Originally published in 2010

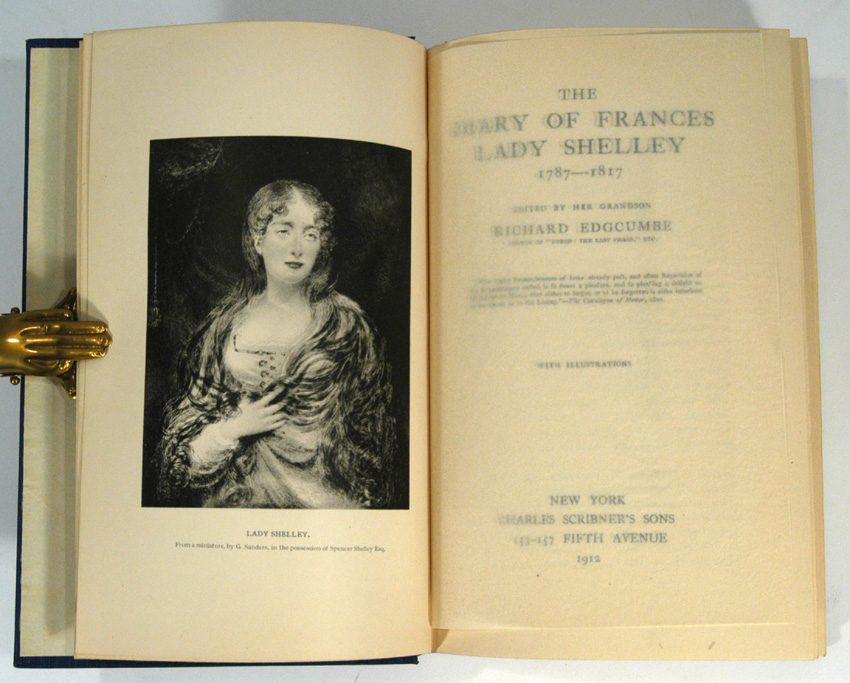

There were two Lady Jerseys during the Regency, Frances, Lady Jersey and her daughter-in-law, Sarah, Lady Jersey, who became one of the Lady Patronesses at Almack’s Assembly Rooms. The elder, and more infamous, Lady Jersey was Frances Twysden, the posthumously born daughter of Rev.Philip Twysden, Bishop of Raphoe (1746–1752) who was allegedly shot while attempting to rob a stagecoach in London(!), and his second wife Frances Carter, daughter of Thomas Carter of Robertstown, Master of the Rolls. Her disreputable father was the third son of Sir William Twysden, 5th Bart of Roydon Hall, by his wife and distant cousin Jane Twisden.

When Frances was seventeen, she married George Villiers, 4th Earl of Jersey, son and heir of William Villiers, 3rd Earl of Jersey and his wife, Lady Anne Egerton. Frances’s husband was nearly twenty years older than she and was Master of Horse to the Prince of Wales and a Lord of the Bedchamber. The reason for the marriage of Lord Jersey to the daughter of a disreputable Irish bishop has not been explained in contemporary accounts. However, her husband’s position within the Royal household soon placed Lady Jersey in close proximity to the Prince of Wales and led to Lady Jersey being well placed for undertaking future mischief.

George IV began his affair with Frances, Lady Jersey, in 1782, although she would also become romantically involved with various members of the English aristocracy. It was not until 1794 that Lady Jersey managed to lure the Prince of Wales away from his illegal wife, Maria Fitzherbert, although he would continue to be romantically involved with Maria until 1811. Having helped to encourage the Prince of Wales to marry his first cousin, Caroline of Brunswick, Lady Jersey nevertheless set out to make Caroline’s life difficult, perpetrating what vies to be the greatest piece of cheek in Regency history, Lady Jersey had herself appointed as Lady-in-Waiting to Princess Caroline. Losing no time in stirring the pot, Lady Jersey met Princess Caroline when she landed at Greenwich on April 5th, 1795 – arrivng late. She then proceeded to usurp the Princess’s rightful place in the Royal carriage by plead motion sickness whenever she rode backwards, thus forcing the Princess to give up her seat in the place of honour.

