Beginning in London . . . . .

And on to Scotland . . . . .

Louisa Cornell

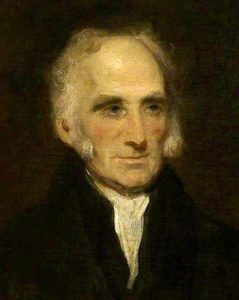

Sir Gilbert Blane

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Sir Gilbert Blane (1749–1843), Physician of the Fleet, argued that the incidence of insanity in the Royal Navy, which he estimated at one in a thousand, was seven times that of the general population. To explain this striking disparity, he identified head injuries, sometimes the result of black powder intoxication in the close confines of warships, together with the shock and blast experienced by gun crews. It was observed that the majority of inmates of a London asylum were seamen who had been sent there after the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. It was theorized that mental illness amongst sailors exposed to combat was possibly related to the phenomenon of wind contusions or tingling, twitching, and even partial paralysis diagnosed in soldiers who had been close to the passage of a projectile or its explosion but had not actually suffered a physical wound.

Click here for a link to the firing of a rolling broadside by the HMS Victory, Nelson’s flagship. The video lasts less than a minute. Imagine hours of this from the inside of a ship. Or imagine seeing this coming at you from another ship in the heat of battle.

During the nineteenth century naval doctors acting as advocates for their patients used mental illness as a criminal defense. Captain G. Scott of the Stately wrote to Nelson on the recommendation of Dr John Snipe to request that the application for a court martial for John Burn, a royal marine, who had struck an officer, be withdrawn on the grounds that the offence was occasioned by insanity. Implicit in this defense was the idea that sailors who had experienced the effects of brutal battles could have their reason disturbed and hence not be fully responsible for their actions.

In 1808, the navy’s lack of provision for clothes for sailors confined in places like Bethlem meant some had only a blanket to wear. Monies had to be dedicated specifically to the care of specific sailors. Situations such as this, once reported to the admiralty, were part of the impetus to establish facilities under the control of the navy and dedicated to the care of those sailors suffering from wounds that could not be seen.

The number of sailors suffering from mental illness was sufficient for the Royal Navy to make special provision for their treatment. Between 1794 and 1818, for example, 1083 officers and ratings were admitted to Hoxton House Asylum, which had been founded in 1695 with Chatham Chest funds to treat naval and government cases. Most of these admissions were then transferred to the Bethlem Hospital at Moorfields for further care, though 364 were regarded as cured. As a Crown institution, Bethlem was obliged to admit patients referred by the Sick and Wounded Seamen’s Office and the War Office.

However, from its opening in 1753,the Royal Hospital at Haslar had admitted psychiatric patients and subsequently Rear Admiral Garrett was reported as saying that a seaman who has lost his reason in the service of the Crown should receive the love and attention on a scale not less than a seaman who has lost a limb in the same cause. In August, 1818 the navy opened a Lunatic Asylum at Haslar. In 1819, wards for soldiers were established at the asylum at Chatham. By the 1820s the emphasis was on moral treatments and patients were encouraged to work in the gardens, take exercise, and undertake tasks in the hospital. Case notes showed that most of those admitted were either psychotic or severely depressed, rather than troubled by the acute effects of battle; most were regarded as incurable.

The naval hospital at Great Yarmouth had been constructed between 1809 and 1811 to treat the sick and wounded of the North Sea Fleet. The Royal Naval Hospital in Yarmouth was also a major hospital for naval lunatics. Taken over by the army in 1844, it housed a Military Lunatic Asylum until the outbreak of the Crimean War when the Admiralty re-acquired the building.

The advantage to facilities established and run by the military were:

Some things to remember:

For records and more insight into the admission of soldiers and sailors into military lunatic asylums check out the section on naval asylums at the British National Archives.

In the 18th century, few people would have been able to swim. It was not the popular sport it is today and it was not taught to children. In 1773, the year before the Society was founded, 123 people were reported to have drowned in London alone. The founders of the Society believed that “several of them might, in all probability, have been restored by a speedy and judicious treatment.” They went on to ask:

“Suppose but one in ten restored, what man would think the designs of the society unimportant, were himself, his relation, or his friend – that one?”

The reward of 4 guineas paid to the rescuer and 1 guinea to anyone allowing a body to be treated on his premises soon gave rise to widespread scam among the down-and-outs of London: one would pretend to be rescued and the other the rescuer – and they would share the proceeds. So monetary rewards were gradually replaced by medals and certificates, with occasional “pecuniary payments” up to a maximum of one guinea.

