Mention of venerable London auction houses invariably brings to mind Christie’s, in King Street. But there was another auction firm who held some of the most anticipated, and most unique, auctions in the City. The London firm of auctioneers known as Phillips and Son of 73, New Bond Street, was founded by Harry Phillips in 1796. Phillips died in October of 1839 at his house at Worthing, age 73, and was succeeded by his son, who, with his son, son-in-law, and Mr. Frederick Neale, carried on the business of fine art and general auctioneers. Amongst some of the more important art sales by this firm were: The Beckford Collection at Fonthill Abbey, Sir Simon Clarke’s engravings; a thirty-days’ sale of engravings from Paris; the Duke of Buckingham’s engravings, in 1830; Duke of Lucca’s Collection, in 1841; the Count de Morny’s Collection, in 1848; Lady Blessington’s property, in 1849; Lord Northwick’s pictures, in 1859; the Marquis of Hastings’ pictures, books, and engravings, in 1869; Sir Charles Rushout’s pictures and engravings in 1880, including a small collection of about one hundred examples by Bartolozzi (many duplicates) in a folio, which sold for 225 guineas. Another lot in the same sale, containing ninety-eight prints by Bartolozzi and school, sold for 174 guineas.

A book titled Art Sales of 1891 sheds some light on what the going rates for auction houses of that day were – The commissions charged are 7 per cent, on pictures, plate, jewels, porcelain, wine and effects, sculpture, and modern drawings, and 12 per cent, on engravings, books, manuscripts, sketches, coins, medals, antique gems, and old drawings, 5 per cent, being charged on unsold or bought-in lots under £100, and 2 percent, exceeding that sum. For furniture at private houses or in the country the charge is 10 per cent. There is no charge for making valuations for probate if the property is subsequently sold by auction. To secure a day at Messrs. Christie’s, application must be made some months beforehand, and Saturdays in the season are allotted only to exceptionally fine collections.

Still, many of those who had their property sold by auction were in no position to balk at the terms, as they were either badly in hock to creditors or deceased, as evidenced by the following piece which ran in The Gentleman’s Magazine 1805 – Mr. Phillip Auction-room, New Bond-street, was crowded with nobility and persons of distinction. After the sale of several choice lots of china, statues, and Mr. Phillips stated the conditions of sale of the elegant house and furniture, in Hill-street, Berkeley-square, belonging to Mr. Robert Heathcote. The auctioneer referred to the printed particulars, which were in the hands of the company, for the minute description of this elegant mansion, held under a lease from Earl Berkeley, for an unexpired term of 30 years, at a ground rent of 11 l. 7 s. 6d.; and, he stated, that the cost to Mr. Heathcote had been as follows: For the lease, £6000. to Mr. Cundy, the architect, whose taste and judgment had been so conspicuously displayed in the new arrangement and fitting-up of the house, and particularly in the erection of the new and superb library . . . After stating, that every article in Mr. Heathcote’s house at present, except plate, jewels, linen, books, pictures, wines, china, glass-ware, and apparel, would go to the purchaser, the biddings commenced with 1, 000 guineas, on which several advances we’re made from different parts of the room, till they got up to £10,000, when the contest lay entirely between two gentlemen, who were rather tardy in their advances of 50 and 100 guineas at a time, till at length it was knocked down to P. Phillips, esq.

Another entry reads –

Furniture Of Napoleon—On Wednesday a sale by auction of the property of the late Sir Hudson Lowe, including some portion of the furniture which was in the possession of the Emperor Napoleon at St. Helena, took place at the auction rooms of Mr. Phillips, by order of the executors of Sir Hudson Lowe. These consisted of about twenty lots, and among them were a large mahogany frame indulging chair, banded with ebony, on castors, from the Emperor’s study, 15/. 5s.; a small circular mahogany pillar and claw table, on which Napoleon burnt pastiles, 61. 6s.; a six-foot pedestal library table, formed of mahogany and yew tree, on which table he almost always wrote, 18. 18s.; an ebonied arm chair, with cane seat and back, formed of common materials (there was a hole in the cane seat which had been caused by being constantly used, and it was stated by some brokers in the room not to be worth 1s. 6.) From the chair being light it was carried about by the Emperor when he took his walks M Longwood. It was bought for £6.

