If we want to see the good old Christmas— the traditional Christmas—of old England, we must look for it in the country. There are lasting reasons why the keeping of Christmas cannot change in the country as it may in towns. The seasons themselves ordain the festival. The close of the year is an interval of leisure in agricultural regions ; the only interval of complete leisure in the year; and all influences and opportunities concur to make it a season of holiday and festivity. If the weather is what it ought to be at that time, the autumn crops are in the ground; and the springing wheat is safely covered up with snow. Everything is done for the soil that can be done at present; and as for the clearing and trimming and repairing, all that can be looked to in the after part of the winter; and the planting is safe if done before Candlemas. The plashing of hedges, and cleaning of ditches, and trimming of lanes, and mending of roads, can be got through between Twelfth Night and the early spring ploughing; and a fortnight may well be given to jollity, and complete change.

Such a holiday requires a good deal of preparation: so Christmas is, in this way also, a more weighty affair in the rural districts than elsewhere. The strong beer must be brewed. The pigs must be killed weeks before; the lard is wanted; the bacon has to be cured; the hams will be in request; and, if brawn is sent to the towns, it must be ready before the children come home for the holidays. Then, there is the fattening of the turkeys and geese to be attended to; a score or two of them to be sent to London, and perhaps half-a-dozen to be enjoyed at home. When the gentleman,or the farmer,or the country shop-keeper, goes to the great town for his happy boys and girls, he has a good deal of shopping to do. Besides carrying a note to the haberdasher, and ordering coffee, tea, dried fruit, and spices, he must remember not to forget the packs of cards that will be wanted for loo and whist. Perhaps he carries a secret order for fiddlestrings from a neighbour who is practising his part in good time.

There is one order of persons in the country to whom the month of December is anything but a holiday season—the cooks. Don’t tell us of town-cooks in the same breath! It is really overpowering to the mind to think what the country cooks have to attend to. The goose-pie, alone, is an achievement to be complacent about; even the most ordinary goose-pie ; still more, a superior one, with a whole goose in the middle, and another cut up and laid round ; with a fowl or two, and a pheasant or two, and a few larks put into odd corners; and the top, all shiny with white of egg, figured over with leaves of pastry, and tendrils and crinkle-crankles, with a bunch of the more delicate bird feet standing up in the middle. The oven is the cook’s child and slave; the great concern of her life, at this season. She pets it, she humours it, she scolds it, and she works it without rest. Before daylight she is at it—baking her oat bread; that bread which requires such perfect behaviour on the part of the oven! Long lines of oat-cakes hang overhead, to grow crisp before breakfast; and these are to be put away when crisp, to make room for others; for she can hardly make too much. After breakfast, and all day, she is making and baking meat-pies, mince-pies, sausage-rolls, fruit-pies, and cakes of all shapes, sizes, and colours.

And at night, when she can scarcely stand for fatigue, she banks the oven fire, and puts in the great jar of stock for the soups, that the drawing may go on, from all sorts of savoury odds and ends, while everything but the drowsy fire is asleep. She wishes the dear little lasses would not come messing and fussing about, making gingerbread and cheesecakes. She would rather do it herself, than have them in her way. But she has not the heart to tell them so. On the contrary, she gives them ginger, and cuts the citron-peel bountifully for them; hoping, the while, that the weather will be fine enough for them to go into the woods with their brothers for holly and ivy. Meantime, the dairy-woman says, (what she declares every Christmas,) that she never saw such a demand for cream and butter; and that, before Twelfth Night, there will be none. And how, at that season, can she supply eggs by scores, as she is expected to do. The gingerbread baked, the rosiest apples picked out from their straw in the apple-closet, the cats, and dogs, and canary birds, played with and fed, the little lasses run out to see what the boys are about.