A network of ‘receiving houses’ was set up in and around the Westminster area of London where bedraggled bodies, many of them pulled out of London’s waterways, could be taken for treatment by volunteer medical assistants. according to Leigh’s New Picture of London 1819 –

This institution was established in 1774, “for recovery of persons apparently drowned or dead.” In l752, Doctor John Fothergill saw the dubiousness and fallacy of the received riteria of dissolution; and, on the subject of covering a man dead in appearance, by distending the lungs with air, he maintained “the possibility of saving many lives, without risking any thing.” Though coming from such excellent authority, the subject attracted no attention at that time, among our countrymen. M. Reaumur communicated, in 1767, to the Academy of Sciences, at Paris, some instances or resuscitation which had occurred in Switzerland. Holland being intersected by numerous canals, &c., its inhabitants were much exposed to accidents by water; and many persons were drowned from the want of proper assistance. Hence, in the year, 1767, a society was formed at Amsterdam which offered premiums to those who saved the life of a citizen in danger of perishing by water. Instigated by this example, the magistrates of health at Milan and Venice issued orders, in 1768, for the treatment of drowned persons. The city of Hamburgh appointed a similar ordinance to be read in all the churches, extending their succour, not merely to the drowned, but to the strangled, to those suffocated by noxious vapours, and to the frozen. In 1771, the magistrates of the city of Paris founded an institution in favour of, the drowned, &c., and there were repeated instances of success in each country. In 1773, Doctor Cogan, in order to convince the British public of the practicability, in many instances, of recovering persons who were apparently dead from drowning, published memoirs of these transactions. No sooner were they translated, than they engaged the humane mind of Dr. Hawes. He ascertained the practicability of thus saving lives, by advertising to reward persons, who, between Westminster and London bridges, should, within a certain time after the accident, rescue drowned persons from the water, and bring them ashore to places appointed for their reception, where means might be used for their recovery, and give immediate notice to him. Many lives were thus saved by himself and other medical men. For twelve months he paid the rewards in these cases; which amounted to a considerable sum. Dr. Cogan remonstrated with him on the injury which his private fortune would sustain from a perseverance in these expenses; and then Dr. Hawes consented to share them with the public. This led to the formation of the London Humane Society; and amongst its first founders were Doctors Goldsmith, Heberden, Lettsom, &c. This happened in the summer of 1774. The object of this society was then, like that at Amsterdam, confined to the recovery of persons who were apparently dead from drowning; but it has since been extended. For the first six years Doctor Cogan prepared the annual reports of the society; nor was Doctor Hawes less attentive in aiding the designs and promoting the views of this institution. The reports were afterwards prepared by Doctor Hawes up to the year of his decease, which occurred in 1808. From that time till 1813, the late Doctor Lettsom undertook the arduous task; and since that time the present registrar and secretary of the society, T. J. Pettigrew, Esq., surgeon extraordinary to the Dukes of Kent and Sussex, has regularly prepared them.

The receiving-houses of this society in Hyde-Park, are admirably accommodated; and handsome rewards in medals and money, are bestowed on those who assist in the preservation or restoration of life. The Hyde Park receiving-house was erected in 1794, on a plot of ground, on the north bank of the serpentine, granted by his Majesty, the patron of the institution, There are eighteen other receiving-houses in and about the metropolis, all of them being supplied with perfect and excellent apparatus.

A farmhouse in Hyde Park was first used as a receiving house and stood on land donated by King George III, the Society’s patron. In 1835, a Receiving House was built in Hyde Park, close to the Serpentine to the plans of architect: J.B. Bunning. The foundation stone was laid by the first Duke of Wellington and the building stood on that spot until its demolition in 1954. The Illustrated London News tells us that the 1835 building was “a neat structure, of fine brick, fronted and finished with Bath and Portland stone. The front has pilasters at the angles, and a neat entablature, which is surmounted by the royal arms upon a pedestal. Over the entrance is a pediment supported by two fluted Ionic columns rod pilasters; upon the entablature is inscribed `Royal Humane Society’s Receiving-house.’ The doorcase is tastefully enriched; over it is sculptured in stone a facsimile of the Society’s metal, encircled with a wreath; the design being a boy endeavouring to rekindle an almost extinct torch by blowing it, and the motto being `Lateat scintillvla forsans’ – `Perchance a spark may be concealed.'”