However Caroline, the potential Queen Consort, saw through the intrigues of her husband’s mistress and, there being no love lost between Caroline and the Prince of Wales, soon cared very little about the matter. In fact, after the birth of their child together, Caroline lived abroad for most of her 25 year marriage to him, taking other lovers, and therefore leaving a void Frances could fill. Because Lady Jersey enjoyed the favour of Queen Charlotte, even the displeasure of George III was not enough to threaten Lady Jersey’s position, and she continued to run the prince’s life and household for some time.

It might be said that Lady Jersey’s reputation for intrigue and malice led to her downfall. The following contemporary letters offer further insight into her personality.

On July 6, 1803, diarist Joseph Farrington wrote: “Lady Jersey is now quite out of favour with the Prince of Wales. She told Hoppner that she met the Prince upon the stairs at the Opera House, & in such a situation as to render it necessary to make room for him to pass which not instantly noticing him she did not do as she wished, which caused Her after He had passed to say a few words of apology. He went forward, and the next day Col. McMahon called upon her to signify to Her `that it was the desire of the Prince that she would not speak to him.’ She spoke bitterly of McMahon for having submitted to carry such a message. She says there is a popish combination against her. (McMahon was Private Secretary and Keeper of the Privy Purse to the Prince of Wales, as well as being a Privy Councilor. He was created a Baronet on August 7, 1817).

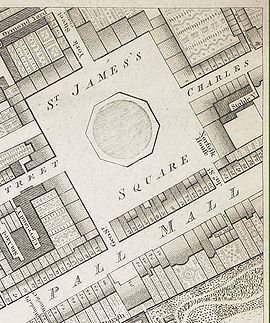

Frances, Lady Jersey, died on July 23, 1821, in Cheltenham. Her daughter-in-law, Sarah, Lady Jersey, was much more beloved by society. Sarah, Lady Jersey, the Lady Patroness who introduced the Quadrille to Almack’s Assembly Rooms and who is Zenobia in Disraeli’s Endymion, was the daughter of John Fane, the 10th Earl of Westmorland, who had scandalously eloped with her mother, the heiress Sarah Ann Child, a member of the Child’s banking family. Born Lady Sarah Sophia Fane, the younger Lady Jersey married George Villiers, the 5th Earl of Jersey, then Viscount Villiers, on 23 May 1804. He succeeded to the title in 1805 and until her death in 1867, Lady Jersey, who lived in Berkeley Square, was the undisputed Queen of London Society, being called, in fact, “Queen Sarah,” although she styled herself as Sally.

Sir William Fraser described her thusly in later life, “Lady Jersey was never a beauty. She had a grand figure to the last; never became the least corpulent, and, to use a common term, there was obviously no “make up” about her. A considerable mass of grey hair; dressed, not as a young woman, but as a middle-aged one. Entirely in this, as in other things, without affectation, her appearance was always pleasant. No trace of rouge nor dye could ever be seen about her. She seemed to take her sovereignty as a matter of course; to be neither vain of it, nor, indeed, to think much about it. Very quick and intelligent, with the strongest sense of humour that I have ever seen in a woman; taking the keenest delight in a good joke, and having, I should say, great physical enjoyment of life.”

After her parents had eloped, Lady Sarah’s grandfather, Robert Child, sought to confound the newlyweds by preventing any of his fortune from going directly to his daughter or the Westmorland family, which he disliked intensely. He made a will leaving the whole of it to any daughter that might be born to the couple. Sarah became an heiress upon his death, inheriting not only his banking fortune, but Osterley Park as well.

On July 6th, 1825, Mrs. Arbuthnot wrote the following complaint about Lady Jersey: “I was very cross at the King’s ball, I was so provoked with Lady Jersey. In the first place, she was chaperone to Miss Ponsonby, who is just come out & very shy & who she left entirely to herself & took no notice of, while she went about flirting with every man she could get hold of. Miss Ponsonby came & staid with me & protested she would never go to a ball again with Lady Jersey.

