This time over to England, I was determined to visit Hatfield House, as it has many connections to the Duke of Wellington via the Cecil family, second cousins to the Duke on his mother’s side, via Emily (nee Mary Amelia), Lady Salisbury, the first Marchioness.

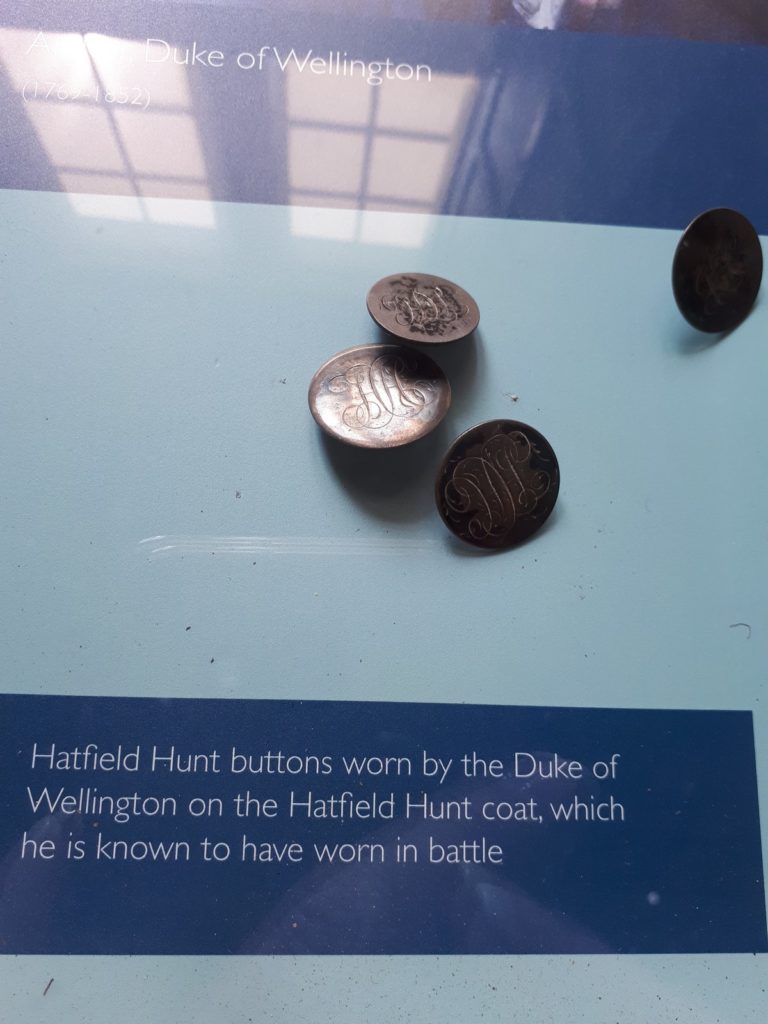

The Duke and Emily were more than cousins, they were good friends. Wellington went often to Hatfield House to dine, to stay, to see the children and to take part in the annual Hatfield Hunt. In fact, it was the light blue Hatfield Hunt coat, gifted to him by Emily herself, that Wellington took to wearing on his various campaigns.

Emily was a fine horsewoman in her own right, the only female regularly welcomed to join hunts at Hatfield and beyond, due in equal part to her riding skills as to her no-nonsense attitude. She rode daily, right up until the day she died. The Duke’s great good friends, Charles and Harriet Arbuthnot, were also frequent guests at Hatfield. In January, 1827, Mrs. Arbuthnot wrote, “We had a large & very pleasant party at Hatfield. Old Lady Salisbury, who is the most wonderful woman that ever was, 78 years old, but riding out on horse back & having apparently none of the infirmaries of age; she tumbled down the stairs the other day, cut herself in various places, but particularly on her leg, which swelled as big as two but to which she wd only apply a lotion used for horses, & went about as if nothing had happened.” Still later, Lady Salisbury’s eyesight began to fail and a groom would accompany her on her daily rides and, it is said, would warn her when approaching a fence by shouting, “Jump, dammit, My Lady, jump!”

