The Duke of York set Mary Anne up in lavish accommodations in a mini-palace at 18 Gloucester Place, and by 1805, as his official mistress, she was entertaining, as one source put it, “sumptuously”. She was said to have had twenty servants, which included a housekeeper, five/six maids, two butlers, six or more other male servants (probably footmen and coachmen), and three/four chefs. She had two coaches and at least ten horses. There was also “an elegant mansion at Weybridge” for her sole use.

‘The York-minuet’ (Frederica Charlotte Ulrica Catherina, Duchess of York; Frederick, Duke of York and Albany) by James Gillray (1791)

The prince was married. He was the first of King George II’s children to get married. He’d wed his cousin, Princess Frederica of Prussia, a woman noted for her extremely tiny feet, in 1791. Frederica was petite, very short, not at all attractive, and said to have bad teeth. The duke was no prize himself, described as “a giant of a man…with [a] great bluff red face…bulging eyes…ponderous belly [and a] prominent nose.” Even more detailed is this from another source: “a red, blotched face…a great paunch…a purple, bulbous nose”.

Though Frederica, known as Freddie, was lively, praised for her “neatness”, and considered to be a sensible woman, the couple did not mesh and the marriage was not a success. They lived apart, she at Oatlands Park in Surrey, with eighteen dogs; she had many friends, among them the famous Beau Brummell. (Romance novelist Rosemary Stevens, a few years back, played with Freddie and the Beau’s relationship in a series of mysteries with Brummell as a kind of Regency Sherlock Holmes. Check them out, they’re fun to read!)

At Gloucester Place, Mary Anne Clarke was said to have eaten off exquisite china plates that once belonged to the family of the Duc de Bern, and to drink from crystal wine glasses that had cost upwards of “two guineas a-piece.” (A guinea is a pound plus a shilling.) How much did all this cost to maintain? Mary Anne was never one to stay within a budget, as her past so well illustrates. Her talent – or one of them, at any rate – lay in extravagance.

According to Mary Anne, she received from £1,000 to £1,200 annually from the Duke of York, in monthly allotments, for the maintenance of this enormous household. (Bear in mind that, at that time, one pound was worth seventy to eighty times what it is worth today.) This is at odds with the statement of the Chancellor of the Exchequer at the 1809 trial that she was actually paid £6,000 yearly. Mary Anne countered that her payments from the Duke were irregularly doled out. (It is interesting to note here that the royal brothers received many complaints from their ladybirds over the years that payments were not always forthcoming; this has been documented by the experiences of Mary Robinson and Grace Dalrymple Elliott, among others.)

So, to supplement her income, the avaricious, luxury-loving Mary Anne Clarke hit upon a scheme. She would take the lists of army men up for promotions that were sent to her lover and add the names of soldiers who would pay her for the surreptitious promotions. Only a few each time, added at the very end of the lists to which she was privy, thanks to Frederick — who carelessly kept them lying around — so as not to arouse suspicion. But she got much too greedy…and she was caught. By 1809, the jig was up.

The Bishop And His Clarke Or A Peep Into Paradise… The Duke of York, Commander-in-Chief of the army (and titular Bishop of Osnabruck, as per this reference) being solicited by Mary Anne Clarke to obtain promotions for her paying clients and friends. The caricature is by Rowlandson, printed by Tegg, 1809.

In January 1809, a little-known Welsh MP, Colonel Gwyllym Lloyd Wardle, alleged in the House of Commons that Frederick, as Duke of York — the “spare” after his brother the heir to the throne — and Commander-in-Chief of the Army, “had sanctioned, facilitated, and personally profited from the illicit trafficking in army commissions that his former mistress, Mary Anne Clarke, had engaged in while under his ‘protection’.” (The Duke of York Affair, Philip Harling, The Historical Journal, 39, 4 (1996), page 963.)

Captain Gronow, in his gossipy memoirs, states that Wardle got wind of Mary Anne’s dealings owing to becoming “intimately acquainted with her… [and was] so great a personal favourite that …he wormed out all her secret history, of which he availed himself to obtain a fleeting popularity.” Interesting, but, as with anything Gronow says, one has to have the salt shaker handy.