The woodmen want something else than green to dress the house with. They are looking for the thickest, and hardest, and knottiest block of wood they can find, that will go into the kitchen chimney. A gnarled stump of elm will serve their purpose best; and they trim it into a size to send home. They fancy that their holiday is to last as long as this log remains; and they are satisfied that it will be uncommonly difficult to burn up this one. This done, one of them proceeds with the boys and girls to the copses where the hollies are thickest; and by carrying his bill-hook, he saves a vast deal of destruction by rending and tearing. The poor little birds, which make the hollies so many aviaries in winter, coming to feed on the berries, and to pop in among the shining leaves for shelter, are sadly scared, and out they flit on all sides, and away to the great oak, where nobody will follow them.

For, alas! there is no real mistletoe now. There is to be something so called hung from the middle of the kitchen ceiling, that the lads and lasses may snatch kisses and have their fun; but it will have no white berries, and no Druidical dignity about it. It will be merely a bush of evergreen, called by some a mistletoe, and by others the Bob, which is supposed to be a corruption of ” bough.” When all the party have got their fagots tied up, and strung over their shoulders, and button-holes, hats, and bonnets stuck with sprigs, and gay with berries, it is time they were going home ; for there is a vast deal to be done this Christmas Eve, and the sunshine is already between the hills, in soft yellow gushes, and not on them.

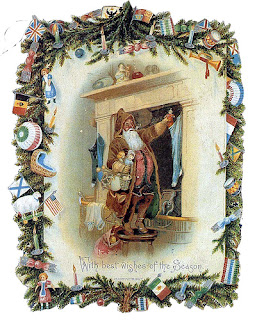

A vast deal there is to be done; and especially if there is any village near. First, there is to dress the house with green; and then to go and help to adorn the church. The Bob must not be hung up till to-morrow: but every door has a branch over it; and the leads of the latticed windows are stuck with sprigs; and every picture-frame, and lookingglass, and c

andlestick is garnished. Any “scraps” (very young children) who are too small to help, pick up scattered holly-leaves, and, being not allowed to go upon the rug, beg somebody to throw them into the fire; whence ensues a series of cracklings, and sputtering blazes, and lighting up of wide-open eyes. In the midst of this—hark ! is not that the church bell? The boys go out to listen, and report that it is so;—the “Christmas deal” (or dole) is about to begin; so, off go all who are able, up to the church.

It is very cold there, and dim, and dreary, in spite of the candles, and the kindness, and other good things that are collected there. By the time the bell has ceased to clang, there are a few gentlemen there, and a number of widows, and aged men, and orphan children. There are piles of blankets; and bits of paper, which are orders for coals. One gentleman has sent a bag of silver money; and another, two or three sheep, cut up ready for cooking; and another, a great pile of loaves. The boys run and bring down a ladder to dress the pillars; and scuffle in the galleries; and venture into the pulpit, under pretence of dressing the church. When the dole is done and the poor people gone, the doors are closed; and, if the boys remain, they must be quiet; for the organist and the singers are ‘going to rehearse the anthem that is to be sung to-morrow. If the boys are not quiet, they are turned out.

There is plenty of bustle in the village. The magistrates are in the long room of the inn, settling justice business. The inn looks as if it were illuminated. The waiters are seen to glide across the hall; and on the steps are the old constable, and the new rural policeman, and the tax-collector, and the postman. It is so cold that something steaming hot will soon be brought for them to drink; and the poor postman will be taken on his weak side. Christmas is a trying season to him, with his weak head, and his popularity, and his Christmas-boxes, and his constant liability to be reported.

Cold as it is, there are women flitting about; going to or from the grocer’s shop, and all bringing away the same things. The grocers give away, this night, to their regular customers, a good mould candle each, and a nutmeg. This is because the women must be up by candle-light to-morrow, to make something that is to be spiced with nutmeg. So a good number of women pass by with a candle and a nutmeg; and some, with a bottle or pitcher, come up the steps, and go to the bar for some rum. But the clock strikes supper-time, and away go the boys home.