The Gentleman’s Magazine ran the following piece about the laying of the foundation stone – “The Duke of Wellington laid the first stone of a New Receivinghouse of the Royal Humane Society, on the north bank of the Serpentine River. The old Receiving-house had become much dilapidated, and it is now intended to provide separate apartments for males and females. The fact that during the summer season not less than 200,000 bathers frequent the Serpentine River, and that in one year not less than 231 persons were rescued from impending death through the exertions of the society, induced the Committee to commence the new building, to be paid for from subscriptions which it is hoped will be subscribed for that purpose. The Duke of Wellington arrived precisely at eight o’clock, and was received by the Committee of Management, headed by Mr. R. Hawes, M.P., Colonel Clitheroe, Mr. Alderman Winchester, Mr. Illidge, Sheriff Elect, Mr. Capel, Mr. Brunel, and about 50 other gentlemen connected with the Society. His Grace proceeded at once to the business of the day—the stone to be laid being suspended in the usual manner. Embedded in a thick circular body of glass were the several coins of the present reign, and one of the Society’s Honorary Medals, and in a bottle hermetically sealed, were placed engravings of the intended receiving-house, and these were deposited in the block of stone. His Grace then placed over the cavity a brass plate bearing the following inscription: —” This stone was laid on re-erecting the Receiving-house of the Royal Humane Society, founded by Dr. Hawes and Dr. Cogan in 1774, by his Grace the Duke of Wellington, K.G., Vice-President of the institution, on the 8th day of August, 1834, upon ground granted to the Society by his Majesty George III., and subsequently extended by his Majesty William IV.” On the plate were also engraved the names of the Patrons, the King and the Queen, of the Vice-Patrons, the President, the Treasurer, Secretary, and Architect. The Duke, with a silver trowel, then laid the mortar on the stone, and it was lowered down to its destined spot and squared, the Rev. Charlton Lane delivering a prayer. His Grace and the company present then sat down to a splendid breakfast, Mr. Hawes, M. P., in the chair. The building will be of the Doric order. The design, by Mr. Bunning, of Guilford, was selected after competition, and was shown in the last Exhibition at Somerset House. Messrs. Webb, of Clerkenwell, are the builders.”

Hyde Park was chosen because while tens of thousands of people swam in the Serpentine in the summer, many also used it to ice-skate in the winter. To try to keep the number of drownings to a minimum, the Society employed Icemen to be on hand to rescue anyone going through the ice. Gradually, branches of the Royal Humane Society were set up in other parts of the country, mainly in ports and coastal towns where the risk of drowning was high.

At left is a medal awarded in 1798 to a to Mr Penn, Medical Assistant, for having taken W. Duncan, who is described as having been ‘insensible’, out of the river.

Today the aim of the Society is to recognise the bravery of men, women and children who have saved, or tried to save, someone else’s life. The Society operates solely from its headquarters in London but gives awards to people from all over the country, and sometimes from overseas. Financial rewards are no longer given, but rather medals and certificates. Through the years, the successive Dukes of Wellington have continued to serve on the board of the Society in various capacities.

I have no doubt that each and every Duke of Wellington has also been excessively kind to any stray dogs and cats they may have encountered, as well.

Creevey Papers 1838

December 15th.—Went on Wednesday to a Council at Windsor, and after the Council was invited to stay that night; rode with the Queen, and after riding Melbourne came to me and said Her Majesty wished me to stay the next day also. This was very gracious and very considerate, because it was done for the express purpose of showing that she was not displeased at my not staying when asked on a former occasion, and as she can have no object whatever in being civil to me, it was a proof of her good-nature and thoughtfulness about other people’s little vanities, even those of the most insignificant. Accordingly I remained till Friday morning, when I went with the rest of her suite to see the hounds throw off, which she herself saw for the first time.

The Court is certainly not gay, but it is perhaps impossible that any Court should be gay where there is no social equality; where some ceremony, and a continual air of deference and respect must be observed, there can be no ease, and without ease there can be no real pleasure. The Queen is natural, good-humoured, and cheerful, but still she is Queen, and by her must the social habits and the tone of conversation be regulated, and for this she is too young and inexperienced. She sits at a large round table, her guests around it, and Melbourne always in a chair beside her, where two mortal hours are consumed in such conversation as can be found, which appears to be, and really is, very up-hill work. This, however, is the only bad part of the whole; the rest of the day is passed without the slightest constraint, trouble, or annoyance to anybody; each person is at liberty to employ himself or herself as best pleases them, though very little is done in common, and in this respect Windsor is totally unlike any other place. There is none of the sociability which makes the agreeableness of an English country house; there is no room in which the guests assemble, sit, lounge, and talk as they please and when they please; there is a billiard table, but in such a remote corner of the Castle that it might as well be in the town of Windsor; and there is a library well stocked with books, but hardly accessible, imperfectly warmed, and only tenanted by the librarian: it is a mere library, too, unfurnished, and offering none of the comforts and luxuries of a habitable room.

