In Britain, the day after Christmas is known as Boxing Day. Every December 26 I wonder what in the world that means — and I never find out for sure. Maybe someone can tell me, Victoria, what it is. Definitively!

Here’s what Wikipedia says: “The exact etymology of the term “boxing day” is unclear. There are several competing theories, none of which is definitive.” This comes after they have already defined Boxing Day as a time when servants get their gifts.

So I turned to Snopes — which says the claim that Boxing Day means it is time to get rid of Christmas boxes is false… so where besides Nordstrom’s do stores have boxes any more?

Snopes goes on: “The holiday’s roots can be traced to Britain, where Boxing Day is also known as St. Stephen’s Day. Reduced to the simplest essence, its origins are found in a long-ago practice of giving cash or durable goods to those of the lower classes. Gifts among equals were exchanged on or before Christmas Day, but beneficences to those less fortunate were bestowed the day after. And that’s about as much as anyone can definitively say about its origin because once you step beyond that point, it’s straight into the quagmire of debated claims and dueling folklorists.”

by Guest Blogger Gina Conkle

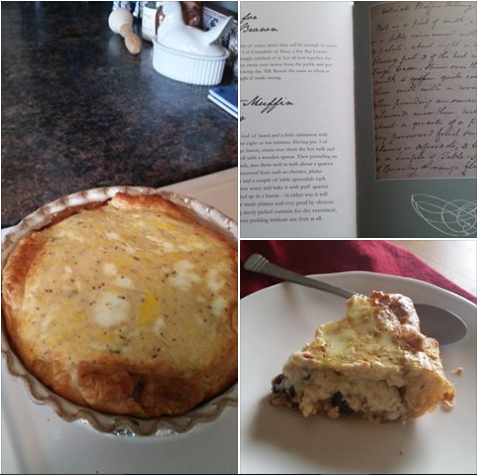

Does pudding make you think sex? Probably not. When someone says “pudding” most people think of the dessert easily made from a box. Its popularity has fallen in favor of cakes, pies, and ice cream.

But once upon a time, pudding was polarizing. Political factions rose up over the food. Laws were debated in England’s Parliament. Citizens clashed (and yes, even rioted!) over the right to feast as they saw fit. Pudding was surprisingly a contentious issue in England’s history. For a time, the dish was on the outs.

Georgian England, thank goodness, recovered their decorum. King George I was served pudding at Christmas dinner and he thought the dish divine. Pudding was back.

But, why all the hubbub over…pudding? Let me explain.

A funny thing happened during Christmas

Medieval England was largely Catholic. Christmas Day was generally somber with Epiphany (the twelve days following Christmas) the time to party big—in many cases with Mardi Gras-esque debauchery. Historically speaking, Mardi Gras actually begins on January 6th (Twelfth Night).

In modern times, that kind of revelry stays in New Orleans. But, imagine what would happen if it cropped up all over? Some would denounce the excess. In early 17th century, many did.

Naughty, sexy pudding

When Oliver Cromwell came to power, Parliament demanded change in England’s Christmas festivities. Pudding was an often-discussed dish. Lawmakers (many of them Puritans) called pudding “lewd” and “unfit for God-fearing people.” Puritans weren’t the only pudding-bashing group. Quakers claimed pudding was “the invention of the scarlet whore of Babylon.”

These groups objected to what went into dessert puddings, brandy being a chief ingredient. Those opposed to pudding felt the food added to drunken, licentious behavior. Of course, we know today high temperatures cook the alcohol, leaving only the flavor. You won’t get drunk on pudding.

But, Cromwellian leadership took the excesses to heart. They banned Christmas. They ordered shops to stay open on Christmas Day. Soldiers patrolled the streets and seized “Christmas feast food” which especially meant sinful pudding!

To be fair, the Scottish Kirk (church) had outlawed Christmas decades earlier. People north and south of the River Tweed were sickened by the gluttony of sins. When Cromwell’s reign ended, Charles II was restored to the English throne. Yet, Christmas and its famed pudding didn’t come roaring back. Citizens worn out from in-fighting didn’t rush to reinstate the old way of celebrating the holiday.

The Complaint of Christmas

It took satirist John Taylor to bring people to their senses. In his pamphlet, The Complaint of Christmas, Taylor decried the “harmless sports” of the holiday which “are now extinct and put out of use… as if they had never been.” He rightfully pointed out “the merry lords of misrule [are] suppressed by the mad lords of bad rule at Westminster.”

Christmas crept back…more like a lamb than a lion, but it was back. In moderation.