In 1834, Harriet Arbuthnot died suddenly of cholera at a farmhouse near the Arbuthnots’ seat, Woodford House, in Northamptonshire. Immediately after her death, her husband, Charles, sent an express message to the Duke at Apsley House. The messenger, however, had to divert to Hatfield House where Wellington was dining with the Dowager Emily and the 2nd Marquess and Marchioness of Salisbury. The following year, Emily died tragically at the age of eighty-five in a fire at Hatfield House. It was thought that feathers in her hat caught alight when she was at her writing-desk and caused the blaze. Her loyal servants frantically attempted to open the door to her room when the fire became evident, but to no avail. The fire destroyed the west wing of the house and only a few bones were found in the rubble.

Emily’s death did nothing to deter the Duke from visiting Hatfield; he remained close to the 2nd Marquess and both of his wives, becoming godfather to several of their children. In addition, Wellington championed the 2nd Marquess’s sister, Emily, Lady Westmeath, during her contentious and much publicized divorce.

So, you see why I wanted to visit Hatfield House. Upon mentioning this to Jacqueline Reiter, she offered to accompany me and Sandra Mettler to Hatfield and to bring her family along. Joy! It turns out that Jacqueline had visited Hatfield House several years ago and informed me that there was a “Wellington Cabinet” in the House, filled with family momentos connected to the Duke. More joy!

On the day, Sandra and I took the train out to Hatfield House from London and met Jacqueline, her husband Miklos and their children, Felix and Julia, at the front gates.

Walking up the drive, we were brought up short by the sight of this contemporary sculpture by Henry Moore in front of the house. Inside, we entered into the Marble Hall.

The embroidered banners hanging from the Gallery feature bees and imperial eagles, symbols of Napoleon. They have recently been copied from originals which were made just before the Battle of Waterloo and meant for Napoleon’s various Departments. After Waterloo, they were instead given to the 2nd Marquess by the Duke of Wellington.

The ceiling’s woodwork and plasterwork are original but colour was added by the 3rd Marquess in 1878, when Jacobean reliefs of the Caesars were replaced with panels featuring classical themes painted by the Italian artist, Giulio Taldini.

The Grand Staircase

The ceiling was decorated for Queen Victoria’s visit to Hatfield in 1846 and has recently been restored so that visitors will be now able to see it in all its glory. At the top, a carving on a newel post shows the figure of a gardener holding a rake. This is said to be John Tradescant, who was sent abroad by Robert Cecil to collect rare and exotic plants for his new garden at Hatfield.

The ceiling of the Long Gallery, originally white, was covered with gold leaf by the 2nd Marquess who had been impressed by a gold ceiling he had seen in Venice.

