Many snuff-takers, following the example of Frederick the Great of Prussia, made it a hobby to collect snuff-boxes, Beau Brummell having had a very curious and extensive assortment. On one occasion, when dining at Portman Square, on the removal of the cloth, the snuff-boxes made their appearance, and Brummell’s was particularly admired. It was handed round for inspection, and a gentleman, finding it rather difficult to open, incautiously applied a dessert knife to the lid. Poor Brummell was on thorns. At last he could not contain himself any longer, and, addressing the host, said, with his characteristic quaintness — “Will you be good enough to tell your friend that my snuff-box is not an oyster?”

Beau Brummell also prided himself on his graceful manner of opening the snuff-box with one hand only—the left. Judging from a satirical advertisement which appeared in the Spectator, it would seem that much attention was paid to this act, which afforded an opportunity of displaying the jewelled finger. So important was the act of opening a snuff box that classes were offered:

“The exercise of the snuffbox, according to the most fashionable airs and motions in opposition to the exercise of the fan, will be taught with the best plain or perfumed snuff, at Charles Lillie’s, perfumer, at the corner of Beaufort Buildings, in the Strand, and attendance given for the benefit of the young merchants about the Exchange for two hours every day, at noon, except Saturdays, at a toy-shop, near Garraway’s Coffee House. There will be likewise taught the ceremony of the snuff-box, or rules for offering snuff to a stranger, a friend, or a mistress, according to the degrees of familiarity or distance, with an explanation of the careless, the scornful, the politic, and the surly pinch, and the gestures proper to each of them.”

Another great collector of snuff-boxes was Edward Wortley Montagu, the eccentric son of Lady Mary, who is said to have possessed more boxes than “would suffice a Chinese idol with a hundred noses,” a collection which perhaps was never equalled unless by that of George IV, who was not less extravagant and recherche in snuff and snuff-boxes than in other things.