One sale that was the destined to be the auction of the year, if not the decade, was that of Fonthill Abbey, owned by William Beckford, the author of Vathek. Beckford had commissioned architect James Wyatt to design the Abbey and very few people were invited inside whilst Beckford resided there. For a complete look at both Beckford and the auction we turn to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction –

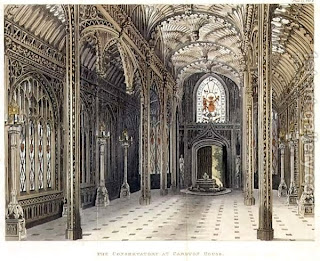

One sale that was the destined to be the auction of the year, if not the decade, was that of Fonthill Abbey, owned by William Beckford, the author of Vathek. Beckford had commissioned architect James Wyatt to design the Abbey and very few people were invited inside whilst Beckford resided there. For a complete look at both Beckford and the auction we turn to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction – THE LATE WILLIAM BECKFORD. From the newspapers we learn that the author of “Vathek” is no more. He died last week at Bath, where he had erected a singular edifice, in some respects a miniature of his former abode, the far-famed Fonthill Abbey.

Beckford squandered his money in the most reckless manner, and at his bidding Fonthill arose, one of the wonders of the world. He bought Gibbon’s library, and left it locked up at Lausanne, and the reason he gave for the purchase was that he might have some books to read when he happened to visit that town. It was not the splendour of Fonthill Abbey —though that was great—nor the value of its contents—though on these immense sums had been expended—that fixed public attention on Fonthill Abbey, so much as the habits of the proprietor, exaggerated, and, in all probability, misrepresented, by report. He was said to see no company, to allow no approach— but to live in almost regal state. Though he had servants fitting his opulence, his favourite was understood to be a dwarf, called Pero. Mr. Beckford was described to be violent. He would speak harshly, or more than speak, to a

servant or a villager that came in his way, but, soon relenting, it was his care nobly to recompense the party he had outraged. It was shrewdly suspected that some of those who experienced the throb of his impetuous anger had artfully put themselves in the way of it, for the sake of the healing donation which was likely to follow.

He certainly lived in seclusion for a number of years, and objected to the abbey being shown to the curious. It was even said, George IV, when Prince of Wales, had intimated a wish to visit it, which had been met by something like a refusal. Be this as it may, it got wind among the public that the residence of Mr. Beckford was “a sealed book;” and when, in 1822, the news burst on the town that the abbey and all its contents were about to be on public view, preparatory to a sale by auction, every one was anxious to see the Palace of Wonders. It was likened to throwing open the blue-room of Bluebeard.

It is not surprising that so eccentric a man excited the popular wonder, and that when in consequence of the depreciation of his West India property he decided to sell Fonthill via an auction conducted by Mssrs. Christie, the public excitement was intense: Fonthill, which had been talked about by the whole nation but only seen by a very few. This was in 1822. Seven thousand two hundred catalogues were sold at a guinea each to those who wished to see the place. However, it was not disposed of by Mr. Christie at public auction, but sold en masse to Mr. John Farquhar for £330,000. Beckford reserved, however, some of his choicest books, pictures, and curiosities.

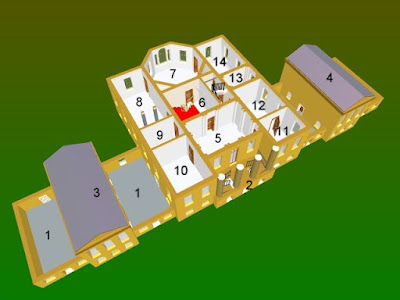

The whole property had been bought by the late Mr. H. Phillips for a Mr. Farquhar, a Scotsman, of very penurious habits, who had mode a vast fortune in India, but who continued to dress and to live in the meanest style. He bought this palace and park, not because, like old Scrooge, a dream had induced him to rush from grinding parsimony to openhearted benevolence, but because it appeared a good opportunity for increasing his store, aided by the experience and talent of the Bond-street auctioneer. It is true he took up his abode in it for a time, but he bought it not to inhabit, but to sell, and accordingly it was announced in the following year that the whole, as the phrase is, was to be brought to the hammer. The ensuing sale occupied thirty-seven days.

