Now for a closer look at this National Portrait Gallery retrospective… There are some surprising portraits here, not the least the paintings of the Waterloo generals, Wellington, et al., and an amazing capture on canvas of the saintly William Wilberforce, the great anti-slavery crusader. But although it is the beautiful, sensually painted women who draw the eye, it is the eye-stopping portrait of a young man who may hold a clue to the centuries-old puzzle of Thomas Lawrence’s sexuality.

In her review of the National Portrait Gallery exhibit in The Observer (October 24th, 2010), Laura Cumming asks the viewer to “consider Lord Mountstuart of Bute in Spanish costume, his manhood barely concealed in skin-tight trousers. Silhouetted against a stormy sunset in his Byronic black cloak (Lawrence arguably pioneered the look, Byron was only seven at this time), Mountstuart treads upon the toy landscape below. His body is wildly elongated, his face more or less Hispanicised and yet all these implausibilities are somehow swept aside by the sensuous conviction of the paint.”

That depiction of the young lord’s “manhood” caused quite a stir at the time. Lawrence thrusts Mountstuart’s thrusting hips and bulging thighs, encased in skin-tight trousers, right into the viewer’s face. It’s not subtle, not by any means, and this reproduction hardly does it justice, for seeing it up close and personal is an entirely different experience, one that stops the viewer dead in his tracks, and my feeling is that it is intentional, that Lawrence wanted the viewer’s face rubbed into that young buck’s manhood.

Or was it his own face that he wanted to rub into Mountstuart’s crotch? It’s unsettling. And it’s also revealing that the 1923 Grieg edition of Farington’s diaries censures what Farington said about this portrait in May of 1794. Luckily, the editors of the Yale edition had no such qualms.

Farington wrote in his diary on the 5th of May, 1795, that King George III “started back with disgust” when he saw the portrait on display at the Royal Academy exhibition for that year. From the exhibition catalog (edited by A. Cassandra Albinson, Peter Funnell and Lucy Peltz), a comment and quote from an early 19th century book of anecdotes has more to say on this painting: The unbridled sexuality of this portrait, led another critic to sarcasm: ‘We wish he had been a Bishop, as then his Cassoc [sic] might hide those eccentricities…at which delicacy must blush, and modesty turn aside.”

The editors kindly enlarge that part of the portrait — “those eccentricities” in question — for the further edification of the reader on page 124 of the catalogue. Pretty blatant, this, and, to me, it’s significant that Lawrence was never so blatant in his painting of dashing young trousered men again.

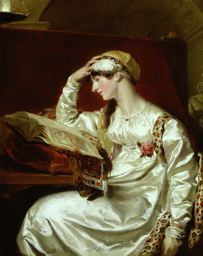

In Lawrence’s later years one woman in particular appeared to provide him with companionship, Isabella Wolff, who first met him when she sat for her portrait in 1803. Isabella was the daughter of Norton Hutchinson, a prominent East India trader and the estranged wife of Jens Wolff. A merchant, shipbroker, merchant, and collector who served as the Danish Consul, Jens Wolff was of Anglo-Danish heritage.

The couple had separated after 18 years of marriage and had one son, Herman St. John Wolff, who may have been born any time between 1810 and 1814 (or perhaps before those dates). The lack of certainty as to the correct birth date of Herman Wolff has led to speculation that he was the son of Isabella and Thomas Lawrence. Is there anything to back this up? Lawrence did appear to be fond of the boy and went on trips to the continent with him, but is that enough to make a case for paternity? It is also possible that Herman was Wolff’s son by another woman, not his wife Isabella. The jury is still out on this one.

Lawrence and Isabella Wolff knew each other for at least twenty-six years. She’d sat for a portrait in 1803, while she was still married to Jens Wolff, and they’d become close, even intimate, friends. Indeed, the artist John Constable, writing to his wife in 1824, simply stated what was being said at the time in London art circles: “A Mrs. Wolfe came in the evening. She is very pretty; & talks incessantly of all the arts & sciences… She is quite an intimate of Sir Thomas Lawrence, who has often drawn her. Her husband, from whom she is parted, in the Danish consul & in every sense of the world a Wolfe.”

Very odd, that comment, that Jens Wolff is “in every sense of the world a Wolfe,” because there was gossip in a newspaper, the Literary Gazette, very shortly after Lawrence’s death that he had been involved with a “Mrs. W, the wife of a foreign minister, whose brutal treatment [had thrown] her upon the protection of Sir T. Lawrence.” Had Jens Wolff been a wife beater? Was that what Constable was alluding to?

They were definitely close, as evidenced by this letter to her that survives, written from Rome in late June of 1819, when Isabella was about 50 and Lawrence only a couple of years older. He wrote:

My Bed Room Window is so small that only one Person can conveniently look out of it, but it looks over the Pope’s garden and St. Peters, Monte Mario &c., and as sweet Even’g closes I often squeeze you into it tho’ it does hurt you a little by holding your arms so closely within mine.

It reads real. Real and affectionate. This is not the Lawrence so many described as a manipulative social climber, overly charming, out to seduce by the sweetness of his words and the timbre of his voice. Isabella Wolff and Lawrence were definitely close, but how close is still a matter for conjecture. The bulk of their correspondence, unfortunately, was apparently censured both by his first biographer and by Lawrence’s relatives. Richard Holmes, however, dismissed her role in the painter’s life as simply “maternal.”

Contemporaries agree that Isabella Wolff was a great source of inspiration for him; she seemed to serve him as a beloved muse. (As perhaps, Sarah Siddons had, so many years before?) The portrait above was one that Lawrence could not seem to give up. He worked on it for over twelve years. (He also drew her many times.) At the Royal Academy exhibit in 1815, this portrait held pride of place. It was his only painting at that exhibition of a female subject.

The philosopher and critic William Hazlitt called it “a chef d’oeuvre of style…enough to make the Ladies vow that they will never again look at themselves in their glasses, but only in his Canvasses.” The critical reaction at the time to the portrait of Isabella Wolff was uniformly positive.

Mrs. Wolff’s is a classical pose, Grecian inspired, and, indeed, she is shown studying a book open to an image of the Delphic Sibyl. There is something of the Greek priestess in her attitude, with her hand on her head, and critics have suggested that being cast as a sibyl, as one of those priestesses who looked into the future and passed judgments, may fit with the role she played as mentor and muse in Lawrence’s life. It is an eye-catching portrait fraught with feeling.

Isabella Wolff died in 1829; Thomas Lawrence died unexpectedly – he had not been ill — very soon thereafter, in 1830. Whether or not their relationship was sexual in nature – whether they might have had a child together – whether he was heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual — is irrelevant to the obvious closeness of their friendship. I would not hesitate to say she most probably meant a great deal to him and that the shock of her death no doubt hastened his demise. And that, at the end, is what is important, that his life, as it neared its end, at long last, did have what anyone would not hesitate to call love. It was surely about time.

Self-portrait, circa 1825

Self-portrait, circa 1825