|

| Walmer Castle, Kent |

From The History of Walmer and Walmer Castle By Charles Robert Stebbing Elvin (1894)

The quiet unostentations life which the Duke of Wellington led at Walmer, has been familiarized to us by Earl Stanhope in his “Conversations.” But one trait must be briefly alluded to, namely, the Duke’s love for children, which was evinced in a characteristic manner. We are told by Lord Stanhope that, in the autumn of 1837, Wellington had staying with him at Walmer Castle, two little children of Lord and Lady Robert Grosvenor, a boy and girl, and these chicks having expressed a desire to receive letters through the post—it was before the days of the penny post—the Duke used to write to them every morning a letter containing good advice for the day, which was regularly delivered when the post came in. He used also constantly to play fooball with the little boy upon the ramparts.

It was in the October of this year that poor Haydon spent some days at the castle, having come down at the Duke’s request, to paint his portrait for certain gentlemen at Liverpool. Haydon relates in his Diary, how charmed he was with the Duke’s playfulness with “six dear healthy noisy children,” no less than with his unostentatious reverence at the parish church on Sunday. . . . . It is further related of the Duke of Wellington, that he sometimes took out with him, in his walks, a number of sovereigns and half-sovereigns, each suspended from a red or blue ribbon, and that when he came upon a group of children, he would present them with one of these, either red or blue, according as they declared themselves when interrogated, to be for the army or navy. The Duke’s early habits are well known, and an old gentlemen still living, tells me that when he was a boy at Walmer, he and his school-fellows used frequently in the summer, to be taken down to the sea near Walmer Castle, at six o’clock in the morning, to bathe, and the Duke would often come on the beach and converse with them.

In addition to children, the Duke also entertained more mature guests at the Castle –

The Duke of Wellington was repeatedly honoured with visits from Royalty, during his occupancy of Walmer Castle. Thus Earl Stanhope mentions in his Conversations his meeting Prince George of Cambridge (the present Duke) at dinner at Walmer Castle, on October 14th, 1833; and on October 17th, 1837, records a luncheon at the Castle to meet the Princess Augusta of Saxony.

From the same source, also, we learn that two years later the Duke of Cambridge (father of Prince George above-mentioned), and first Duke of Cambridge with the Duchess and Princess Augusta, spent five days at Walmer Castle, namely, from October 3rd to October 8th. And how they were entertained we are also informed. On the evening after their arrival, there was a dinner party of eighteen persons, followed by a concert, for which the Duke of Wellington had engaged several vocalists from London, and to which he invited most of the neighbours: another dinner given on the 6th Oct., was followed by a larger party still, and a concert in the evening: while on the last day of their sojourn, October 7th, a great public breakfast given by the Duke in their honour, at 2 p.m., was attended by from a hundred to a hundred and twenty persons, many of whom came from Ramsgate and Dover; and in the evening there was another concert and large party.

But the chief interest centres in the visits of our present beloved Queen, who first became acquainted with Walmer in 1835 ; in the autumn of which year, she being then the Princess Victoria and a girl of sixteen, paid a visit to the Duke of Wellington and lunched at the castle, with her mother, the Duchess of Kent, and the King and Queen of the Belgians.

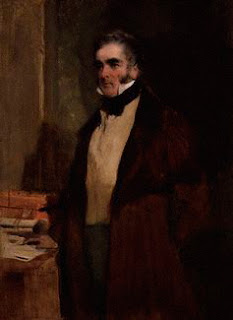

|

| Leopold, King of the Belgians |

The following account of this visit has been preserved in a letter by the then Lady Burghersh to her husband :—” The King and Queen of the Belgians arrived exactly at 2 in the same carriage with the Dnchess of Kent and Princess Victoria. The Duke of Wellington and I went to meet them on the drawbridge, and brought them up the outside staircase to the ramparts (where nearly all the company were already assembled), the lower battery firing a salute. The scene was beautiful; the whole of the beach in front of the castle and the roads leading to Deal and to the village, were filled with people; all the colours hoisted at the different places along the coast and on the ships, of which, fortunately, there were quantities in the Downs. The only drawback was that we were disappointed of getting a band from Canterbury, so there was no music. After walking about the ramparts and speaking with the company, the King and Queen went with the Duke round the garden, but the Princess Victoria had a little cold; so I staid in the drawing room with her and the Duchess of Kent, and baby was brought in and behaved like a little angel, and was much admired. She was sent for again afterwards to see the Queen. As the crowd outside were eager to see Princess Victoria, I asked the Duchess of Kent if she thought she might come out for a moment to shew herself, and I fetched my ermine tippet for her, which she put on, and came out on the ramparts and was very much cheered.”