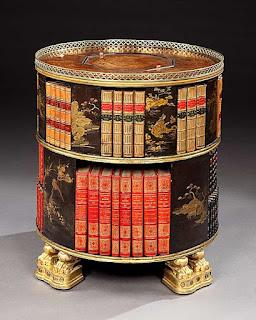

Mr. Beckford’s library was very extensive, yet, among the countless ranges of books which he possessed, he had so extraordinary a memory, that he could at once indicate the shelf, and the part of the shelf, on which any particular volume might he found. This was proved, to the utter amazement of the new proprietor of Fonthill. In many of the works, notes had been made, in the handwriting of Mr. Beckford: the books which contained them were intended to be withdrawn, but, by accident, some escaped discovery; they were discovered by the prying gentlemen of the press, and the memoranda found in several of the books appeared in the newspapers. They were eagerly sought after at the sale, though frequently they presented but quotations from the books: occasionally, however, they expressed opinions, and some of them were of a most singular nature. High prices were given for these, and some, it was understood, were purchased for Mr. Beckford at twenty times the price which the holder had given for them at the sale. His thoughts were often expressed with great force. In one instance, speaking of human nature, he powerfully marked his sense of the humanising power of letters. He pointed to the mind of man as wretched in its native state — as ” blood-raw, till cooked by education.”

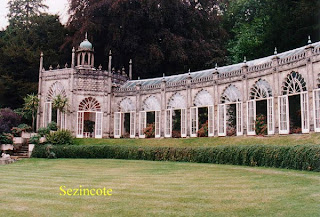

With the money he received from Mr. Farquhar, Beckford purchased annuities and land near Bath. He united two houses in the Royal Crescent by a flying gallery extending over the road, and his dwelling became one vast library. In 1810 Beckford’s second daughter, Susanna Euphemia, married Alexander, Marquis of Douglas, who succeeded his father as 10th Duke of Hamilton, and to her he left all his property. Beckford died at Bath on May 2, 1844, aged 84. Most of Fonthill Abbey collapsed under the weight of its poorly-built tower the night of 21 December 1825.

This link will bring you to the catalogue for the Fonthill Abbey Library of 20,000 books

Also in 1822, on 9 February, Phillips auctioned the contents of Bradenburgh House upon the death of the Queen. Phillips’s royal connections continued, as evidenced by this piece from the Annual Register of 1831 – Sale Of His Late Majesty’s Coronation Robes.— A portion of his late Majesty’s costly and splendid wardrobe destined for public sale, including the magnificent coronation robes and other costumes, was sold by auction, by Mr. Phillips, at his rooms in New Bond Street. There were 120 lots disposed of, out of which we subjoin the principal in the order in which they were put up :— No. 13. An elegant yellow and silver sash of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphie Order, 3/. 8.— 17. A pair of fine kid-trousers, of ample dimensions, and lined with white satin, was sold for 12.v.— 35. The coronation ruff, formed of superb Mechlin-lace, 2/.—50. The costly Highland costume worn by our late Sovereign at Dalkeith Palace, the seat of his Grace the Duke of Buccleugh, in the summer of 1822, was knocked down at 40/.— 52. The sumptuous crimson-velvet coronation mantle, with silver star, embroidered with gold, on appropriate devices, and which cost originally, accordiug to the statement of the auctioneer, upwards of 500/., was knocked down at 47 guineas.—53. A crimson coat to suit with the above, 14/. – 55. A magnificent gold body-dress and trousers, 26 guineas.—67- An extraordinary large white aigrette plume, brought from Paris by the Earl of Fife, in April, 1815, and presented by his lordship to the late King, was sold for 15/.—87. A richly embroidered silver tissue coronation waistcoat and trunk hose, 13/.—95. The splendid purple velvet coronation mantle, sumptuously embroidered with gold, of which it was said to contain 200 ounces. It was knocked down at 55/., although it was stated to have cost his late Majesty 300/.—96. An elegant and costly green velvet mantle, lined with ermine of the finest quality; presented by the Emp

eror Alexander to his late Majesty, which cost upwards of 1,000 guineas, was knocked down at 125/.

Part Two, featuring the Blessington/D’Orsay Auction, coming soon . . . . .

Originally published August 2010