On a recent visit to London, Victoria Hinshaw and I went to see the Style & Society Exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. Over the years, Victoria and I have been fortunate enough to see many such shows at the Queen’s Gallery and they never disappoint.

From the Royal Collection Trust website:

“Discover what fashion can tell us about life in 18th-century Britain, a revolutionary period of trade, travel and technology which fuelled fashion trends across all levels of society. Delve into the Georgians’ style story and get up close to magnificent paintings, prints and drawings by artists including Gainsborough, Zoffany and Hogarth, as well as luxurious textiles, sparkling jewellery, and a range of accessories from snuff boxes to swords.

“The exhibition reveals how the Georgians ushered in many of the cultural trends we know today, including the first stylists and influencers, the birth of a specialised fashion press and the development of shopping as a leisure activity.”

Stitched Stays, c 1780s (Fashion Museum, Bath) – Made of cotton, linen and baleen, these stays were worn over a shift. The form is achieved by inserting narrow strips of baleen into hand stitched channels between layers of fabric. The workmanship on this particular example is of the highest quality.

George III when Prince of Wales, 1759 by Sir Joshua Reynolds – The future king is dressed in a richly embroidered velvet suit. The ceremonial red velvet robe is lined with ermine, with the black tails of the stoat sewn into a pattern of black spots known as powderings. In private life, George III preferred much plainer dress, due to both his nature and his frugality.

Sleeve ruffles of Alencon needle lace, French 1755-65. This type of needle lace was made using a needle and thread, rather than a bobbin.

On the left, Princess Caroline (third daughter of George II) wears a black silk hooded mantle. Miniature by Christian Friedrich Zincke. On the right, Princess Amelia (youngest daughter of George III) wears a blue velvet Spencer. Miniature by Andrew Robertson 1811. These miniatures are singular in that they depict the Princesses in practical dress, rather than the court dress more typical in royal portraits.

Above, a Bill from Andreas Meyer 15 April – 4 July 1801 for footwear purchased by the Prince of Wales, including five pairs of Hussar boots with high heels, each costing the equivilant of £250 in today’s money.

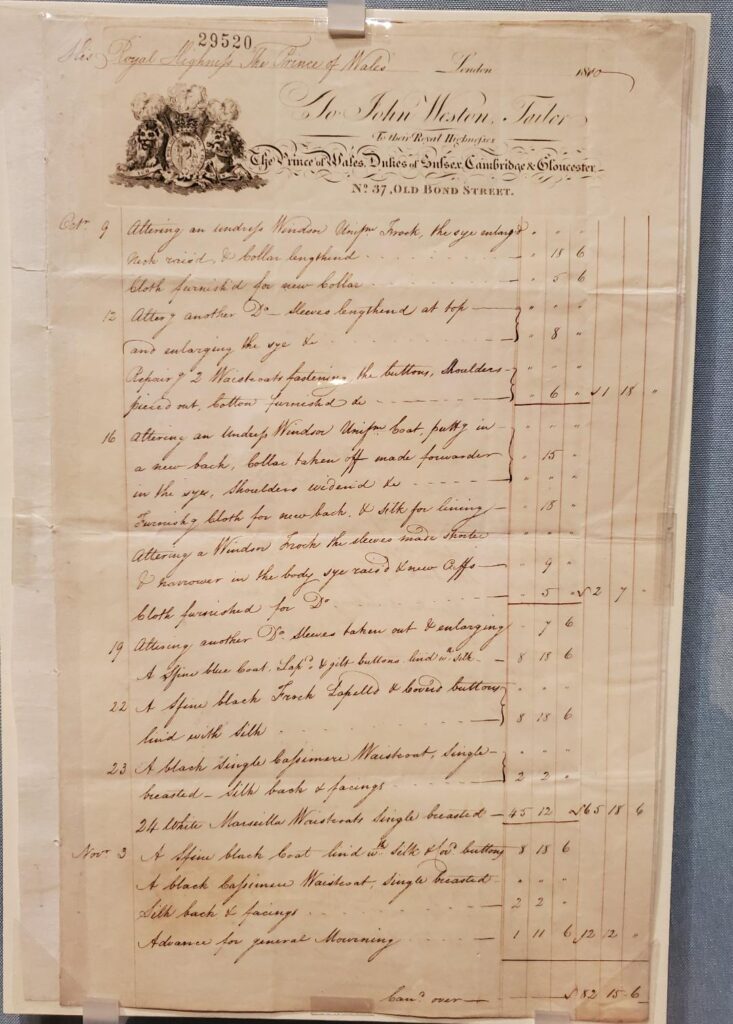

Below, a Bill from John Weston 9 October – 3 November 1810 for clothing including 24 White Marseille Waistcoats and a superfine black frock coat lined in silk.

Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, later Second Marquess of Londonderry by Sir Thomas Lawrence. Castlereagh’s clothing demonstrates that by the early 19th century, gentlemen’s dress incorporated elements of smart country clothing for everyday dress. Simple lines that relied upon a tailor’s skill and quality material in more sombre tones replaced Georgian ostentation.

Baby shoes worn by Princess Charlotte 1796-8, made of soft twill-woven cotton with cream silk satin ribbon rosettes, fastened with string ties.

By Nicolas Noël Boutet 1814, a pair of double-barrelled flintlock pistols, ramrods, priming flask, screwdriver, bullet mould and lead shot. An example of the pieces produced in the Versailles factory. Gifted to George IV by Louis XVIII, they include intricate ornamentation. Pistols almost never appear in portraits from this period, while the tradition of painting gentlemen with swords was prevelant in the Georgian era.

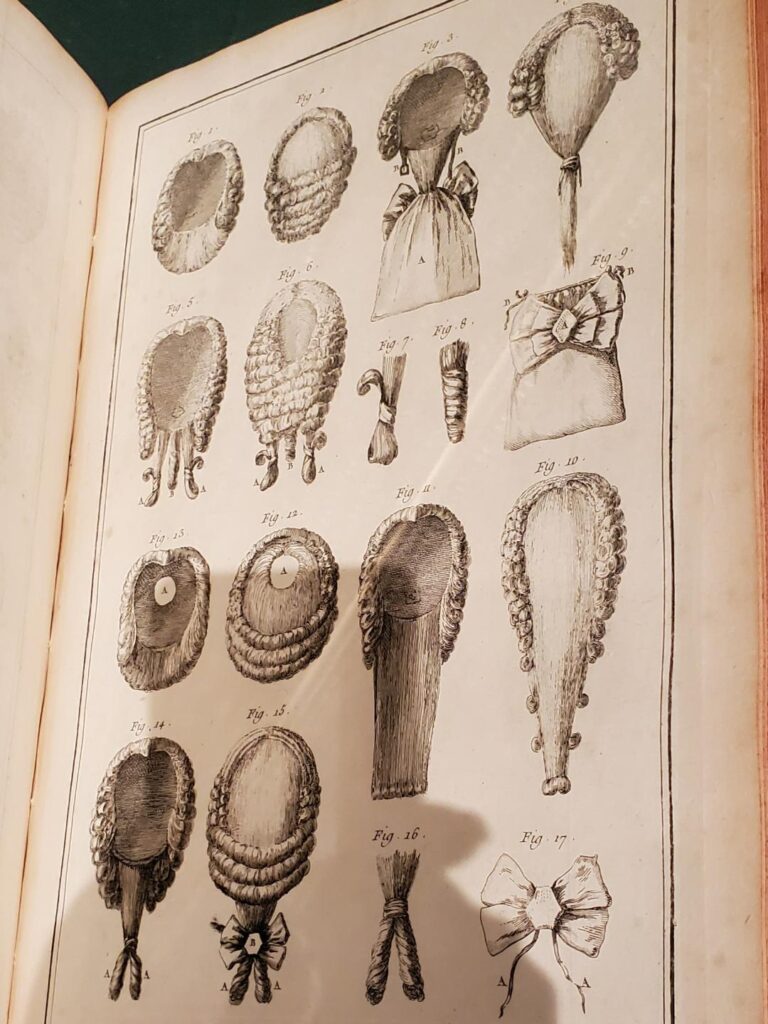

Above, Denis Diderot’s Encylopédie 1771. Diderot was a perruquier and barbier and his Encylopédie includes the most complete description of the wigmaking process of its time. Below, an example of an English wig and wig bag.

This beautiful dress, on loan from the Fashion Museum Bath, is recorded as having been worn at court in the 1760s. The Bath mantua is made of cream silk and the surface of both the gown and petticoat are covered with embroidery of the very highest quality.