Somebody wonders at supper whether the true oval mince-pie is really meant to be in the form of a certain manger; and its contents to signify the gifts, various and rich, brought by the Magi to that manger. And while the little ones are staring at this news, somebody else observes that it was a pretty idea of the old pagans, in our island, of dressing up their houses with evergreens, that there might be a warm retreat for the spirits of the woods in times of frost and bitter winter storms. Some child peeps timidly up at the biggest branch in the room, and fancies what it would be to see some sprite sitting under a leaf, or dancing along a spray. When supper is done, and the youngest are gone to bed, having been told not to be surprised if they should hear the stars singing in the night, the rest of the party turn to the fire, and begin to roast their chestnuts in the shovel, and to heat the elderwine in the old-fashioned saucepan, silvered inside. One absent boy, staring at the fire, starts when his father offers him a chestnut for his thoughts. He hesitates, but his curiosity is vivid, and he braves all the consequences of saying what he is thinking about. He wonders whether he might, just for once, —just for this once—go to the stalls when midnight has struck, and see whether the oxen are kneeling. He has heard, and perhaps read, that the oxen kneeled, on the first Christmas-day, and kept the manger warm with their breath ; and that all oxen still kneel in their stalls when Christmas-day comes in. Father and mother exchange a quick glance of agreement to take this seriously; and they explain that there is now so much uncertainty, since the New Style of reckoning the days of the year was introduced, that the oxen cannot be depended on; and it is not worth while to be out of bed at midnight for the chance. Some say the oxen kneel punctually when Old Christmas comes in; and if so, they will not do it to-night.

This is not the quietest night of the year; even if nobody visits the oxen. Soon after all are settled to sleep, sounds arise which thrill through some who are half-awakened by them, and then, remembering something about the stars singing, the children rouse themselves, and lie, with open eyes and ears, feeling that Christmas morning has come. They must soon, one would think, give up the star theory; for the music is only two fiddles, or a fiddle and clarionet; or, possibly, a fiddle and drum, with a voice or two, which can hardly be likened to that of the spheres. The voices sing, ” While shepherds watch’d their flocks by night ;” and then—marvellously enough.—single out this family of all the families on the earth, to bless with the good wishes of the season. They certainly are wishing to master and mistress and all the young ladies and gentlemen, “good morning,” and ” a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.” Before this celestial mystery is solved, and before the distant twang of the fiddle is quite out of hearing, the celestial mystery of sleep enwraps the other, and lays it to rest until the morrow.

The boys—the elder ones—meant to keep awake; first, for the Waits, and afterwards to determine for themselves whether the cock crows all night on Christmas Eve, to keep all hurtful things from walking the earth. When the Waits are gone, they just remember that any night, between this and Old Christmas, will do for the cock, which is said to defy evil spirits in this manner for the whole of that season. Which the boys are very glad to remember; for they are excessively sleepy; so off they go into the land of dreams.

It is now past two; and at three the maids must be up. Christmas morning is the one, of all the year, when, in the North of England especially, families make a point of meeting, and it must be at the breakfast table. In every house, far and near, where there is fuel and flour, and a few pence to buy currants, there are cakes making, which everybody must eat of; cakes of pastry, with currants between the layers. The grocer has given the nutmeg; and those who can afford it, add rum, and other dain

ties. The ladies are up betimes, to set out the best candlesticks, to garnish the table, to make the coffee, and to prepare a welcome for all who claim a seat. The infant in arms must be there, as seven o’clock strikes. Any married brother or sister, living within reach, must be there, with the whole family train. Long before sunrise, there they sit, in the glow of the fire and the glitter of candles, chatting and laughing, and exchanging good wishes.

In due time, the church-bell calls the flock of worshippers from over hill, and down dale, and along commons, and across fields: and presently they are seen coming, all in their best,—the majority probably saying the same thing,—that, somehow, it seems always to be fine on Christmas-day. Then, one may reckon up the exceptions he remembers; and another may tell of different sorts of fine weather that he has known; how, on one occasion, his daughter gathered thirty-four sorts of flowers in their own garden on Christmas-day; and the rose-bushes had not lost their leaves on Twelfth Day; and then the wise will agree how much they prefer a good seasonable frost and sheeted snow like this, to April weather in December.