There are two breakfast rooms, one for the ladies and the guests, and the other for the equerries, but when the meal is over everybody disperses, and nothing but another meal reunites the company, so that, in fact, there is no society whatever, little trouble, little etiquette, but very little resource or amusement. The life which the Queen leads is this: she gets up soon after eight o’clock, breakfasts in her own room, and is employed the whole morning in transacting business; she reads all the despatches, and has every matter of interest and importance in every department laid before her. At eleven or twelve Melbourne comes to her and stays an hour, more or less, according to the business he may have to transact At two she rides with a large suite (and she likes to have it numerous); Melbourne always rides on her left hand, and the equerry in waiting generally on her right; she rides for two hours along the road, and the greater part of the time at a full gallop; after riding she amuses herself for the rest of the afternoon with music and singing, playing, romping with children, if there are any in the Castle (and she is so fond of them that she generally contrives to have some there), or in any other way she fancies.

The hour of dinner is nominally half-past seven o’clock, soon after which time the guests assemble, but she seldom appears till near eight. The lord in waiting comes into the drawing-room and instructs each gentleman which lady he is to take in to dinner. When the guests are all assembled the Queen comes in, preceded by the gentlemen of her household, and followed by the Duchess of Kent and all her ladies; she speaks to each lady, bows to the men, and goes immediately into the diningroom. She generally takes the arm of the man of the highest rank, but on this occasion she went with Mr. Stephenson, the American Minister (though he has no rank), which was very wisely done. Melbourne invariably sits on her left, no matter who may be there; she remains at table the usual time, but does not suffer the men to sit long after her, and we were summoned to coffee in less than a quarter of an hour. In the drawing-room she never sits down till the men make their appearance. Coffee is served to them in the adjoining room, and then they go into the drawing-room, when she goes round and says a few words to each, of the most trivial nature, all however very civil and cordial in manner and expression.

When this little ceremony is over the Duchess of Kent’s whist table is arranged, and then the round table is marshalled, Melbourne invariably sitting on the left hand of the Queen and remaining there without moving till the evening is at an end. At about half-past eleven she goes to bed, or whenever the Duchess has played her usual number of rubbers, and the band have performed all the pieces on their list for the night. This is the whole history of her day: she orders and regulates every detail herself, she knows where everybody is lodged in the Castle, settles about the riding or driving, and enters into every particular with minute attention. But while she personally gives her orders to her various attendants, and does everything that is civil to all the inmates of the Castle, she really has nothing to do with anybody but Melbourne, and with him she passes (if not in tete-a-tete yet in intimate communication) more hours than any two people, in any relation of life, perhaps ever do pass together besides (1) He is at her side for at least six hours every day— an hour in the morning, two on horseback, one at dinner, and two in the evening. This monopoly is certainly not judicious; it is not altogether consistent with social usage, and it leads to an infraction of those rules of etiquette which it is better to observe with regularity at Court. But it is more peculiarly inexpedient with reference to her own future enjoyment, for if Melbourne should be compelled to resign, her privation will be the more bitter on account of the exclusiveness of her intimacy with him. Accordingly, her terror when any danger menaces the Government, her nervous apprehension at any appearance of change, affect her health, and upon one occasion during the last session she actually fretted herself into an illness at the notion of their going out. It must be owned that her feelings are not unnatural, any more than those which Melbourne entertains towards her. His manner to her is perfect, always respectful, and never presuming upon the extraordinary distinction he enjoys; hers to him is simple and natural, indicative of the confidence she reposes in him, and of her lively taste for his society, but not marked by any unbecoming familiarity.

Interesting as his position is, and flattered, gratified, and touched as he must be by the confiding devotion with which she places herself in his hands, it is still marvellous that he should be able to overcome the force of habit so completely as to endure the life he leads. Month after month he remains at the Castle, submitting to this daily routine: of all men he appeared to be the last to be broken in to the trammels of a Court, and never was such a revolution seen in anybody’s occupations and habits. Instead of indolently sprawling in all the attitudes of luxurious ease, he is always sitting bolt upright; his free and easy language interlarded with ‘damns’ is carefully guarded and regulated with the strictest propriety, and he has exchanged the good talk of Holland House for the trivial, laboured, and wearisome inanities of the Royal circle.

1 The Duke of Wellington says that Melbourne is quite right to go and stay at the Castle as much he does, and that it is very fit he should instruct the young Queen in the business of government, but he disapproves of his being always at her side, even contrary to the rules of etiquette; for as a Prime Minister has no precedence, he ought not to be placed in the post of honour to the exclusion of those of higher rank than himself.