Seven years later we find her Majesty again at Walmer Castle; being no longer a girl, but a Queen and a mother. It was on the morning of Thursday, November 10th, 1842, that the Royal party, consisting of the Queen, Prince Albert, and th

eir two children, the Prince of Wales and the Princess Royal, left Windsor Castle, accompanied by a distinguished suite, en route for Walmer Castle; where they arrived the same day escorted by a troop of the 7th Hussars, then quartered at Canterbury, and with a guard of honour furnished by the 51st Infantry. With the exception of the journey from Slough to Paddington, the whole distance was accomplished by road; Her Majesty being everywhere greeted with the most enthusiastic demonstrations of loyalty and esteem. On the outskirts of Upper Deal, the Royal Party were met by the Duke of Wellington, who afterwards rode on to receive Her Majesty and the Prince at Walmer Castle, which was then placed entirely at their disposal; the Duke proceeding to Dover to take up his quarters during the royal visit.

Although the accommodation at the castle was somewhat restricted, being much less in those days than at present, no effort was spared to ensure the comfort of the royal guests and their suite. Two of the principal rooms in the castle had been thrown into one, for the sleeping apartment of Her Majesty and the Prince; while the portion of the fortress appropriated for the royal nursery, consisted of four rooms in “the outworks or north tower,” with the windows facing in a northerly direction. Viscount Sydney, as the Lord in Waiting, and Lady Portman as the Lady in Waiting, as well as the Honble. C. A. Murray, Master of the Household, and others, occupied some other rooms; while the rest of the guests were accommodated in a large house about three quarters of a mile away.

The inhabitants of the whole district seem to have vied with each other in their efforts to do honour to the royal visitors; the illuminations throughout the neighbourhood being most brilliant. And on the following morning, when the royal standard was hoisted on Walmer Castle, the Thunderer manned yards, and saluted Her Majesty with twenty-one guns. The royal party remained at the castle nearly a month; and it was while here that the Queen received by special messenger from Downing Street, the news of the recapture of Ghuznee and Cabul, and the rescue of the prisoners.

An incident took place during this visit, which displays, in a remarkable degree, the natural goodness of heart and kindliness of disposition, which have always been shewn by her Majesty in her intercourse with her people. The Queen and Prince Consort were one day walking on the shore in the direction of Kingsdown, when they were driven by a sudden shower to take refuge in an old boat-house, which, besides being a place for storing boat’s gear, served also as a dwelling for an aged boatman—Thomas Erridge—and his wife; who, although they failed to recognize their visitors, readily offered them such mean accommodation as the place afforded. The royal pair were soon provided with a seat, consisting of some spars placed upon empty water-casks and covered with a spare sail; and there they sat and conversed with their simple-minded hosts, until the shower ceased ; and the latter were afterwards rewarded for their rude, but kindly hospitality, with a pension, with which the Queen provided them for the rest of their days.

The last meeting between Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington, took place at Walmer Castle, on a similar occasion to the last, and only two years later. It was on August 17th, 1852, a month before the Duke’s death: the royal squadron having anchored in the Downs for one night, with the Queen and the Prince Consort en route for Belgium, His Royal Highness landed in a small boat from the Victoria and Albert, and paid a visit to the castle, where he had a long conversation with the aged warrior and statesman.

Whilst the Duke took excellent care of his many guests, he seems to have been rather more lenient in his care of the Castle gardens –

The next considerable improvement to the (Castle) grounds was made by the Earl of Liverpool (Warden before Wellington), who added the two meadows— since thrown into one—with the express proviso that, in the event of the office of Lord Warden being ever abolished, they should revert to the representatives of his own family.

The Duke of Wellington did not improve the grounds: on the contrary, he seems to have allowed them to fall into a state that would very much shock the professional gardener. But then the Duke’s gardener was not a professional, but a veteran sergeant of the Peninsular Army, and a Waterloo man, named Townsend, who received his appointment to the post of gardener at Walmer Castle under the following peculiar circumstances. The story goes, that shortly after the Duke became Lord Warden, he received a letter from Sergeant Townsend, complaining that he had been discharged from the service without a pension: that thereupon he immediately replied, “Field Marshall the Duke of Wellington would be happy to see Sergeant Townsend at Apsley House -on Friday at noon “: that on the interview taking place, his Grace inquired, “Do you know anything about gardening?” and, on receiving a negative reply, added, “Then learn, learn, and come here this day fortnight at the same hour.” The sergeant withdrew, and when, in obedience to orders, he appeared the second time at Apsley House, was greeted with—”Take the place of gardener at Walmer Castle; and on replying, “But I know nothing about gardening,” was cut short by the Duke with “Nor do I, nor do I, take your place at once.”

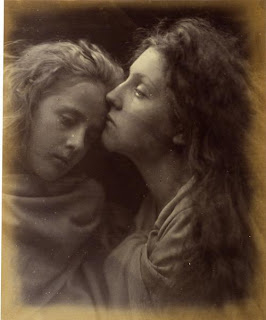

|

HM Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother was Lord Warden for 24 years

and spent many summers in residence at Walmer Castle. |