Service over, the bell silent, and the sexton turning the key in the lock, off run the young men, out of reach of remonstrance, to shoot, until dinner at least,—more probably until the light fails. They shoot almost any thing that comes across them, but especially little birds,— chaffinches, blackbirds, thrushes,—any winged creature distressed by the cold, or betrayed by the smooth and cruel snow. The little children at home are doing better than their elder brothers. They are putting out crums of bread for the robins, and feeling sorry and surprised that robins prefer bread to plumpudding. They would have given the robins some of their own pudding, if they had but liked it.

In every house, there is dinner to-day,—of one sort or another,—except where the closed shutter shows that the folk are out to dinner. The commonest dinner in the poorer houses —in some parts of the country—is a curious sort of mutton pie. The meat is cut off a loin of mutton, and reduced to mouthfuls, and then strewed over with currants or raisins and spice, and the whole covered in with a stout crust. In some places, the dinner is baked meat and potatoes: in too many cottages, there is nothing better than a morsel of bacon to flavour the bread or potatoes. But it may be safely said that there is more and better dining in England on Christmas-day than on any other day of the year.

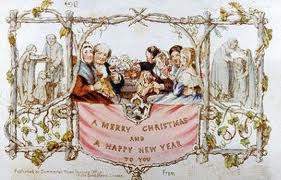

In the houses of gentry and farmers, the dinner and dessert are a long affair, and soon followed by tea, that the sports may begin. Everybody knows what these sports are, in parlour, hall, and kitchen :—singing, dancing, cards, blind-man’s buff, and other such games; forfeits, ghost-story telling, snap-dragon;— these, with a bountiful supper interposed, lasting till midnight. In scattered houses, among the wilds, card-playing goes on briskly. Wherever there are Wesleyans enough to form a congregation, they are collected at a tea-drinking in their chapel; and they spend the evening in singing hymns. Where there are Germans settled, or any leading family which has been in Germany, there is a Christmastree lighted up somewhere. Those Christmastrees are as prolific as the inexhaustible cedars of Lebanon. Wherever one strikes root, a great number is sure to spring up under its shelter.

However spent, the evening comes to an end. The hymns in the chapel, and the carols in the kitchen, and the piano in the parlour are all hushed. The ghosts have glided by into the night. The forfeits are redeemed. The blind-man has recovered his sight, and lost it again in sleep. The dust of the dancers has subsided. The fires are nearly out, and the candles quite so. The reflection that the great day is over, would have been too much for some little hearts, sighing before they slept, but for the thought that to-morrow is Boxing Day; and that Twelfth Night is yet to come.

But, first, will come New Year’s Eve, with its singular inconvenience (in some districts) of nothing whatever being carried out of the house for twenty-four hours, lest, in throwing away anything, you should be throwing away some luck for the next year. Not a potatoparing, nor a drop of soap-suds or cabbagewater, not a cinder, nor a pinch of dust, must be removed till New Year’s morning. In these places, there is one person who must be stirring early—the darkest man in the neighbourhood. It is a serious thing there to have a swarthy complexion and black hair; for the owner cannot refuse to his acquaintance the good luck of his being the first to enter their houses on New Year’s day. If he is poor, or his time is precious, he is regularly paid for his visit. He comes at daybreak, with something in his hand, if it is only an orange or an egg, or a bit of ribbon, or a twopenny picture. He can’t stay a minute,—he has so many to visit; but he leaves peace of mind behind him. His friends begin the year with the advantage of having seen a dark man enter their house the first in the New Year.