Perhaps one of Lady Jersey’s most constant adversaries was Princess Lieven, who wrote of one of their many skirmishes on August 23, 1823: “I see that you like Lady Georgina Wellesley (Lady Cowley, sister-in-law to the Duke of Wellington); I can imagine that you would. She has plenty of good sense. We have never been very intimate but we were always good friends. She is said to like gossip. I have never found out if she deserves the reputation. I am so far from having that fault, and generally I am so quickly bored with trivialities, that it s rare for anyone who is endowed with a little tact not to realize immediately that this is the kind of conversation I like least. So she might well be a gossip without my knowing it. She has given you a garbled and abridged version of the mischievous stories Lady Jersey tired to spread about me; and Lady Jersey has the most dangerous tongue I know. I will not bore you, and myself, with the whole truth; but I cannot leave you under a false impression. Here is what happened in the end. She wanted to have it out. There was no way of escaping. She talked and wept for an hour on end. The sound of her voice and her vulgar way of talking upset me so much that I felt almost sea-sick; incidentally, I was quite incapable of understanding what she was trying to say. So, to be done with it, I said: “Tell me, in a word, if you have come to make peace. If so, I am ready; if you have come to declare war, I accept the challenge.” That brought on a fit of hysterics and frightful reproaches for my coldness. “Is it possible to say such freezing things to one’s friend?” In the end, I really believe I drove her out, for I was beside myself. So here we are friends or enemies, just as she likes; for, once again, it doesn’t matter to me, so long as I am left in peace.”

Perhaps one of Lady Jersey’s most constant adversaries was Princess Lieven, who wrote of one of their many skirmishes on August 23, 1823: “I see that you like Lady Georgina Wellesley (Lady Cowley, sister-in-law to the Duke of Wellington); I can imagine that you would. She has plenty of good sense. We have never been very intimate but we were always good friends. She is said to like gossip. I have never found out if she deserves the reputation. I am so far from having that fault, and generally I am so quickly bored with trivialities, that it s rare for anyone who is endowed with a little tact not to realize immediately that this is the kind of conversation I like least. So she might well be a gossip without my knowing it. She has given you a garbled and abridged version of the mischievous stories Lady Jersey tired to spread about me; and Lady Jersey has the most dangerous tongue I know. I will not bore you, and myself, with the whole truth; but I cannot leave you under a false impression. Here is what happened in the end. She wanted to have it out. There was no way of escaping. She talked and wept for an hour on end. The sound of her voice and her vulgar way of talking upset me so much that I felt almost sea-sick; incidentally, I was quite incapable of understanding what she was trying to say. So, to be done with it, I said: “Tell me, in a word, if you have come to make peace. If so, I am ready; if you have come to declare war, I accept the challenge.” That brought on a fit of hysterics and frightful reproaches for my coldness. “Is it possible to say such freezing things to one’s friend?” In the end, I really believe I drove her out, for I was beside myself. So here we are friends or enemies, just as she likes; for, once again, it doesn’t matter to me, so long as I am left in peace.”

Perhaps Lady Jersey’s greatest misstep was to draw the displeasure of the Duke of Wellington. On March 9th, 1832, Lady Holland wrote to her son: “You know that he (the Duke of Wellington) never goes near Ly Jersey, a complete alienation.” And again on August 2nd, 1845, Lady Holland writes to him: “Yesterday the Beauforts gave a dinner to the King of Holland, quite one of form and etiquette. The D. of Wellington was to take out according to precedence, Ly G. Coddington as a Duke’s daughter. Lady Jersey bustled up, shoved her off, and said to the Duke, “Which will you take?” He very gravely and properly kept to his destined lady, without answering Lady Jersey. They say she is really too impudent and pushing.”

A prime example of the manner in which the Duke of Wellington dealt with those with whom he had no patience is demonstrated by the following anecdote I found on the Villiers family website,

The Jersey Cup . On one occasion, the Duke had been invited to Lady Jersey’s home at 28 Berkeley Square and arrived to find the ante-room littered with gifts. Realizing that he’d forgotten the occasion of the party and had brought nothing with him for his hostess, the Duke picked up a China Vase as he made his way through the reception rooms and presented it to his hostess with due solemnity. “Oh, how delightful” said Sarah, “the Duchess of So-and-So gave me one just like it. I must go and put them together and make a pair.”