statues in the evening. This drawing was probably a gift to the couple, though Lawrence sent it to the RA for exhibition in 1789. As Lawrence’s star rose, however, Hamilton’s career did not flourish and the two men grew apart.

William Lock, the Younger (1767-1847), drawn in black chalk on canvas, sometime between 1795 and 1800.

One of the strengths of this exhibition is the excellent selection of drawings by Lawrence, which are far less familiar then his dazzling oil portraits, but equally pleasing to the visitor.

Lock was part of the “charmed circle” of families that Lawrence became part of, including the Angersteins and Locks. He drew and painted many members of the families and particularly their children.

William Lock’s sister Amelia married John Angerstein in 1799.

This portrait of John Julius Angerstein (1796-1823) was painted in 1790. Angerstein was a wealthy insurance broker in the City of London and one of Lawrence’s earliest supporter, as patron, friend and banker. He was important to the development of Lloyd’s of London, and was a prominent art collector. He was born in Russia, and it has been rumored that he was the illegitimate son of Catherine the Great, but it is more likely that he was of much more modest birth. Nevertheless, he acquired a considerable fortune. Lawrence advised Angerstein on some of his old master purchases. After his death, the collection was purchased by the government to be part of the new National Gallery which now sits above Trafalgar Square.

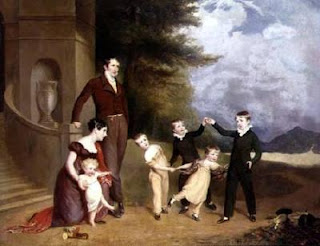

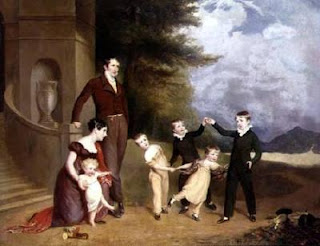

These Children of John Angerstein, painted in

1807, were the grandchildren of John Julius Angerstein, above. The choice of pose is unusual in that wealthy children of privileged families are rarely portrayed with shovel and broom. The catalogue essay speculates that the elder Angerstein’s philanthropic interest in children would promote, “the hoped-for future for children…the right to play outdoors and enjoy autonomy, and to influence one another through action and word. If a child sweeps as young John Julius Angerstein does, he should do so for enjoyment. In this way the children embody the promise of philanthropy for future generations.”

Countess Therese Czernin (1798-1896), drawn in 1819, was the daughter of an Austrian general. Apparently it remained in the family of the countess and was not known until it was sent to an auction in 1985, where it was revealed as the work of Lawrence. It is now owned by a private collection. It makes one wonder what other treasures might be lurking in some old castle attic. Another work by Lawrence? A letter from Jane Austen? A lover’s eye ring? If you find anything in your castle, please send word.

Countess Therese Czernin (1798-1896), drawn in 1819, was the daughter of an Austrian general. Apparently it remained in the family of the countess and was not known until it was sent to an auction in 1985, where it was revealed as the work of Lawrence. It is now owned by a private collection. It makes one wonder what other treasures might be lurking in some old castle attic. Another work by Lawrence? A letter from Jane Austen? A lover’s eye ring? If you find anything in your castle, please send word.

Several years ago, I stayed at the National Trust Hotel that is part of Ickworth, an estate in Suffolk, built by the Earl Bishop, Frederick Hervey (1730-1803), 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry (see our post of 3/9/11). He built his remarkable house in the last decades of the 18th century. One of his daughters was Lady Elizabeth Hervey (1757-1824), who married John Foster in 1776. After having two sons with Foster, Bess left him and in 1782 became the close friend and confidante of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. She enjoyed a rather warm relationship with William Cavendish (1748-1811), 5th Duke of Devonshire, as well and bore the duke two children who were raised with the three legitimate Cavendish children. Speculating on the precise nature of this menage a trois tickles our imagination. After Georgiana died in 1806, Lady Elizabeth became the 5th duke’s second wife in 1809. He did not survive long, dying in 1811, but she lived on as the Duchess of Devonshire until 1824. If she indeed resembled this portrait drawn by Lawrence when she was age 63 or so, one might understand what kind of charisma the lady had.

Occupying an interesting point between chalk drawings and a finished painting is this unfinished portrait of Emilia, Lady Cahir, later Countess of Glengall (1776-1836) done in 1804-05. There are three heads here, though it is difficult to see the one on the left. It is visible in the exhibition if you look closely. You might be able to make out the lips and the nose of the left-most head just below and to the left of the center head’s chin.

The work was perhaps done at a house party at Bentley Priory where Emilia and Thomas Lawrence both played roles in theatricals. Bentley Priory belonged to the Marquess of Abercorn and was the scene of many country house theatricals.

Charles William (Vane-)Stewart, later 3rd Marquess of Londonderry (1778-1854) was painted in 1812. The catalogue says it is “celebrated as one of the ultimate icons of British military portraiture.”

As Undersecretary for War and one of Wellington’s Adjutant-Generals, Stewart cuts a glamorous and colorful figure. His uniform is of a cavalry officer, a dashing hussar, with the details and medals highlighted. The portrait also represents a turning point for Lawrence, bringing him an introduction to the Prince Regent and eventual commissions for the Waterloo Chamber portraits (detailed in my next post on the Yale exhibition).

George James Welbore Agar-Ellis, later 1st Lord Dover (1797-1833), painted a decade later in 1823-24, shows Lawrence extending his bravura palette of colors into the world of the civilian male. He was particularly fond of Agar-Ellis who proposed that Parliament purchase the collection of the Late J.J. Angerstein (see above) for the nucleus of a national collection.