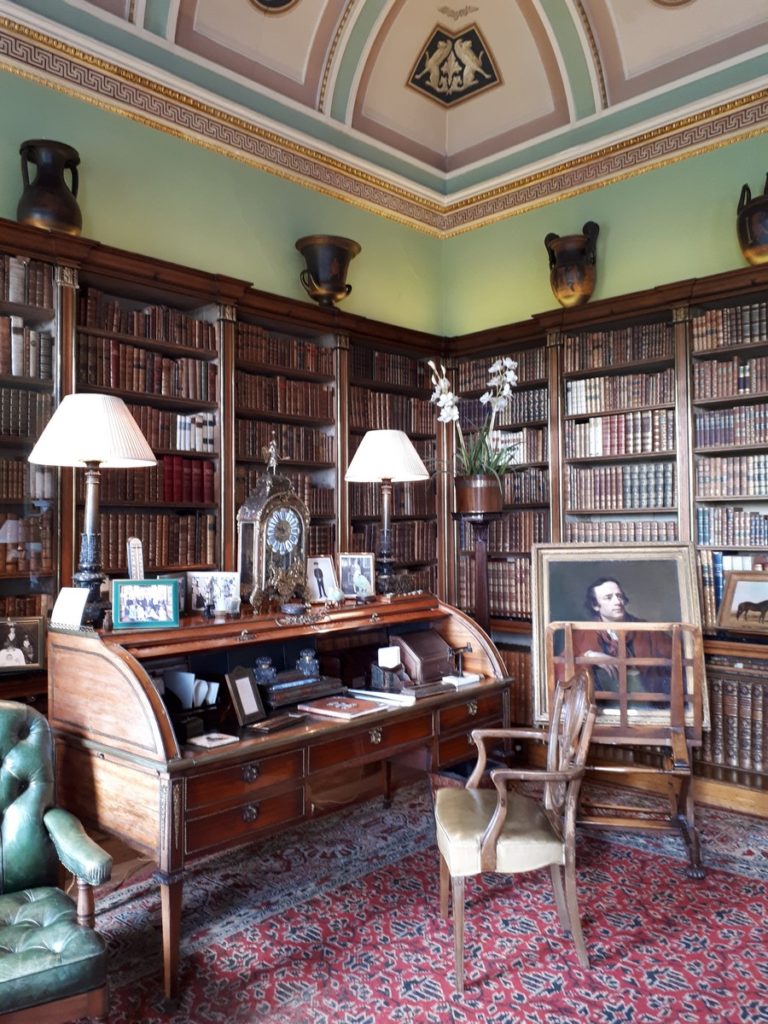

Then there was Lord Petersham, who boasted a stock of snuffs worth three thousand pounds, while he had boxes adapted for all occasions— boxes for winter wear, boxes for summer use. Indeed, the story goes that he had a different box for every day in the year, and Captain Gronow saw him one day use a beautiful Sevres box, which on being admired, he said, “was a nice summer box, but would not do for winter wear.” He was a great connoisseur of snuffs, and “Lord Petersham’s Mixture” has long been proverbial as a popular snuff. He actually devoted one room of his mansion in Whitehall Gardens to properly storing his snuff. That room was a curiosity in its way, with its rows of well-made jars, and proper materials of all kinds for the due admixture, and management, of the snuffs they contained, under the able superintendence of a well-informed man, who was the guardian angel thereof. After the earl’s death the collection was sold, and prices that seem fabulous to the uninitiated were realized for the finer sorts.

Lord Stanhope used to calculate that a regular snuff-taker took one pinch every ten minutes, each pinch, and its accompanying ceremonies, occupying a minute and a half. One minute and a half out of every ten, it has been pointed out, if sixteen hours be allowed to the day, gives two hours and twenty-four minutes per day, or thirty-six and a half days in the year as the time wasted by a snuff-taker upon his nose.

On the other hand, Talleyrand defended snufftaking, not as a habit, but on principle. He maintained that all diplomatists ought to take snuff, as it afforded them an opportunity of delaying a reply which they might not have ready at hand. It further sanctioned, he said, the removal of one’s eyes from those of the interrogator, and occupied the hands, which otherwise might betray a nervous fidget calculated to expose, rather than conceal, his feelings.

Dryden was a snuff-taker, and was in the habit of frequenting Willis’ Coffee House, in Bow Street, Covent Garden, which consequently became one of the leading resorts of the wits of his time. Thus Ned Ward relates in his ” London Spy ” how “a parcel of raw, second-rate beaux and wits were conceited if they had but the honour to dip a finger into Mr. Dryden’s snuff-box.”

The eleventh Earl of Buchan—brother of Thomas Erskine, who by the force of his eloquence rose to be Lord Chancellor of England—was remarkable for his penuriousness, and eccentricity. In the year 1782 the Goldsmiths of Edinburgh presented him with a mounted snuff-box, made from the tree to which William Wallace had once been indebted for his safety. Ten years afterwards, however, Lord Buchan obtained permission from the Goldsmiths to give the snuff-box to Washington, at that time President of the United States. As a reason for so doing he maintained that Washington was the only man in the world to whom he thought the snuff-box justly due.

When a Mrs. Sterne was about to join her husband in Paris, in the year 1762, he wrote:— “You will find good tea upon the road from York to Dover. Only bring a little to carry you from Calais to Paris. Give the Custom-house Officer what I told you. At Calais give more, if you have much Scotch snuff; but, as tobacco is good here, you had best bring a Scotch mull, and make it yourself—that is, order your valet to manufacture it, ’twill keep him out of mischief;” and in another letter he adds, “You must be cautious about Scotch snuff; take half-a-pound in your pocket, and make Lyd do the same.”

When manager of Drury Lane Theatre, Garrick brought into fashion a particular snuff mixture. It appears that a man named Hardham had been his numberer—to count the audience in the theatre—and on inventing his

“mixture,” Garrick rendered him the following service. Whilst enacting the character of a man of fashion on the stage, Garrick offered a pinch of his snuff to a fellow comedian, observing that it was the most fashionable mixture of the day, and to be had only at Hardham’s, 37, Fleet Street. As may be imagined, the puff answered beyond Garrick’s expectation, and for many years afterwards Hardham’s was the favourite mixture, when snuff-taking was the rage and fashion of the time. It may be added that Hardham, having made a large fortune by his snuff trade in Fleet Street, retired to Chichester, where he died in the year 1772, bequeathing a portion of his well-earned wealth to charitable institutions of that city, which, by-the-bye, was his native place.

Sir Joshua Reynolds took snuff so freely when he was painting that it occasionally inconvenienced his sitters. The story goes that when he was painting the large picture at Blenheim of the Marlborough family, the Duchess one day ordered the servant to bring a broom and sweep up Sir Joshua’s snuff from the carpet; but Reynolds, who would not permit any interruption while engaged in his studio, ordered him to let the snuff remain until the completion of his picture, observing that the dust, raised by the broom, would do more injury to his picture than the snuff could possibly do to the carpet.

According to another story, a gentleman told Wilkie he’d sat to Sir Joshua, “who dabbled in a quantity of snuff, laid the picture on its back, shook it about till it settled like a batter-pudding, and then painted away.”