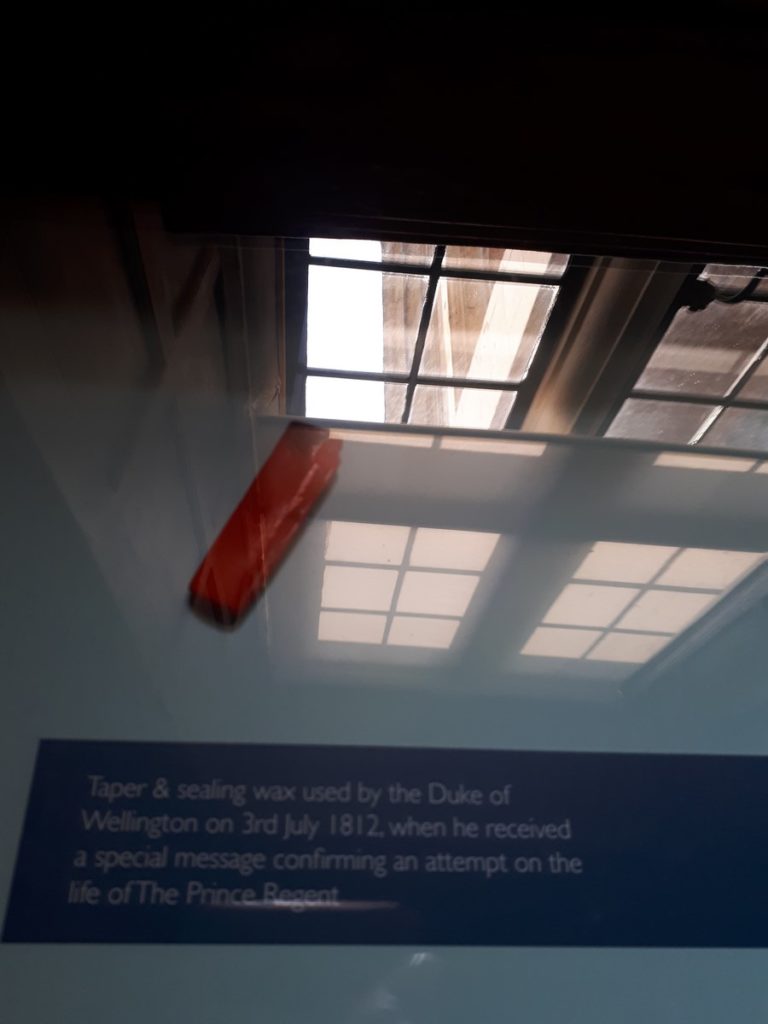

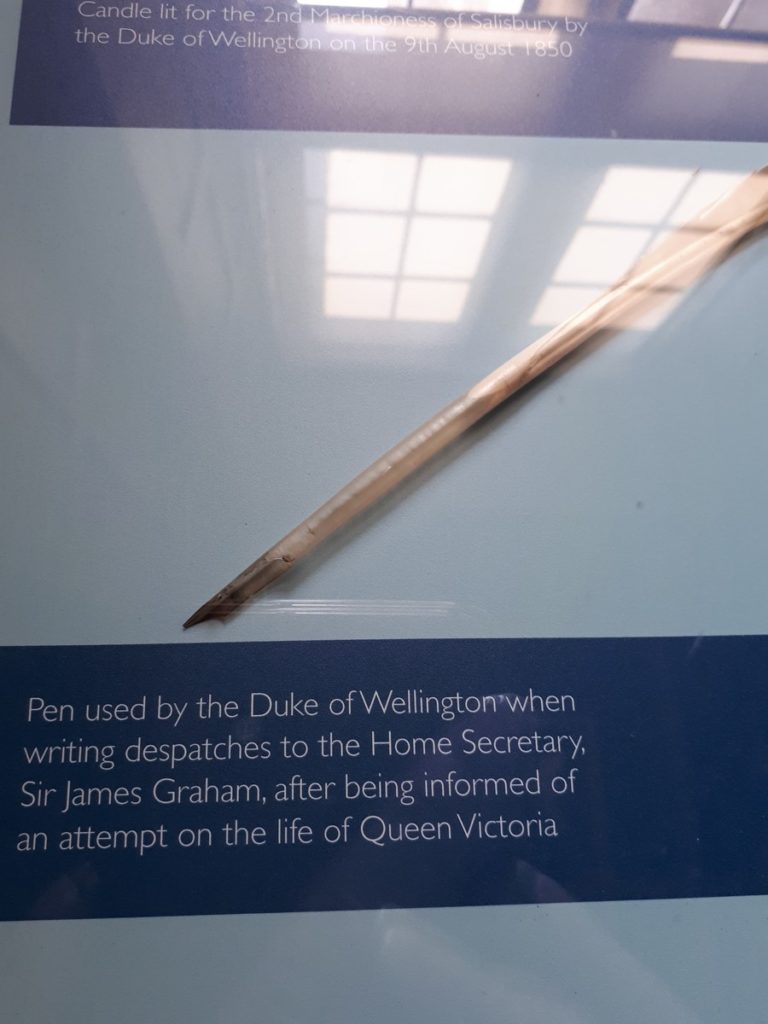

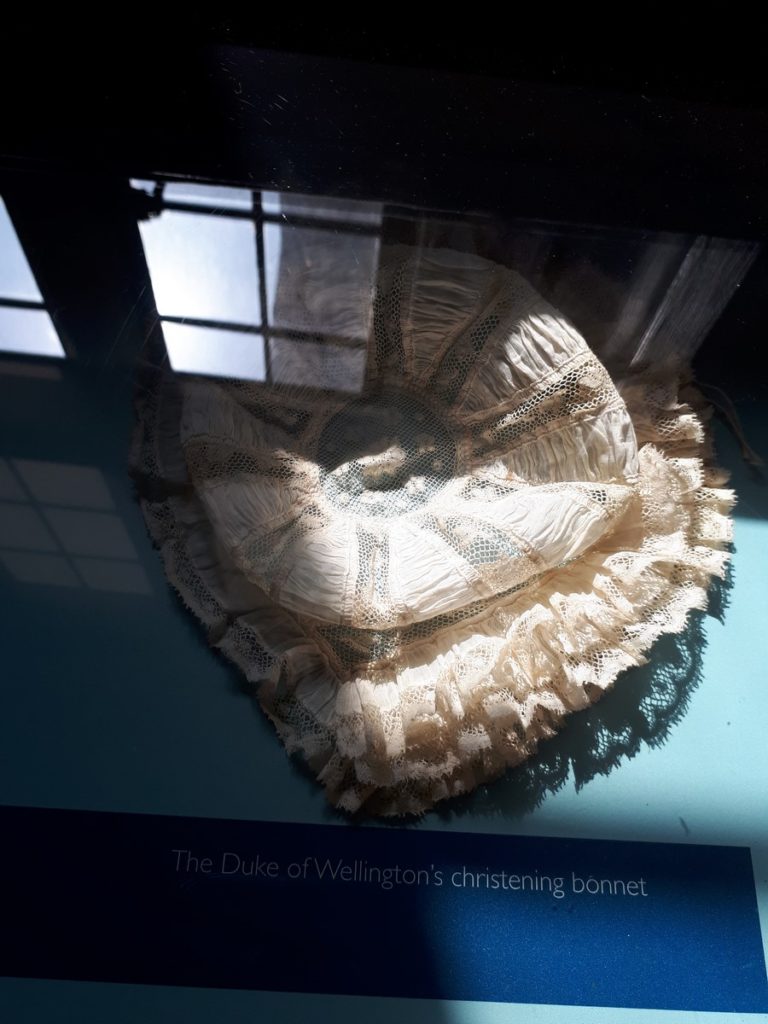

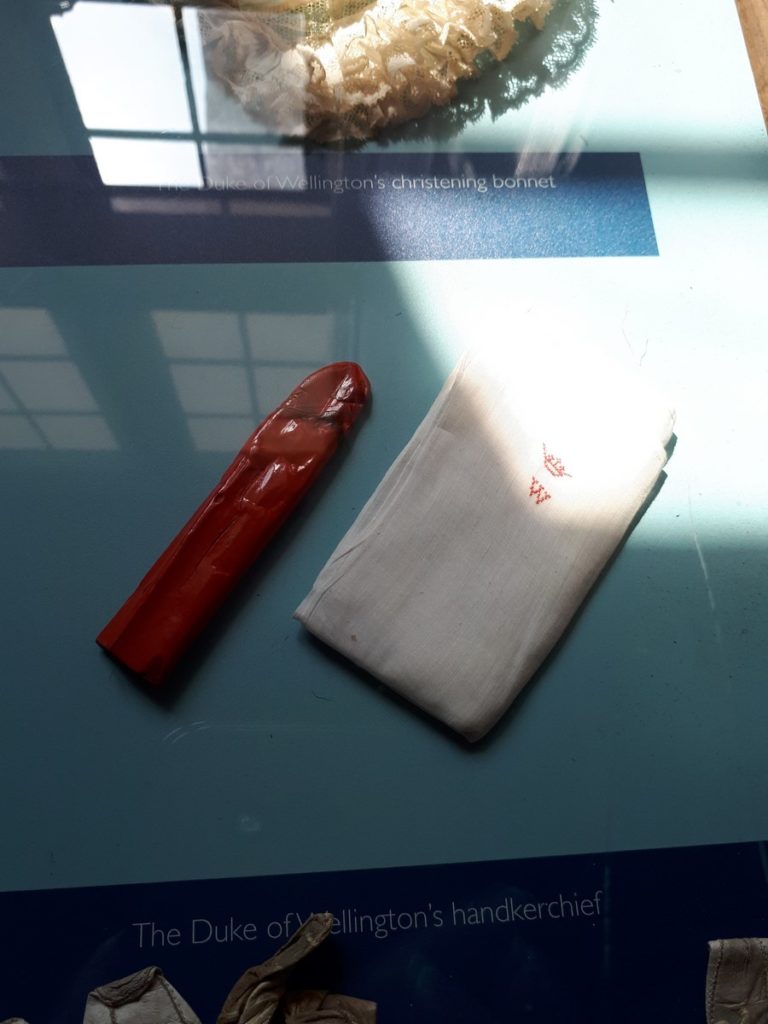

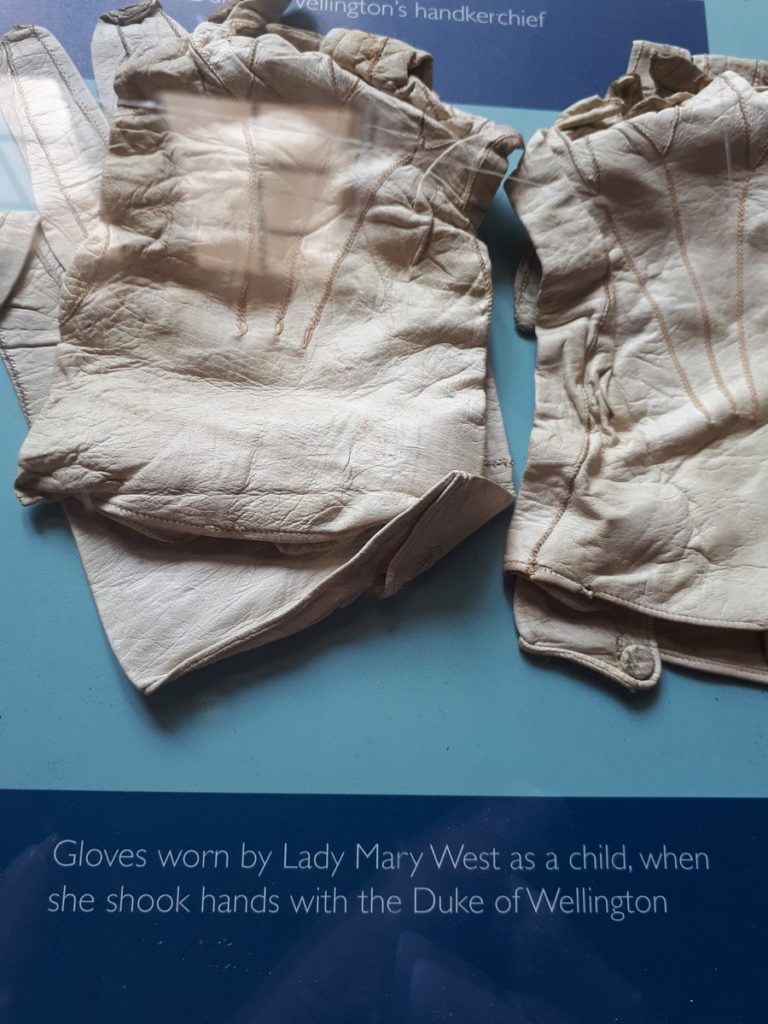

Nearly at the end of our route through the house, we finally came upon the cabinet containing items related to the Duke of Wellington. I’ve been to several other houses that have Wellington items passed down through the family, including Levens Hall in the Lake District, home to Wellington’s niece, Mary Wellesley, who married Sir Charles Bagot. Impressive. In fact, Levens Hall has a dedicated Wellington Trail, directing visitors to all the items associated with the Duke throughout the house. I’ve seen large Wellington collections and I’ve seen small Wellington collections, but I don’t believe I’ve ever seen a collection more charming than that at Hatfield House. One can assume that the Cecil family would have some “wow factor” Wellington items, as evidenced by the Napoleonic flags in the Marble Hall, but what they chose to save and display in this cabinet are items of a far more personal nature.

At the end of our house tour, we stopped for a lunch break and my spirits soared upon seeing this –

and they were dashed when we learned that it was a dog grooming salon.

After lunch, we took Felix and Julia to the farm yard, which they seemed to enjoy. In truth, no one enjoyed it more than me. Baby animals!

Bidding a reluctant goodbye to the Reiters, Sandra and I headed to the rail station, where we discovered that we had enough time for a pint before the next train. The perfect ending to a perfect day.

Would you like to experience a Number One London Tour first-hand? Click here for more details about upcoming Tours.