To complete this trio of handsome Regency heroes, the portrait at left, again over life size, seems to sum up everything about an aristocrat in his element: Lord Granville Leveson-Gower (1773-1846), later 1st Earl Granville, whose expression, almost a smirk, is absolutely perfect. He was painted in 1804-06 when he was serving as British Ambassador to Russia. Later he was ambassador France.

A younger son of the 1st Marquess of Stafford, he married Lady Harriet Elizabeth Cavendish (1785-1862), known as Harry-O, daughter of the 5th Duke of Devonshire and his wife, Georgiana, in 1809. They had five children and raised the two by-blows Granville fathered with his mistress, Harry-O’s aunt, Lady Harriet Bessborough. He was raised to the peerage as a Viscount in 1815 and to the title of Earl Granville in 1833.

This painting of Lord Granville Leveson-Gower dates from 1804-1809 and is part of the YCBA’s Paul Mellon Collection

Though it might not sound like an auspicious beginning for a marriage, with Granville’s several affairs kn

own to Harry-O, apparently it grew into a strong relationship, as both partners also grew in religious fervor — along with many of the formerly-loose members of Regency society as the years passed into Victorian sobriety and admiration for moral rectitude. At right, a painting of the happy Granville family by Thomas Phillips. Definitely NOT a Lawrence and not in the exhibition.

Rosamund Hester Elizabeth Pennell Croker, later Lady Barrow (1809-1906) was painted by Lawrence in 1826. When exhibited at the RA in 1827, it was highly praised and often surround by admiring patrons.

In the catalogue essay, Cassandra Albinson writes, “Lawrence felt one could judge artists’ skill by how they executed white satin, as in the dress depicted here.” I would say this one is very skillful!

Notice that she lived a very long life, reaching the age of 96 or 97.

Lady Selina Meade, later Countess of Clam-Martinics

(?1797-1872 ) was painted in Vienna in 1819 and exhibited at the RA the next year. Observers called attention to the highlights of her pearl earrings and gold headband as perfect compliments to her beauty. Note also the excellence of the white satin. The catalogue contends she had been courted by Lord Granville Leveson-Gower but in 1821 she married an Austrian, Karl Graf von Clam-Martinics.

Julia Beatrice Peel (1821-93) was painted in 1826-28 when she was about 6 years old. Another adorable child, like we saw in my earlier post on this exhibition. One of Lawrence’s true gifts was his ability to portray the beauty and innocence of children. Julia Peel was the daughter of Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) who was Home Secretary at the time of the portrait. Later he served as Prime Minister 1834-35 and again 1841-45. He founded the London police force; they are still called Bobbies, after him. Julia married George Augustus Frederick Child Villiers, who became the 6th Earl of Jersey, so she was another Lady Jersey. This portrait, like that of Leveson-Gower, is shown only at Yale.

William Wilberforce (1759-1833) is the man who campaigned for more than twenty years to end the slave trade, which was accomplished in 1807. In 2006, there was an excellent movie about his life, titled Amazing Grace. I recommend it; though it has a few historical inaccuracies, the gist is correct. Making up for any deficiencies in the facts are the excellent performances by a fine cast: Ioan Gruffudd as Wilberforce, Romola Garai as Barbara Spooner, Benedict Cumberbatch as William Pitt the Younger, Albert Finney as John Newton (who wrote the famous hymn), Michael Gambon as Charles James Fox (who actually died before the bill passed), and Rufus Sewell as Thomas Clarkson.

Here is a final self portrait by Lawrence, painted in 1825, five years before his death. Like the Wilberforce and many other of his canvasses, it was unfinished. Lawrence left a huge number of semi-completed pictures in his Russell Square studio some of which had already been paid for. He also left numerous debts.

I would never presume to be able to divide the pictures into the two categories of the Power and the Brillliance, but I almost have done so in this post — the Brilliance. And in my third post, I will concentrate on the Power. Stay tuned. And just to remind you of how lucky I was to have a fellow writer as a companion, here is a repeat of us in front of the exhibition, Diane Gaston on the right.

The interior of the YCBA is very comfortable and welcoming. I like a museum where there are lots of seats where one can sit and look at the pictures — and this gallery has the added advantage of windows to the outside. The picture in the center is by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), a work with the kind of realistic detail he later eschewed. It is titled Dordrecht, the Dort Packet-boat from Rotterdam Becalmed painted in 1818. I love almost everything by Turner but this particularly engages me.

The interior of the YCBA is very comfortable and welcoming. I like a museum where there are lots of seats where one can sit and look at the pictures — and this gallery has the added advantage of windows to the outside. The picture in the center is by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), a work with the kind of realistic detail he later eschewed. It is titled Dordrecht, the Dort Packet-boat from Rotterdam Becalmed painted in 1818. I love almost everything by Turner but this particularly engages me. Here is another view of the galleries, photos attributed to Richard Caspole. Although I wouldn’t mind being the only patron for a few hours, I must say the place has never been empty when I visited. The building was designed by was Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974), once a professor of architecture at Yale, and a leading American mid-century architect. The YCBA is immediately across the street from the Yale Art Gallery, also designed by Kahn, now undergoing renovations.

Here is another view of the galleries, photos attributed to Richard Caspole. Although I wouldn’t mind being the only patron for a few hours, I must say the place has never been empty when I visited. The building was designed by was Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974), once a professor of architecture at Yale, and a leading American mid-century architect. The YCBA is immediately across the street from the Yale Art Gallery, also designed by Kahn, now undergoing renovations.