It took George I enjoying his first Christmas dinner as England’s monarch to bring pudding again into holiday popularity. The tasty dish was de rigueur!

Here’s to your Christmas feast (with pudding or without).

Gina Conkle writes lush Viking romance and sensual Georgian romance. Her books always offer a fresh, addictive spin on the genre with the witty banter and sexual tension that readers crave. She grew up in southern California and despite all that sunshine, Gina loves books over beaches and stone castles over sand castles. Now she lives in Michigan with her favorite alpha male, Brian, and their two sons where she enjoys recreating recipes from the past.

Gina’s website can be found here and you can also find her on Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest and BookBub. You can also subscribe to Gina’s newsletter for Bonus Reads.

From The Book of Christmas: Descriptive Customs, Ceremonies, Traditions by Thomas Kibble Hervey (1845)

Everywhere, throughout the British Isles, Christmas-eve is marked by an increased activity about the good things of this life. “Now,” says Stevenson, an old writer, “capons and hens, besides turkeys, geese, ducks, with beef and mutton, must all die; for in twelve days, a multitude of people will not be fed a little . . .” The abundant displays of every kind of edible, in the London markets, on Christmas-eve, with a view to the twelve days’ festival, the blaze of lights amid which they are exhibited, and the evergreen decorations by which they are empowered —together with the crowds of idlers or of purchasers that wander through these well-stored magazines—present a picture of abundance, and a congress of faces, well worthy of a single visit from the stranger, to whom a London market, on the eve of Christmas, is, as yet, a novelty.

The approach of Christmas-eve, in the metropolis, is marked by the Smithfield show of over-fed cattle; by the enormous beasts and birds, for the fattening of which medals and cups and prizes have been awarded by committees of amateur graziers and feeders;—in honor of which monstrosities, dinners have been eaten, toasts drunk, and speeches made. These prodigious specimens of corpulency we behold, after being thus glorified, led like victims of antiquity, decked with ribands and other tokens of triumph— or perhaps, instead of led, we should, as the animals are scarcely able to waddle, have used the word goaded—to be immolated at the altar of gluttony, in celebration of Christmas! To admiring crowds, on the eve itself, are the results of oil-cake and turnip feeding displayed, in the various butchers’ shops of the metropolis and its vicinity; and the efficacy of walnut-cramming is illustrated in Leadenhall market,—where Norfolk turkeys and Dorking fowls appear, in numbers and magnitude unrivalled. The average weight given for each turkey, by the statement heretofore quoted by us, of the number and gravity of those birds sentup to London from Norfolk, during two days of a Christmas, some years ago—is nearly twelve pounds; but what is called a fine bird, in Leadenhall Market, weighs, when trussed, from eighteen to one or two-and-twenty pounds,—the average price of which may be stated at twenty shillings; and prize turkeys have been known to weigh more than a quarter of a hundred weight.

Brawn is another dish of this season; and is sold by the poulterers, fishmongers, and pastry-cooks. The supply for the consumption of London is chiefly derived from Canterbury, Oxfordshire, and Hampshire. “It is manufactured from the flesh of large boars, which are suffered to live in a half-wild state, and, when put up to fatten, are strapped and belted tight round the principal parts of the carcass, in order to make the flesh become dense and brawny. This article comes to market, in rolls about two feet long, and ten inches in diameter, packed in wicker baskets.”

Another feature of this evening, in the houses of the more wealthy, was the tall Christmas candles, with their wreaths of evergreens, which were lighted up, along with the Yule log, and placed on the upper table, or dais, of ancient days. Those of our readers who desire to light the Christmas candles, this year, may place them on the sideboard, or in any conspicuous situation.

Our account of Christmas would not be complete,—without giving some description of the forms which attended the introduction of the boar’s head at the feasts of our ancestors. The boar’s head soused, then, was carried into the great hall, with much state; preceded by the Master of the Revels, and followed by choristers and minstrels, singing and playing compositions in its honor. Dugdale relates that at the Inner Temple, for the first course of the Christmas dinner, was ” served in, a fair and large bore’s head, upon a silver platter, with minstrelsye.” At St. John’s, Oxford, in 1607, before the bearer of the boar’s head,—who was selected for his height and lustiness, and wore a green silk scarf, with an empty sword-scabbard dangling at his side,—went a runner, dressed in a horseman’s coat, having a boar’s spear in his hand,—a huntsman in green, carrying the naked and bloody sword belonging to the head-bearer’s scabbard,—and “two pages in tafatye sarcenet,” each with a “mess of mustard.”