Inspired by Kristine’s London, posted on April 7, 2010, I decided to write about MY London.

I first visited as a college student and remember only Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, a few nameless pubs, and the Tower of London. My next visit was a few years later, shortly before Christmas. I loved the lights on Regent’s Street and my introduction to Liberty, a fabulous store to which I return almost every time I get to England. Once I finished my holiday shopping, I attended a performance of Handel’s The Messiah at St. Paul’s Cathedral in the presence of the Queen Mother. I actually got a glimpse of her as she entered. Needless to say it was a memorable experience.

An aside about Liberty of London. Have you seen the great stuff now in Target Stores from Liberty? They have a current ad campaign in lots of glossy mags such as Vogue and Vanity Fair.

Although I adore the great museums of London: the British Museum, the National Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and many more, I have a special affinity for the smaller museums where I can browse without rushing to be sure I don’t miss anything. One of these is Apsley House, the home of the first Duke of Wellington, but Kristine has already described it, so I will just say, “Me too.”

Among my faves is Sir John Soane’s Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Square. Soane (1753-1837) was a brilliant architect. His house was not only a residence but also his school at which he trained young architects. It sums up all that is generous and eccentric about the British character, at least to me, for he left it to the nation to be open free in perpetuity.

Typical of the convoluted sagas of many British families is the story behind the Wallace Collection, an outstanding art museum in Hertford House, Manchester Square. The entire tale is told on their website; it includes royal mistresses, stupendous fortunes, illegitimate sons, marriage to a floozie, and generous public bequests.

Another museum I enjoy visiting is the Geffrye Collection of period rooms. right.

I’ll mention two more small museums I like:

The Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, just across Lincoln’s Inn Fields from Sir John Soane’s. It was begun in 1799 and has some of the original collections, including John Hunter’s (1728-1793) on the development of bones as well as specimens collected by renowned botanist Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820).

And the Fan Museum in Greenwich. Not as famous as Greenwich’s other museums or the Observatory, but delightful all the same.

I often spend time pawing around in libraries and research centers, so I have to include The British Library, the National Archives, the Family Record Center, the Westminster Archives, the Colindale Newspaper Archives of the BL, and the Guildhall Library, all of which have helped my researching. This trip in June 2010 will mark my first trips to the VandA Art Library and the Hertfordshire Archives. Wish me luck!! I know there are lots of you out there who, like Kristine and me, love to pour over new sources of information wherever they are. Someday I want to obtain a membership in the London Library in St. James Square, the epitome of a research heaven.

As I have outlined before, I adore exploring houses, both modest and sumptuous. Among less pretentious are the Dickens House and the Carlyle House, where we see how the merely comfortable lived. But the big treasure houses are even more fun. Three of my favorites are out in the suburbs today, but they were once country retreats.

Anyone who loves the stories of Sally, Lady Jersey (see this blog’s post of April 2, 2010) should visit Osterley Park. There she (granddaughter of the banker Robert Child)and her husband entertained lavishly. The house is magnificent and well worth the trouble of getting there.

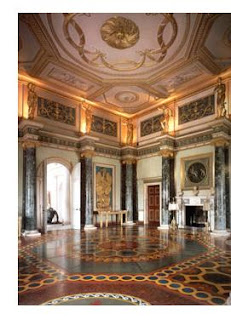

Ante Room, Syon

The same thing goes for Syon House, home of the Dukes of Northumberland, which has perfect Robert Adam décor. The circuit of rooms, from the starkly classical black and white of the entrance hall, through the brilliantly colored Ante-Room to the dining room, the Red Drawing Room and the Library, provides the ideal impression of a great country house.

Chiswick House

The third outlying property is Chiswick House, the Palladian model built by the 3rd Earl of Burlington in 1729. It became the property of his youngest daughter, Lady Charlotte Boyle, wife of the 4th Duke of Devonshire. During the time of the Fifth Duke and his Duchess Georgiana, it was a center of aristocratic social and political life. The house is a perfect jewel box surrounded by a lovely garden.

Now that I am sounding rather like a travelogue, I want to advise visitors to London to take advantage of the reasonably priced and never disappointing London Walks. I have never had a bad experience with any of their offerings, and I have taken many including Explorer Days Out. The only problem is that the crowds get large during the height of the tourist season. Just make sure that you are dealing with the original London Walks, not some rip-off outfit.

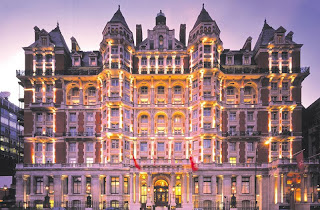

In the many times I’ve been to London, I’ve stayed in all sorts of places, from huge tourist hotels (dumps) to small BandBs to one memorable interlude at the Mandarin Oriental Hyde Park (guess which I liked best). I’ve rented apartments in several neighborhoods and a house in Chelsea. London is hard on the budget, but if you look carefully, there are reasonable accommodations and almost-inexpensive food choices (try Indian).

Over the years, I was lucky enough to see Rufus Sewell play Septimus in Arcadia by Tom Stoppard (probably the most exciting night of theatre I’ve had), the Royal Shakespeare company and several operas at Covent Garden. I wish they would have fewer Broadway musicals in London – the two cities sometimes seem almost interchangeable (Lion King, Chicago, Chorus Line, etc. etc. etc.—who cares?). But I admit I love to see British plays when they come to the U.S., so I am totally hypocritical on this topic!

Just so this is not an endless list (which it could easily be) or more stuff that sounds too much like bragging, I will conclude My London with another fun pub, worth visiting for its décor as well as its pints. Blackfriar’s Pub is usually jammed. So be prepared to wait for a table. Take along a book!

In closing, I quote the inimitable Dr. Johnson (1709-1784):

“When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford.”

That goes for this woman too!