Such, in its general features, is Christmas, throughout the rural districts of Old England. Here, the revellers may be living in the midst of pastoral levels, all sheeted with snow; there, in deep lanes, or round a village green, with ploughed slopes rising on either hand: here, on the spurs of mountains, with glittering icicles hanging from the grey precipices above them, and the accustomed waterfall bound in silence by the frost beside their doors; and there again, they may be within hearing of the wintry surge, booming along the rocky shore; but the revelry is of much the same character everywhere. There may be one old superstition in one place, and another in another ; but that which is no superstition is everywhere;—the hospitality, the mirth, the social glow which spreads from heart to heart, which thaws the pride and the purse-strings, and brightens the eyes and affections.

Merry Christmas!

I ordered an amaretto and Vicky had a glass of prosecco. Once again, Venetian hospitality was on display in the form of the unexpected olives, biscotti and cookies that accompanied our drinks.

I ordered an amaretto and Vicky had a glass of prosecco. Once again, Venetian hospitality was on display in the form of the unexpected olives, biscotti and cookies that accompanied our drinks.

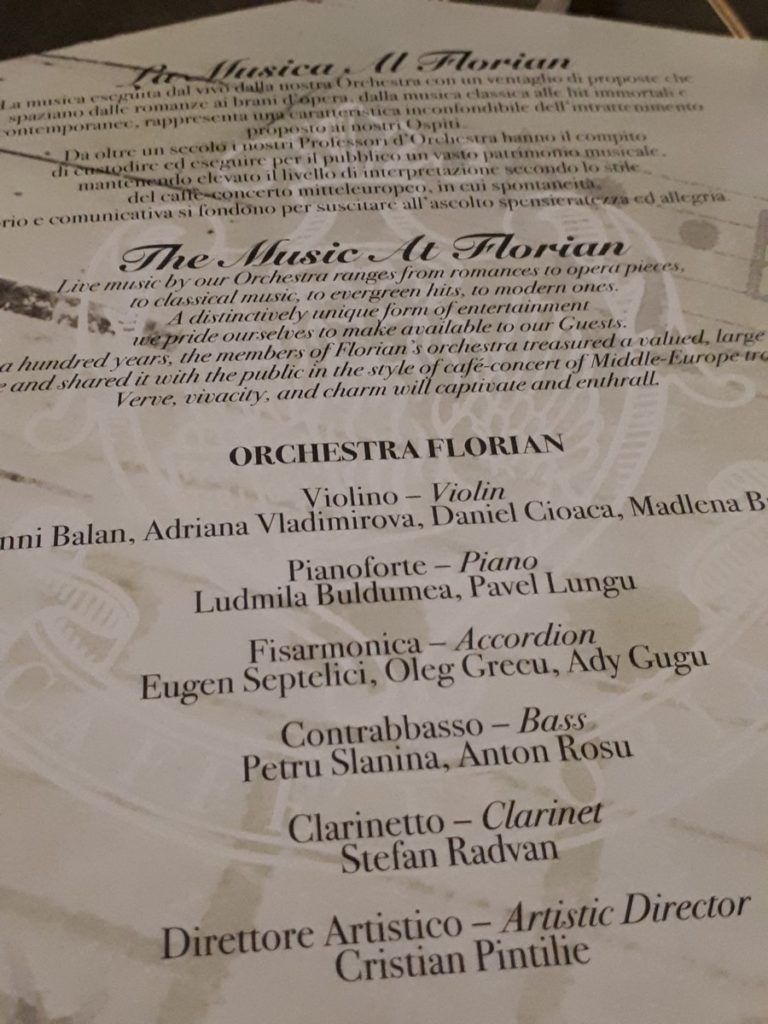

You can listen to the band in this video I took on the night –

You can listen to the band in this video I took on the night –

Feeling in need of a drink, Vicky and I headed to the terrace bar and, as we were in Venice, ordered two glasses of prosecco. Which were served to us along with nuts, crisps and canapes. Very civilized, indeed.

Feeling in need of a drink, Vicky and I headed to the terrace bar and, as we were in Venice, ordered two glasses of prosecco. Which were served to us along with nuts, crisps and canapes. Very civilized, indeed.