By Victoria Hinshaw

I love the word – and the concept of – Serendipity. The word was invented by one of the 18th century’s most interesting characters, Horace Walpole (1717-97), whose life neatly spanned the century and, to my mind, rather defined the times.

Serendipity means discovering connections between thoughts or objects by happy accident. I first learned the word when I had a most pleasant meal on E. 60th Street in New York City at a charming restaurant named Serendipity. It was a serendipitous event! The discovery of a new concept while in the act of enjoying a new place (this was a very long time ago).

Recently, while working on a piece for this blog (see posts of March 29 and 31) on William Petty-FitzMaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (1737 – 1805), who was The Earl of Shelburne and Prime Minister 1782-1783, I learned that Walpole, himself an opinionated and eccentric character, did not like Shelburne, also famously opinionated and eccentric. How serendipitous, I thought, for I was also planning to do a piece on Walpole and the upcoming exhibitions of his treasures at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Which reminded me of the restaurant in New York; when I Googled it, I happily found it still prospering. Then I read that Walpole had coined the word Serendipity.

Amazing.

All of which is a long and involved introduction to my little essay on Horace Walpole, architect, author, collector, raconteur, bon vivant, and writer of 48 printed volumes of correspondence.

Horace was a younger son of Sir Robert Walpole, first Earl of Orford, and England’s first Prime Minister during the reign of the first two Georges. Horace received an ideal gentleman’s education at Eton and Cambridge followed by a Grand Tour. He had wide ranging interests and made many friends, devoting himself to arts and culture. Though he served as a member of the House of Commons, he had an independent income which enabled him to pursue his eclectic interests by collecting and carefully developing his tastes. Widely considered a superb connoisseur, he and his friends spent years converting his villa in Twickenham into a neo-Gothic structure.

Strawberry Hill

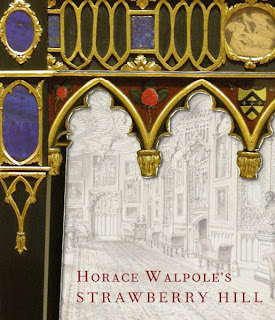

My immediate interest is in the

exhibition which, according to reports, recreates the ambience of the actual house: Horace Walpole and Strawberry Hill. Kristine has already seen the entire show when it was at the Yale Center for British Art, in New Haven, Connecticut. Her report: “I loved it. Many dark gothic-looking pieces he’d collected.” I can’t wait to see it in June in London.

In her review of the V and A Exhibition, Amanda Vickery quotes Michael Snodin, curator of the exhibition. He writes: Walpole “as a lively and incisive commentator shaped the way we see 18th-century politics and society. As the most important collector of his time he created a form of thematised historical display which prefigured modern museums. And Strawberry Hill was the most influential building of the early Gothic revival.” Her

full review here.

The house itself, along with its collections, was developed over a period of years, adding or redoing a room from time to time, between 1747 and 1790. Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill is published by Yale University Press in association with the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University; the Yale Center for British Art; and the V and A. The catalogue is edited by the exhibition curators, Michael Snodin of the V and A and Cynthia Roman of the Lewis Walpole Library.

It was at Strawberry Hill that Horace Walpole wrote The Castle of Otranto, published in 1764, the prototype for the Gothick novel boom that consumed popular literature for several succeeding decades.

Here is another aside: Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey is a parody of Gothick novels that always featured an innocent young lady at peril in an old castle or ruined religious structure, fearing at every moment the mysterious rattle of chains, the gloomy wailing of the winds and the sinister dark males that threaten A Fate Worse Than Death. Rather reminds me of the current crazes for vampires, werewolves and zombies.

Walpole, or his housekeeper for the less exalted tourists, often gave tours to visitors. He created and printed a guidebook to the house and its collections. After he died in 1797, the house was left to his friend and relative Lady Anne Seymour Damer, a renowned scupltor in her own right. She died without issue and their mutual relatives, the Waldegraves, took over. In 1842, the contents of the house were auctioned. The exhibition brings together for the first time since then almost 300 items from Walpole’s collections and furnishings. The

Strawberry Hill house is being renovated and will reopen soon.

One of the highlights is a suit of gilded parade armour. Walpole

believed it belonged to King Francis I of France but the V and A curators date it about 1600.

Horace Walpole’s intimate personal life has fascinated fellow dilettantes as well as scholars and literary analysts. He never married and was known for effeminate behavior. He numbered many man and also many women among his closest and most intimate friends. But no one has proven anything; perhaps the best answer is that he was asexual, turning his energies to his collections and other artistic interests.

Among Horace Walpole’s greatest achievements are the many insights his letters and other writings give into the society politics and culture of 18th Century Britain.

He was witty, erudite and voluble. Just reading a few letters makes one long for just an hour of his time to enjoy the conversation in person rather than on the page. Some have called him pretentious, effete, arrogant and peculiar. Perhaps those qualities only added to his charm.

Right, Strawberry Hill interior

To conclude, where did Horace Walpole come up with that word SERENDIPITY? He found it in a Persian story, once the name for Sri Lanka. Here is a quotation from a letter he wrote in 1754 to Horace Mann, an English friend who lived in Florence:

“It was once when I read a silly fairy tale, called The Three Princes of Serendip: as their highnesses traveled, they were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of: for instance, one of them discovered that a camel blind of the right eye had traveled the same road lately, because the grass was eaten only on the left side, where it was worse than on the right—now do you understand serendipity? One of the most remarkable instances of this accidental sagacity (for you must observe that no discovery of a thing you are looking for, comes under this description) was of my Lord Shaftsbury, who happening to dine at Lord Chancellor Clarendon’s, found out the marriage of the Duke of York and Mrs. Hyde, by the respect with which her mother treated her at table.”

If you are fortunate enough to be in London in the next few months (6 March-4 July, 2010), I hope you will join the V and A and me in celebrating the fascinating, serendipitous Horace Walpole.