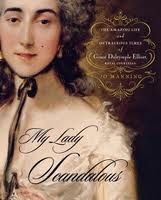

A guest blog by Jo Manning

Jo Manning (with Lily)

The LOOK OF LOVE exhibit has opened in Birmingham, Alabama, at the Birmingham Museum of Art. I was fortunate enough to be there for the opening and the first couple of days of the show, which runs until the end of June. For museum information, click here.

Dr David and Nan Skier

Before discussing this spectacular exhibit – the first of its kind in the world – and one that, with its accompanying catalog, sets the standard for research on this unique portrait miniature-cum-jewelry that has been, up until now, so little known in either the art or jewelry worlds, some backstory…

I often tell people that one never knows, after one’s book is published and sent out into the marketplace, who will see it, who will be affected by it, and what repercussions it will generate. My biography of Grace Dalrymple Elliott, a notorious courtesan of the late 18th-early 19th centuries, was sold in bookstores and museum gift shops.

At one of the latter, the Bass Museum of Art’s gift shop in Miami Beach, Florida, it was seen by Dr David Skier, an eye surgeon from Birmingham, who thought his wife would enjoy it. One of the things he noticed in the book was a sidebar on Lover’s Eyes — eye miniatures – with a photo of a ring in the “collection of the author”.

This was of great interest to Dr Skier because he and his wife Nan had quietly been collecting these beautiful objects for many years and had accumulated some 70+ of them. (They now own 100+ of these miniatures.) Assuming that I had a collection of these objects, they wrote to my publisher Simon & Schuster, asking for my contact information. The publisher referred them to my agent, Jenny Bent of the Bent Agency, and she contacted me. I responded promptly with the news that, no, I owned just the one ring, and that I’d become interested in them after seeing the eye miniatures in the collection of my writing colleague Candice Hern, who owned several lovely brooches. I was also entranced by the story of how they came about and their subsequent history.

The Skiers became friends, and when I was asked to contribute to the catalog for an exhibition of their collection called The Look of Love, I said I would be happy to do so, but that I did not in any way consider myself an expert on the subject. No, they said, we’d like you to write some stories, vignettes, inspired by the eyes in their collection. I thought this was a brilliant idea, frankly, because each of the eyes had a story – an unknown story for the most part, to be sure, as sitters and artists were mostly unidentified – and the eyes do speak to the viewer. I gave my imagination full rein and wrote five stories for their consideration. To my knowledge, this is another first; I know of no fiction in the catalogs of art shows. Essays on the art and history, yes, those are standard, but bits of fiction…nope!

I have to confess that the stories came very easily, which does not always happen to a writer. But the eyes drew me in, and I chose the most eloquent, in my opinion, and wrote away. My goal was to illuminate how these objects of love and affection came about, what they meant in a society with mores quite unlike our own, who the artists might be and why they painted them, what the symbolism involved meant to people in that era, and, yes, the aura they held of clandestine love tokens was very appealing to me, as a writer of historical romance.

The stories are: “Pippa and William”; “Ursula Engleheart Prepares Tea For Her Artist Husband George…”; “I Mourn Your Loss, My Beloved…”; “My Mother, Mariah Norcross”; and “The Grey Eye in Great-Aunt Lavinia’s Jewelry Box”.

Pippa and William are star-crossed lovers (not to be confused with Pippa Middleton and Prince William J) who meet as children, fall in love, but cannot marry because of dynastic “rules” governing marriage; Ursula Engleheart is the story of a prolific painter of miniatures (an estimated 5,000 of them in his lifetime) who paints eyes for clandestine lovers but doesn’t sign them to avoid trouble with his patrons, their parents; I Mourn Your Loss tells a sad tale of two of the many young men who perished in the Napoleonic Wars and how all that remains of one of them is the lover’s eye he gave to his fiancée; My Mother, Mariah Norcross is another bereavement story that also illustrates the perils of epidemics in that Georgian era and its horrific costs to families; and, finally, the last story, of what was found in Great-Aunt Lavinia’s Jewelry Box by careless heirs, speculates on the possible unfortunate fate of many an eye miniature.

The exhibition, and the beautifully illustrated 208 page catalog – a proper coffee-table book! – have each garnered wonderful publicity. The catalog will probably become a collector’s item as well as an important research source on the subject of eye miniatures; the essays by Dr. Graham Boettcher, the curator, and Elle Shushan, a dealer in portrait miniatures, are outstanding, detailed, and most readable.

Graham Boettcher

Elle Shushan

The exhibit is exquisite, mounted with extreme delicacy and care by the professionals at the Birmingham Museum of Art, and the oohs and ahhs of those visiting the jewel of a room in which it is housed brings joy to everyone who’s been involved in its creation and implementation, but most of all to Nan and Dr David Skier, who collected these gorgeous pieces that combine art/history/and jewelry in such a unique manner. Plans are underway to bring the exhibit to other cities; the catalog can be ordered through Amazon, where it has been Number One in its category – Art and Antiques – for weeks. It can also be ordered from the English publisher

Nan Skier talks about the collection

here. Scroll down half a page for the presentation.

There are special events surrounding the Look of Love which can be found on the museum’s web site here.

The coverage has been overwhelming: Take a look at the

Vanity Fair web article, for example,

here.

Many other articles area available on the internet and through the museum’s website.

A postscript: One of the several delightful people I met – including dealers/art consultants/appraisers Reagan Upshaw, Michael Quick, and Sonja Weber (the book is dedicated to her late husband Barry Weber, who often appeared on Antiques Roadshow) — was Thomas Sully, a painter and direct descendant of the English-born American painter of the same name.

Tom Sully self-portrait miniature

Tom Sully paints portrait miniatures, amongst other painting genres and has lately begun to do eye miniatures. I asked him, “How do you do this? Isn’t elephant ivory [which was used for most Georgian eye miniatures] endangered?” He replied that the Russians are selling woolly mammoth – yes! woolly mammoth! – ivory and that is what he is using. Not endangered. Extinct. But not endangered.&

nbsp; I saw some samples of his work and it is very fine, indeed. Check him out here.

And do consider commissioning a lover’s eye – or two – for yourself.