The modern Circe or a sequel to the petticoat”, caricature of Mary Anne Clarke by Isaac Cruikshank, 15 March 1809. Her lover Frederick, Duke of York resigned from his post at the head of the British Army ten days after the caricature’s publication.

Nevertheless, the charge was sensational, leading to not one but three trials from 1809 to 1813. The first one was the major trial; the subsequent ones were libel suits brought against Mary Anne Clarke and some pamphleteers. Eight specific – and serious — cases of selling commissions were brought out in the 1809 trial, and are examined minutely in the AAIM, for those who want the sordid (and fascinating) details, but, briefly, it came down to Mary Anne Clarke letting it be known that she would use her influence over the duke to secure commissions and preferments, whether deserved by the petitioners or not, and if this was done with the full knowledge and/or encouragement of the Duke of York. The prices for her intervention into this Army business ranged from £2,600 for promotion to Major to £400 for a mere Ensign. (In the drawing above of the Bishop and his Clarke, the army lists are shown pinned to the almost-conjugal bed shared by Frederick and Mary Anne.) The caricaturists had a field day!

As noted in the caption above, Prince Frederick was forced to resign as Commander-in-Chief of the Army owing to the scandal, but he was reinstated shortly after he was found to be innocent of all the charges brought against him. Another widely circulated caricature was this, attributed to C. Williams and showing Mary Anne with the infamous promotion list in her hand standing before the “York Commission Warehouse”:

Colored etching, published 1809, shortly after Colonel Wardle had exposed the army commissions scandal in the House of Commons, this satire shows Mrs Clarke with a price list for the sale of commissions. On the right is her intermediary, Domenico Corri, a music master; above him hangs upside down the Duke of York’s portrait. Mary Anne is saying that she has bargains for sale but they have to be taken advantage of now because her partnership is dissolving!

The manner in which Mary Anne carried on at the trial was said to have been a tour de force worthy of any seasoned stage performance; her quick wit parried and thrust all questions sent her way and impressed spectators. But her reputation – such as it was – was forever ruined. The Duke of York was able to come back; she wasn’t. It was not a good thing to be identified from thence forward as a friend of Mary Anne Clarke’s; she became a pariah, shunned by the society she in which she’d once played such a large part.

Gillray got into the act, too:

Pandora Opening Her Box, colored aquatint by James Gillray, published by Hannah Humphrey, 1809

After the trial, undaunted, Mary Anne let it be known that she intended to publish Frederick’s love letters. Like his brother George in the case of his mistress Mary Robinson, Frederick had been indiscreet. The boys made too many negative remarks about their family members, the royal family. Sir Herbert Taylor was engaged to enter into negotiations with Mary Anne’s lawyers for the purchase of the letters and the destruction of all other papers still in her hands.

Mary Anne received an enormous annuity – on top of an immediate £7,000 cash settlement — her son George’s schooling and subsequent Army commission was paid for, and the annuity would pass on to Ellen Clarke, Mary Anne’s daughter, at her death. (Similar to the arrangement with Mary Robinson and the Prince of Wales, but Mary and her daughter got nothing in comparison with the monies paid out to Mary Anne Clarke.)

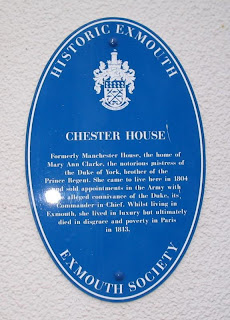

The terms of the annuity also insisted that Mary Anne quit England and reside on the Continent. She was not to publish anything about the royal family, nor was she to say anything that could be deemed disrespectful about them. Though, much later, she once attempted to break the terms of the arrangement, having been approached by a publisher who promised her many thousands of pounds, her lawyers persuaded her to keep the fat bird in her hand rather than seek ephemeral birds in the bush.

The MP who made the initial allegations against the Duke of York, Colonel Wardle, did bring suit against Mary Anne and two pamphleteers for libel – her name was attached to one of the pamphlets – but they were all acquitted. In 1813, however, Mary Anne again went too far and was once again sued, this time for libel of a powerful politician; she was unable to talk her way out of the predicament – the evidence was too strong against her – and she was convicted, spending nine months in prison, supposedly in solitary confinement.

Part Four Coming Soon!

Originally published on October 26, 2010