George IV when Prince of Wales 1791 by John Russell. The prince wears the civilian uniform of the Royal Society of Kentish Bowmen. On the stone plinth is the black round hat with feather, “without which no member was allowed to shoot.”

Laetitia, Lady Lade 1793 by George Stubbs. Lady Lade’s riding habit would have been made by a male tailor, unlike gowns which were made by female dressmakers. During the 1790’s muted dark shades were most fashionable, following the trend in men’s fashion.

Mary Delaney, née Granville 1782 by John Opie. Mrs. Delaney is portrayed in her widow’s weeds. The plain black dress is worn with a white cap with “falls” on either side of her face. Mrs. Delaney was a good friend of Queen Charlotte’s and, like members of royalty, chose to wear mourning attire far beyond the time limits imposed by conventions of the day.

Victoria, Duchess of Kent by George Dawe 1818. Unusually, the Duchess (mother to Queen Victoria) wears mourning in this portrait. Her set of diamond jewellery suggests that she is in the second stage of mourning for her niece, Princess Charlotte, who died in childbirth the year before.

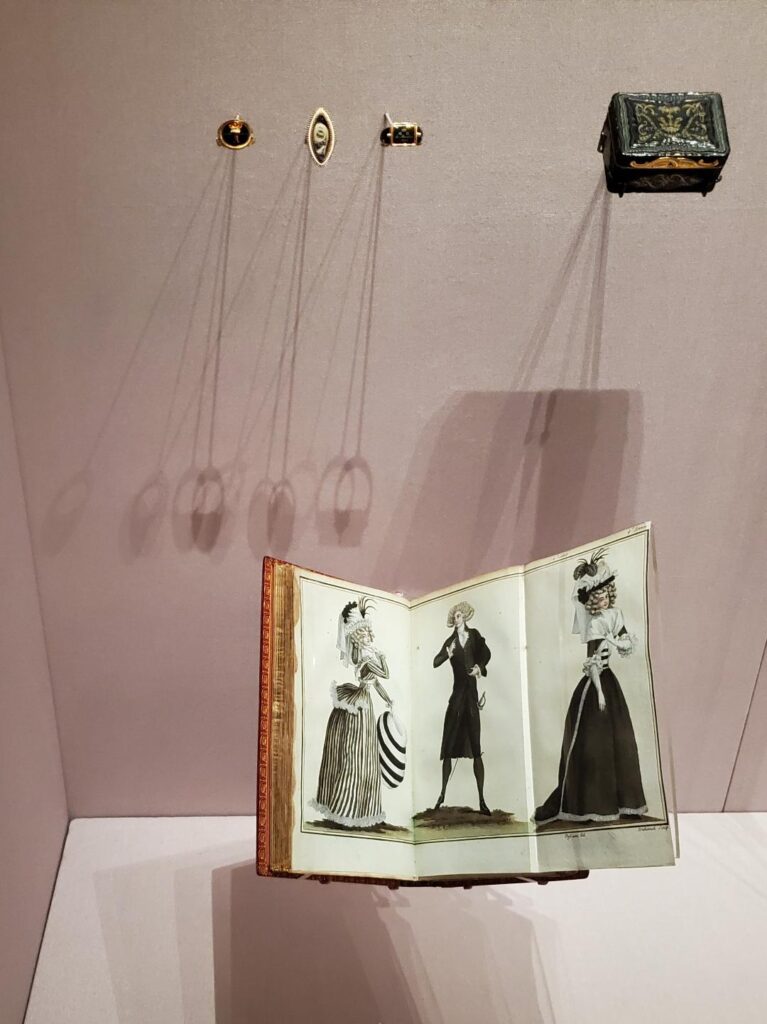

A man and two women in second stage grand deuil (mourning), from Magasin des Modes Nouvelles, Françaises et Anglaises, 11 March 1789. The illustration depicts the trend for stripes, muffs and double watch chains during second mourning. The gentleman carries a blue, half hilted mourning sword.

This sword display demonstrates the progress from first mourning, where all accessories were required to be matt black and made from black steel, to half mourning when swords often incorporated blued steel blades and hilts inset with stones, glass or beads.

The magnificent dress was worn by Princess Charlotte on her marriage to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld on 2 May 1816. Charlotte’s wedding dress was a masterpiece of Georgian-era fashion and remains one of the most iconic bridal gowns in history. It is the only royal wedding dress that survives from the Georgian period.