Mrs M.A.Clarke, as drawn & engraved by C.Williams, published Feb 25, 1809

by S.W.Fores, 50 Piccadilly

In the above print, titled “Committee of Inquiry” (available for £180 @Grosvenor Prints in Hampton, Middlesex), the descriptive text from Grosvenor Prints has Mrs. Clarke “standing in the lobby of the House of Commons, a section of which is seen through the partly open door: the corner of three tiers of empty benches and the gallery, with a strip of the Speaker’s chair, showing his right elbow.” Mrs. Clarke wears a blue pelisse over a simple white dress; on her head rests a straw bonnet with a lace veil. With her left hand she raises the hat’s veil from her face. The very, very large object on her right hand is a fur muff. Again, as per the description, “She is elegant, alluring, and assured.”

But where was Mary Anne Clarke during the period of the trial and through 1813, when, under the terms of her annuity from the Duke of York, she had to leave England for the Continent?

In her questioning at the 1809 trial she stated that she was a widow living in “Loughton Lodge, in the county of Essex.” So, apparently – or, according to her – her husband, Joseph Clarke, the philandering drunkard, is deceased. But was she actually living where she said she was? The truth and Mary Anne Clarke were never friends, so some skepticism is in order.

According to an article by one Richard Morris in the March/April 2008 newsletter of the Loughton Historical Society, there are some doubts as to her residence in the area at all, though Morris, covering his bases, does write at the end of his piece:

“I am, however, convinced that there must be some truth in the story, if only because of Daphne du Maurier’s relationship to Mary Anne Clarke, her reputation as a novelist, the research she did for her book, and the many references in it to Loughton and Loughton Lodge.”

Bless the man, to have such faith in an author’s research! But we know from what Du Maurier said in the preface to her novel Mary Anne that she relied on someone’s “notes” and on the library research of two others. Dicey. So, here’s the dubious part:

“There are in total nine references to Loughton in [the] novel, and one refers to Mary Anne Clarke looking out of the window at Loughton Lodge: ‘at the neat box-garden, the gravel drive, the trim smug Essex landscape’. This can only considered as author’s licence as Loughton Lodge stands on top of Woodbury Hill with its front facing what is now Steeds Way…in 1809 [it] would have given clear views over the Roding Valley and beyond, and the rear which overlooks an attractive part of the Forest.”

The reference in the last line is to Epping Forest, a considerable parcel of wooded area. Hard to overlook.

Morris goes on to say that he can find no specific evidence of Mary Anne Clarke’s time in Loughton, even though a local street – in acknowledgement of her supposed time in the town — was changed from Mutton Row to York Hill in 1850. When Mary Anne was supposedly in residence at Loughton Lodge, though, it belonged to a family named Shiers. True, she could have been a lodger at the Lodge, but lodging in someone else’s digs was never Mary Anne’s style.

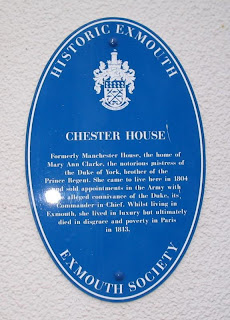

And what of this Loughton Lodge today? Turned into an old folks’ home after World War II, it was subsequently divided into two separate houses. I have not been able to find an image of it, either as it was then, or as it is today. Nor was I able to verify that “a blue plaque” was affixed to the building in April of 2009.

In 1811, wherever Mary Anne was, she did one other thing for posterity, that is, she commissioned the Irish-born sculptor Lawrence Gahagan to sculpt a marble bust of her (now in London’s National Portrait Gallery). It’s very beautiful.

Mary Anne Clarke rises from the open petals of a sunflower. She’s thought to represent Clytie, the abandoned lover of the sun god, Helios, changed into a sunflower so that she could follow her perfidious lover’s progress across the sky each day

So, we come to the question… Do all old English courtesans die impoverished – and disgraced — in France? Grace Dalrymple Elliott died there, in the village of Meudon, and, if not in poverty, close to it; Dorothy Jordan definitely died in awful poverty in Saint-Cloud; Mary Robinson didn’t die in France – she died at home, in England — but she died as poor as it was possible to be; likewise Emma Hamilton, who met her sad demise in Calais.

And then there’s Mary Anne Clarke. Yes, she died in France – after extensive travels through Italy and Belgium — in Boulogne-sur-Mer, but decidedly not in poverty. That generous annuity from the Duke of York saw her through, as it did her daughter Ellen Clarke Busson du Maurier, who raised her family on it.

The irony – there’s always the irony – is that poor Ellen Clarke (said to be as unattractive as her mother was beautiful, with sallow skin and sharp features) apparently was under the illusion for years that she was the by-blow of the Duke of York, but though she was probably not the daughter of her mother’s husband Joseph Clarke, neither could she have been the daughter of Frederick. Her mother – though she certainly knew many men intimately between Clarke and Frederick – did not meet the Duke of York until Ellen was at least six years old. Her biological father is a mystery.

Ellen, so unlike her mother in every way – save perhaps for the sharpness of her tongue — married the inventor Louis-Mathurin Busson du Maurier, a charming, talented dreamer (said to have a beautiful singing voice) who never amounted to anything and was prone, as were others in his family, to depression. His so-called inventions were laughable and he was forever in debt. Although it appeared to have been a love-match, it was disastrous. Ellen had to borrow from her mother and her sister-in-law Louise all her married life. When she came into the annuity in 1852 – either in whole or in part — upon the death of Mary Anne Clarke, she still found it difficult to make ends meet, as her children seemed to have a hard time making decent livings.

George Du Maurier, author of Trilby

Late in his life, however, her eldest child, and her favorite, George Du Maurier, became a successful cartoonist for Punch and other political publications of the day, and, at age sixty, he wrote a bestselling novel, Trilby, inspired by his experiences as an art student in Paris. His son, Gerald Du Maurier, the well-known actor-manager, was the father of Daphne Du Maurier. (There is a marked resemblance in the image above between George and Daphne. Look at their noses.)

Gerald Du Maurier, respected actor-manager and father of Daphne Du Maurier, by Augustus John

Quite a legacy, this of the Busson du Mauriers and the Clarkes. It was a spirited one, for sure, thanks largely to Mary Anne. Daphne Du Maurier, whose attitude towards her ancestor I find somewhat ambivalent, summed up this legacy in The Du Mauriers:

“The pleasant, sweet-natured, melancholy Bussons of Sarthe had not such fortitude. These fighting qualities were bequeathed…by a woman, a woman without morals, without honour, without virtue, a woman who had known exactly what she wanted at fifteen years of age, and, gutter-born and gutter-bred, treading on sensibility and courtesy with her exquisite feet, had achieved it laughing – her thumb to her nose.”

As for the blog post by Kristine comparing Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, to Mary Anne Clarke? Mary Anne could have taught her a thing or two, methinks. Yes, Mary Anne was as greedy as they come, but she was a whole lot smarter and a good deal more conniving. The greed and love of luxury ultimately brought her down – as, indeed, it appears to have brought down this 21st century Duchess – but, while Mary Anne was down, dear readers, she was never really out. The spunky baggage was a survivor, as so many of her courtesan sisters were not. A dreadful woman, but one has to admire her survival skills. I think that, in the end, her great-great-grand-daughter surely did.

Her last words to her son and daughter-in-law were said to be, “It is high time we had another party.”

The novelist Daphne Du Maurier as a young woman

The End

Originally published on October 28, 2010