Louisa Cornell

By the late 18th century, a new species of rat had invaded England. The brown or “Norway” rats were much larger and quite frankly more frightening than the common black rat indigenous to England. Catching and eliminating rats was considered the perfect job for the poorer citizens of England, especially those people born and bred in the poorer areas of larger cities like London, Manchester, and Edinburgh. After all, these were the people who spent their childhoods playing with rats in the floorboards of their meager homes.

The more successful rat-catchers used ferrets and dogs to catch rats. They were paid per rat and sending a dog into the sewers and less clean and accessible parts of homes and businesses was less work, for the rat-catcher at least. The dogs used for this task were mostly terrier-type dogs. Their prey drive, ferocity, small size and quickness made them perfectly suited for the task.

Some of the breeds used as ratters were:

Bull Terriers

Bedlington Terriers

Fox Terriers

Jack Russell Terriers

Rat Terriers

Black and Tan Terriers

Manchester Terriers

Yorkshire Terriers

Staffordshire Bull Terriers

Those who used and bred dogs for this purpose kept close track of their dogs’ pedigrees. They sought to bred in those traits best suited to ratters and the breed out unwanted qualities. Surprisingly, even those poorest and least educated breeders of rat-catching dogs took great pride in the breeding and pedigrees of their dogs. Having a dog related to some of the better-known ratters was a source of pride, not to mention a great selling point when seeking employment, especially in the more successful businesses and in the more exclusive homes in London.

How did dogs gain reputations as champion ratters? From the late 18th into the early 19th centuries word-of-mouth was a big part of spreading a dog’s fame. However, rat-catchers didn’t only breed dogs, they also bred rats. They bred rats for three purposes.

- Frankly, they bred them to encourage repeat customers or to persuade customers to avail themselves of the rat-catcher’s services. Yes, they bred rats to turn loose in businesses and houses to drum up business.

- They bred them to demonstrate their dogs’ prowess as rat catchers. They gave demonstrations and eventually, once other baiting sports were banned in 1835 by Parliament’s passing of the Cruelty to Animals Act, rat baiting contests took place in the facilities formerly used for cock-fighting, dog fighting and bear baiting. Thousands of rats were needed for these contests and ratters provided them.

- They bred rats for unique colors to sell them to the gentry and aristocrats as pets. Yes, even young Queen Victoria had pet rats, but people were keeping rats as pets long before she did. One of the most famous breeders of pet rats was also one of England’s most famous rat catchers. Jack Black styled himself as rat catcher to Queen Victoria. He was also written up in Henry Mayhew’s 1815 book London Labor and the London Poor. He dressed rather elegantly for a rat catcher in order to drum up business. He was the first recorded breeder of fancy rats and also provided rats for rat baiting contests.

Rat catching dogs made money for their owners both in catching and eliminating rats for customers and in participating in rat baiting contests which involved cash prizes for the winning dogs and, of course, wagering on the outcome of the contests.

These dogs were highly prized by their owners both for their ability to kill rats for customers and by 1835 for their ability in the rat baiting ring. I daresay their lot in life was better than that of turnspit dogs in spite of the very real danger of possible injury and even death when catching rats. These dogs were doing what they were born and bred to do.

One of the most celebrated ratters of his day was the 26-pound bull terrier, Billy, owned by Charles Dew.

The October 1822, edition of The Sporting Magazine provide us with descriptions of two rat pit matches with Billy.

Thursday night, Oct. 24, at a quarter before eight o’clock, the lovers of rat killing enjoyed a feast of delight in a prodigious raticide at the Cockpit, Westminster. The place was crowded. The famous dog Billy, of rat-killing notoriety, 26 lb. weight, was wagered, for 20 sovereigns, to kill 100 rats in 12 minutes. The rats were turned out loose at once in a 12-foot square, and the floor whitened, so that the rats might be visible to all. The set-to began, and Billy exerted himself to the utmost. At four minutes and three-quarters, as the hero’s head was covered with gore, he was removed from the pit, and his chaps being washed, he lapped some water to cool his throat. Again, he entered the arena, and in vain did the unfortunate victims labor to obtain security by climbing against the sides of the pit, or by crouching beneath the hero. By twos and threes, they were caught, and soon their mangled corpses proved the valor of the victor. Some of the flying enemy, more valiant than the rest, endeavored by seizing this Quinhus Flestrum of heroic dogs by the ears, to procure a respite, or to sell their life as dearly as possible; but his grand paw soon swept off the buzzers, and consigned them to their fate. At seven minutes and a quarter, or according to another watch, for there were two umpires and two watches, at seven minutes and seventeen seconds, the victor relinquished the glorious pursuit, for all his foes lay slaughtered on the ensanguined plain. Billy was then caressed and fondled by many; the dog is estimated by amateurs as a most dextrous animal; he is, unfortunately, what the French Monsieurs call borg-ne, that is, blind of an eye. This precious organ was lost to him some time since by the intrepidity of an inimical rat, which as he had not seized it in a proper place, turned round on its murderer, and deprived him by one bite of the privilege of seeing with two eyes in future. The dog BILLY, of rat-killing notoriety, on the evening of the 13th instant, again exhibited his surprising dexterity; he was wagered to kill one hundred rats within twelve minutes; but six minutes and 25 seconds only elapsed, when every rat lay stretched on the gory plain, without the least symptom of life appearing.’ Billy was decorated with a silver collar, and a number of ribband bows, and was led off amidst the applauses of the persons assembled.

Henry Alken

1823

Billy’s best competition results are: (Yes, they kept meticulous records of this.)

Date Rats killed Time Time per rat

1820–??-?? 20 1 minute, 11 seconds 3.6 seconds

1822-09-03 100 8 minutes, 45 seconds 5.2 seconds

1822-10-24 100 7 minutes, 17 seconds 4.4 seconds

1822-11-13 100 6 minutes, 25 seconds 3.8 seconds

1823-04-22 100 5 minutes, 30 seconds 3.3 seconds

1823-08-05 120 8 minutes, 20 seconds 4.1 seconds

Billy’s career was crowned on 22 April 1823, when a world record was set with 100 rats killed in five and a half minutes. This record stood until 1862, when it was claimed by another ratter named “Jacko”. Billy continued in the rat pit until old age, reportedly with only one eye and two teeth remaining.

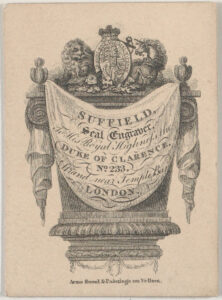

John Suffield was an engraver and desiger of lettering, although he was also known through his signed metal work and made a medal commemorating the election of Sir Charles Cockerell to Evesham in 1819. Suffield is also listed in the 1817 Johnstone’s London Commercial Giude, and Street Directory.

John Suffield was an engraver and desiger of lettering, although he was also known through his signed metal work and made a medal commemorating the election of Sir Charles Cockerell to Evesham in 1819. Suffield is also listed in the 1817 Johnstone’s London Commercial Giude, and Street Directory.