In a perfect world, thirty-four year old, London born actor Benedict Cumberbatch would be lauded simply for using his real name professionally – he is the son of actors Timothy Carlton (birth name Timothy Carlton Cumberbatch) and Wanda Ventham. As this has not yet happened, it’s a good thing that Cumberbatch has instead been receiving accolades for his acting talents.

Cumberbatch was educated first at Brambletye School in West Sussex, and then at the prestigious Harrow School in northwest London, where he began performing as an actor. After graduation, he took a gap year to teach English in a Tibetan monastery. He then attended the University of Manchester, where he studied drama. At the university, he met his longtime girlfriend, actress Olivia Poulet. After graduating, Cumberbatch trained further in acting at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

Cumberbatch told an interviewer that his parents had “worked incredibly hard to give me a very privileged education, so I could do anything but be as stupid as them and become an actor. Unfortunately, I didn’t pay any notice, like a lot of children, to my parents’ wise words. For awhile, I did toy with being a criminal barrister. I thought that would be quite fun. Then an awful lot of people dissuaded me from that path, basically saying, `It’s unpredictable. You don’t know where your next job is coming from. You have to travel up and down the country to God-forsaken holes of depravity, and it’s very lowly, incredibly hard work.’ I thought, “This sounds a bit like acting, so I’ll stick with that.”

Cumberbatch began his career on the stage, appearing in, amongst other things, Hedda Gabler at the Almeida Theatre in 2005. His performance as Tesman brought him an Olivier Award nomination for Best Performance in a Supporting Role. A year earlier, Cumberbatch had garnered a BAFTA TV Award nomination for Best Actor for his role as Stephen Hawking in Hawking.

That same year, whilst filimig To The Ends of the Earth, Cumberbatch, along with co-stars Denise Black and Theo Landey, were carjacked in South Africa when they were stopped at the side of the road with a flat tyre. Six men appeared, held the trio up against the car and tied their hands with their own shoelaces. During the car-jacking, which lasted two and a half hours, Cumberbatch was held in the boot of the car.

In 2006, Cumberbatch played William Pitt in Amazing Grace, the film is the story of William Wilberforce’s intense and lengthy political fight in the late 18th century to eliminate slave trade in the British Empire. The role earned Cumberbatch a nomination for the London Film Critics Circle British Breakthrough Acting Award.

Cumberbatch subsequently appeared in major roles in

Atonement (2007) and

The Other Boleyn Girl (2008). In 2009, he appeared in Darwin bio-pic

Creation, as Darwin’s friend Joseph Hooker.

Speaking to the Guardian about his roles, Cumberbatch said that people think “I just play neurotic, fey people who would have died with a cold compress to their head. But I do work on the variety. I do try.”

And he’s succeeded – he is scheduled to appear in The Whistleblower (2010) and Steven Spielberg’s War Horse (2011). Cumberbatch will also play Peter Guillam in the 2012 adaptation of the John le Carré novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, directed by Tomas Alfredson, also starring Gary Oldman, Colin Firth and Tom Hardy. Begining in February, Cumberbatch returns to the stage in Oscar-winning director Danny Boyle’s version of Frankenstein, in which Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller will swap the roles of monster and doctor on alternate nights.

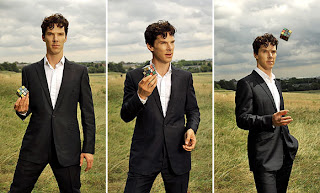

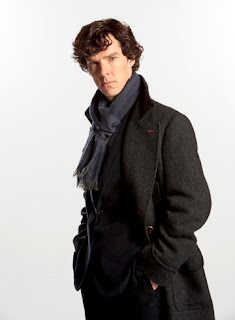

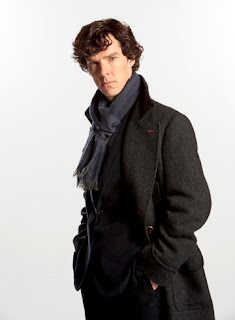

For now, we’ll watch Cumberbatch in PBS’ Masterpiece Mystery! as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s classic detective Sherlock Holmes. Speaking about the role, Cumberbatch said: “It is the most-played literary, fictional character. It’s in the Guinness Book of World Records for it. I follow in the footsteps of about 230-odd people, in many different languages, at different ages and different times. For any actor to play an iconic character, there’s a huge pressure that’s associated with delivering something that everyone knows culturally, especially in our country. So, it was quite nerve-wracking, but there is an element of a blank canvas because of this brilliant re-invention and re-invigoration of him being a 21st century hero. While it maintains the integrity of Conan Doyle’s original, much to the enjoyment of die-hard fans of the books, hopefully it will turn new people onto the books, which will be a good thing.”

So what’s next? Cumberbatch and his girlfriend, actress Olivia Poulet, would like to have children one day. And Cumberbatch would eventually like to find the time to try his hand at writing. In the meantime, his legions of fans are content to watch, instead of read, him. Check out the ultimate Benedict Cumberbatch

fan site here – btw, his female fans have tagged themselves “Cumberbitches.”

Starting with a brief history of monasticism in England and the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, we then focussed on what happend to the former abbey buildings and why they were considered so spooky — and/or picturesque.

Starting with a brief history of monasticism in England and the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, we then focussed on what happend to the former abbey buildings and why they were considered so spooky — and/or picturesque.

Ruined abbeys, castles and wild landscapes appealed to the writers of gothic fiction, so popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Mrs. Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho is the novel Jane Austen parodied in Northanger Abbey. Terrible secrets are hidden in the ruins, dangerous forces threaten the innocent heroine, but all comes to a happy ending when she is rescued by a worthy hero. Such stories were all the rage in JA’s day and many were set among the imagined clanking chains, ghostly moans and dark passages of ruined abbeys.

Ruined abbeys, castles and wild landscapes appealed to the writers of gothic fiction, so popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Mrs. Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho is the novel Jane Austen parodied in Northanger Abbey. Terrible secrets are hidden in the ruins, dangerous forces threaten the innocent heroine, but all comes to a happy ending when she is rescued by a worthy hero. Such stories were all the rage in JA’s day and many were set among the imagined clanking chains, ghostly moans and dark passages of ruined abbeys. Stoneleigh Abbey, an estate inherited by Jane Austen’s relatives, was built on the property of an ancient abbey, and landscaped in the early 19th century by Humphrey Repton. Jane Austen visited here and mentions Repton’s schemes for landscapes in her novels.

Stoneleigh Abbey, an estate inherited by Jane Austen’s relatives, was built on the property of an ancient abbey, and landscaped in the early 19th century by Humphrey Repton. Jane Austen visited here and mentions Repton’s schemes for landscapes in her novels. We know that Jane Austen visited Netley Abbey in Hampshire while she was living in Southampton. It was a popular venue for picnics and walks, as were so many of the abbey ruins spread over the entire British Isles. One of the most famous, below, is Tintern Abbey, maybe best known from the paintings of Turner.

We know that Jane Austen visited Netley Abbey in Hampshire while she was living in Southampton. It was a popular venue for picnics and walks, as were so many of the abbey ruins spread over the entire British Isles. One of the most famous, below, is Tintern Abbey, maybe best known from the paintings of Turner.