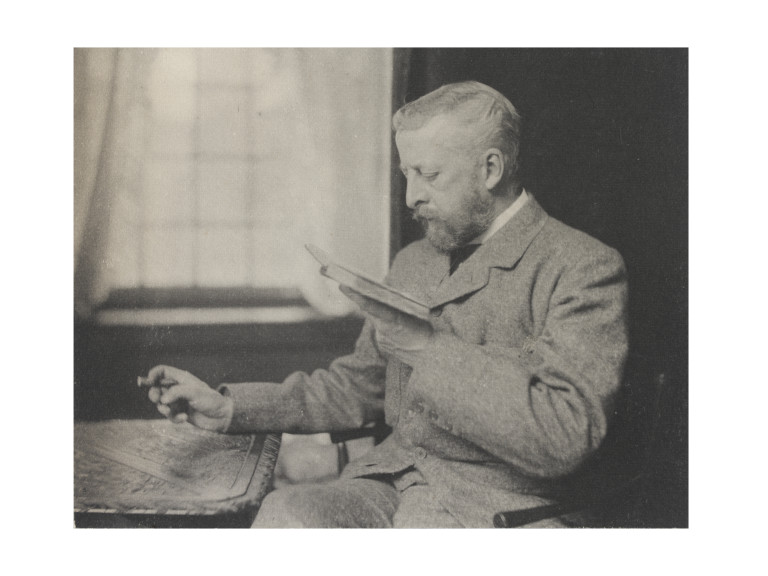

LOUISA CORNELL

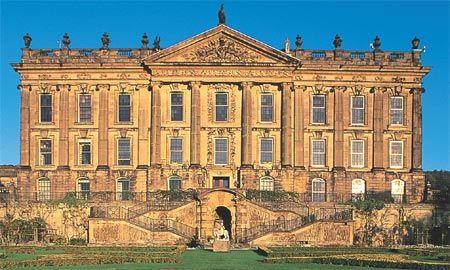

This series of posts will endeavor to explain the different categories and names given to the various historical homes in England. There are specific criteria that define each type of home by the reasons for which it was built and the purpose it served in the lives of those who lived there. However, these designations are not written in stone (pun not really intended,) and they often changed over time based on additions made to them, renovations, architectural design alterations, and changes of ownership. So a manor house could become a stately home or a country house. A castle could become a manor house. A stately home could be called a castle—just ask Castle Howard. Add to that the names by which these homes were known—Chatsworth House, Lyme Park, Shugborough Hall and it can all be a bit confusing. The purpose of this series of posts is to give the reader a sort of guide from which to start when identifying the historic homes of England and perhaps to understand why and when they came to be. Names are important, especially to living, breathing beings, and these marvelous places are indeed very much alive.

The obsession of all three of the authors of this blog with visiting the UK in general and English stately homes in particular is well-documented. If you visit our blog with any frequency I daresay you are as big a fan of English stately homes as we are. One would think any old, elegant, expensive, historic edifice once, and sometimes presently, occupied by a family, usually of aristocratic origins, would be designated a stately home. Perhaps for all intents and purposes that holds true. However, these edifices generally fall into four categories, and only one of those categories is strictly a stately home.

By way of explanation…

What is a stately home?

There are four basic criteria for a mansion like this one to be designated a stately home.

1. Usually built during the 16th, 17th, or 18th centuries (and sometimes the early 19th century) these homes were designed to display the wealth and social status of the owner. In other words, they were showplaces first, a home second.

2. Secondly, the sheer size and grandeur of such an edifice indicates its status as a stately home. They are built on huge estates with extensive grounds. Said grounds are usually set out in large gardens, landscaped woodlands, and designed parks. The houses themselves usually have grand facades, sweeping staircases, and impressive rooms, each designed to strike awe and envy in those who were fortunate enough to be invited to visit by the owners.

3. A third criterion of stately homes would be their architectural style. Some stately homes were inspired by ancient Greek and Roman architecture – all of those Grand Tours no doubt. They can be identified by the classical style, the columns, pediments, and other decorative elements. As with all things fashionable, however, stately homes might also incorporate other architectural styles from Gothic to Baroque to Rococo, depending on what the newest craze of that particular era might be. This also explains why some stately homes exhibit a variety of styles. Each consecutive owner wanted to leave their mark in order to show off both their wealth and their sense of fashion.

4. And fourth, a stately home is defined by its purpose. These homes were built to show off the owner’s wealth, yes, but they were also built to entertain. Some of these owners never visited their stately homes save to throw a ball or a house party in order to support a political cause, aid in a family member’s search for a spouse, conduct an expected seasonal entertainment or other social purpose. They were seldom intended as actual homes. More like a venue for social interactions and grand gestures. That is not to say some families did not occupy these homes for at least part of every year. Some families simply did not care for London life. But the majority spent some time in their country homes and the majority of their time in London or elsewhere.

What is a manor house?

(By the way, I visited Igtham Mote in 1981. It is a spectacular manor house and has been kept as it would have been when built and occupied by the original owner.)

A manor house was built as a home for the lord of the manor who owned most of the land in the surrounding area. Unlike the stately home, the manor house was built primarily as the owner’s residence and as an administration building for the estate. This home was generally the center of economic and social activity for the area.

The criteria for a home to be designated a manor house were:

1. Most manor houses were built in the middle ages, though some were converted into stately homes by those who inherited them.

2. They were generally built in the countryside away from major cities and were surrounded by lands that belong to the owner, lands that were therefore unoccupied save by those who worked the estate as tenants of farm workers.

3. They were built from local materials – stone, timber, or brick whereas stately homes were often built of imported materials.

4. The manor house is a distinctly British architectural style whereas stately homes, castles, and palaces often copied the architectural styles of other countries.

5. A manor house usually was surrounded by a moat. There were fewer rooms in this house than there were in stately homes. The rooms usually included a great hall, living quarters and sleeping rooms for the family, sleeping quarters for the servants, kitchens, and a chapel.

6. The lord of the manor held court there and dealt with disputes dispensed justice where needed. Most of the surrounding land was divided into farms and occupied by tenants who owed their allegiance and much of the profit derived from their endeavors to the lord of the manor.

Are all of those magnificent houses sometimes called stately homes? Of course. However, these houses are more than a label. Each type was built for a specific purpose and in a specific age as a way to mark the history and human progress across Britain.

What about castles, you say? And palaces? And cottages? And… Patience, gentle reader! I will be posting about those specific forms and what makes a castle a castle and why our idea of a cottage does not necessarily mesh with Jane Austen’s idea of a cottage. Stay tuned!

Louisa