|

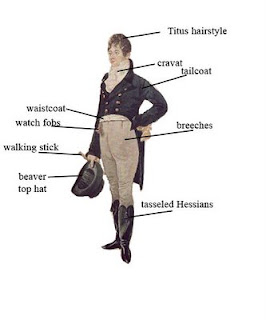

| George, Princeof Wales as Prince Regent, by Sir Thomnas Lawrence, c. 1814 |

This is the first of an occasional series of posts on the English Regency, which began 200 years ago. The Regency has innumerable definitions. In the arts, architecture, society, fashion, decor, and literature, we might date the Regency as being almost the same dates as the long 18th century, from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy to the accession of Victoria in 1837. Others shorten it to the period between the American War (1776)and/or the French Revolution (1789) to the death of George IV in 1830 and/or William IV in 1837. The official Regency lasted nine years, from 1811-1820, when George III died and the Prince Regent became George IV.

|

| Prim Minister William Pitt |

The political world of parliamentary leaders and ministers was alive with rumors and gossip based on long-held political rivalries and ambitions. Richard Brinsley Sheridan, in the absence of Charles James Fox (touring Italy), and other Whigs who enjoyed close friendships with George, Prince of Wales (who would be appointed as regent for his father if the regency bill was passed), were excited. The Whigs could almost taste their return to power. However, the Prime Minister William Pitt, a Tory to the core, saw the matter differently. He willed the King to recover. While stalling for time, a bill setting the conditions and restrictions of the regency was drawn up and debated.

|

| Charles James Fox, Whig leader |

The Prince of Wales, age 26, at first tried to stay publicly aloof from the debates. His life, which we have written about elsewhere and will no doubt write about again, was characterized by considerable conflict with his father. George III was strict with his sons, giving them an excellent education and expecting them to behave with propriety. But like the sons of so many English kings, (see The King’s Speech for a more modern example), Prince George chose to go his own way with regard to lady friends, expensive architectural and collecting projects, and disobedience to his father’s desires.

|

| Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Whig leader |

The Prince considered himself a highly intelligent and principled connoisseur, a clever wit, and The First Gentleman of Europe. Others considered him self-indulgent, a spendthrift, and insensitive. But like so many sons of kings, he had no real job. He wanted to participate in the wars, and envied his brothers: Frederick’s position in the Army and William’s post in the Navy. In 1785, George married Maria Fitzherbert in a ceremony that defied the laws requiring the monarch’ s approval, which couldn’t have been given because she was a Roman Catholic.

|

| Thomas Rowlandson, Filial Piety (Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University) |

iously interested in his ultimate assumption of power. His interest did not escape the notice of the political satirists, such as Thomas Rowlandson. His Filial Piety, above.

|

| Rupert Everett in The Madness of King George, 3rd from left |

By February, the regency bill had passed the House of Commons and was about to be finally debated in the Lords when the King appeared to recover completely. He came back to London and the bill was taken off the Lords’ agenda. A service of Thanksgiving for the King’s Recovery was held at St. Paul’s Cathedral in April of 1789.

These are the events chronicled in the play and film The Madness of King George (1994). Above is a still from the film showing the Prince of Wales as played by Rupert Everett waiting to hear the results of a parliamentary vote. The film is quite accurate in portraying the first regency crisis and the king’s recovery.

|

| A flattering (slimming) portrait of the Prince, c. 1782 |

We will investigate the next chapter in this drama soon.