On 7 March 1787, Wellesley was gazetted ensign in the 73rd Regiment of Foot. In October, with the assistance of his brother, he was assigned as aide-de-camp, on ten shillings a day (twice his pay as an ensign), to the new Lord Lieutenant of Ireland Lord Buckingham. He was also transferred to the new 76th Regiment forming in Ireland and on Christmas Day, 1787, was promoted to Lieutenant. During his time in Dublin his duties were mainly social; attending balls, entertaining guests and providing advice to Buckingham. While in Ireland, he over extended himself in borrowing due to his occasional gambling, but in his defence stated that “I have often known what it was to be in want of money, but I have never got helplessly into debt.”

Two years later, in June 1789, he transferred to the 12th Light Dragoons, still as a lieutenant and according to his biographer, Richard Holmes, he also dipped a reluctant toe into politics becoming an MP for Trim in the Irish House of Commons and in 1791 he became a Captain and was transferred to the 18th Light Dragoons. During this time, he met and wooed Catherine (Kitty) Pakenham, the daughter of Edward Pakenham, 2nd Baron Longford, who was described as being full of ‘gaiety and charm.’ Wellington offered for her hand in marriage in 1793 and was summarily refused by Kitty’s brother Thomas, Earl of Longford, who saw nothing very much in the young Wellesley to recommend him to the family, as he had a number of debts, poor professional prospects and no sign hung round his neck that read, “Future Duke of Wellington, Incredibly Wealthy, In Charge of Everything.”

Arthur Wellesley, or Wesley, as he then styled himself, then left Dublin for active service in the Netherlands and apparently did not look back on his lost love. Nowhere in his correspondence for the interceding 12 year interval does he make any reference to Catherine Pakenham, or does a letter to or from her exist. Then, we are to believe that Wellesley went to spend his leave at Cheltenham and met a mutual friend, the busybody and yenta Lady Olivia Sparrow, who twitted him with heartlessness to her bosom friend “Kitty Pakenham,” and assured him that his ladylove had never changed.

“What!” Wellesley was purported to exclaim, “does she still remember me ? Do you think I ought to renew my offer? I’m ready to do it.”

Supposedly, he then wrote at once to Miss Pakenham, renewing his proposal of marriage. She replied that, as it was so long since they had met, he had better come over and see her before committing himself, lest he should find her aged and altered. Sir Arthur replied that minds, at all events, did not change with years and hastened over to Ireland. Though, upon again laying eyes on Kitty, he was said to have exclaimed, “She has grown ugly, by Jove!” they were married by Wellesley’s clergyman brother Gerald in Lady Longford’s drawing room in Dublin.

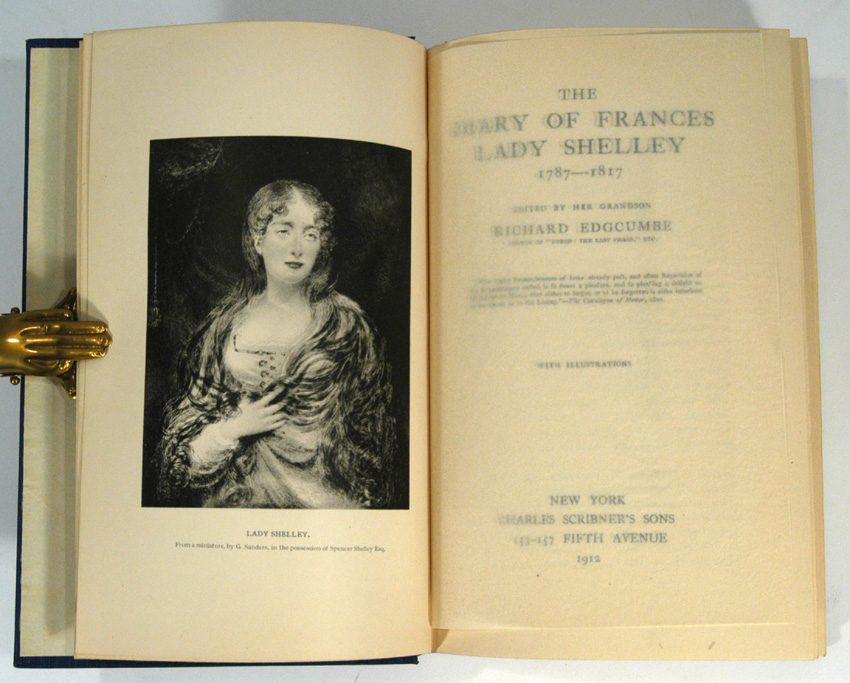

Whilst the Duke possessed many laudable qualities, the ability to be a great husband and father was not amongst them. He treated Kitty rather coldly beginning very early in their marriage. Some say it was because he found out after the fact that Kitty had engaged herself to another suitor prior to Wellington’s return, and had thrown that young man over in favour of Wellington who, by this time, had fair amount of fame, a growing fortune, a title and glittering prospects. Supposedly, Wellington found the fact that Kitty herself did not disclose the engagement to him deceitful. His great good friend Lady Shelley wrote of Wellington at the end of her life, “As he never deviated from the truth himself, he scorned deceit or equivocation in others. Whenever he caught any one out in telling him an untruth, he was extremely harsh and severe.”

However, there is evidence (still being pursued by Kristine and Victoria) that some great bruhaha took place early in their marriage involving something to do with Kitty’s family; something along the lines of her having lent them a goodly amount of money and hiding the fact from Wellington. In fact, Wellington thenafter forbade Kitty’s ever taking their sons to Ireland with her again. She was free to visit her family whenever she wished – the boys were not. Exactly what the fracas was about is still shrouded in mystery, but the fact remains that Wellington was a cold and distant husband to Kitty.

Wellington’s close friends found it difficult to conceive that he’d ever married Kitty, who was naturally shy and further inhibited by the hero worship she felt for her husband. At least one of his intimate friends, Harriet Arbuthnot, questioned him about the odd match, as we read in The Journal of Mrs. Arbuthnot, Volume I –

“He assured me he had repeatedly tried to live in a friendly manner with her . . but that it was impossible, that she did not understand him, that she could not enter with him into consideration of all the important concerns which are continually occupying his mind and that he found he might as well talk to a child . . . . she made his house so dull that nobody wd go to it while, whenever he was in town alone . . . everybody was so fond of his house that he could not keep them out of it . . . .

“. . . I could not at last help saying to him that the more I knew him the more was I unable to recover from my astonishment at his having married such a person . . . He said, “Is it not the most extraordinary thing you ever heard of! Would you have believed that anybody could have been such a d —–d fool?”

Now, Reader, here is the part in which the mystery lies – Mrs. Arbuthnot relates the story of Lady Olivia Sparrow’s interference, of Wellington telling her that at that time he “did not care a pin about any one else or what became of himself” and his going to Ireland and marrying Kitty and then Mrs. A. continues: “I told him that in all my life I had never heard of anybody doing so absurd a thing, that there could be but one justification, his having been desperately in love with someone who had ill-used him and being in a state of desperation at the time, and even for that he was too old. He agreed cordially in my abuse of him and said I could not think him a greater fool than he did himself.”

So . . . . with whom had Wellington been in love? Who had broken his heart? Victoria and Kristine continue to pursue this burning question, as well . . . . It should be noted that the Duchess of Wellington died in the Duke’s London residence, Apsley House, on 24 April 1831. In the days before her death, the Duke was devoted to her needs and never left her side. In the end, he regretted that they were able to achieve a meeting of minds only at the end of her life.