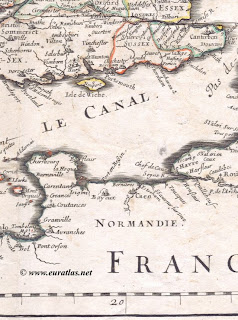

As Victoria and I will soon be crossing the English Channel, I thought it would be appropriate to share with you some of the passages from period letters related to the subject which contain first hand accounts of all the various perils attached to making the crossing, from techy customs agents to foul weather and mal de mer.

In fact, the Crossing on the ferries and packets was often so bad that Lady Mary Wortley Montagu paid five guineas in order to hire a private boat to cross channel, rather than taking the Packet. The following is a passage from a letter to her husband about the journey.

(Calais) July 27 (1739)

I am safely arrived at Calais, and found myself better on ship-board than I have been these six months; not in the least sick, though we had a very high sea, as you may imagine, since we came over in two hours and three-quarters. My servants behaved very well; and Mary not in the least afraid, but said she would be drowned very willingly with my ladyship. They ask me here extravagant prices for chaises, of which there is a great choice, both French and Italian: I have at last bought one for fourteen guineas, of a man whom Mr. Hall recommended to me. My things have been examined and sealed at the custom-house: they took from me a pound of snuff, but did not open my jewel-boxes, which they let pass on my word, being things belonging to my dress. I set out early tomorrow. I am very impatient to hear from you: I could not stay for the post at Dover for fear of losing the tide. I beg you would be so good to order Mr. Kent to pack up my side-saddle, and all the tackling belonging to it, in a box, to be sent with my other things: if (as I hope) I recover my health abroad so much as to ride, I can get none I shall like so well.

From The Berry Papers, Being the Correspondence Hitherto Unpublished of Mary and Agnes Berry

Friday, 16th (April, 1802)

Went on board the ‘Swift;’ sailed from Calais Pier a quarter after eleven: fine day, but the wind fell almost entirely. At seven o’clock in the evening we were within five miles of Dover in a dead calm; got into a Dover boat, were rowed into the harbour, and arrived at the York Hotel at a quarter after eight, having been just nine hours on our passage. (Quelle horror!)

And about a later return passage:

Sunday, 26th (May, 1815)

We arrived at Dover at six o’clock in the evening. Unfortunately, the custom-house officer was in a bad humour; he kept my sac de nuit and dressing-case; and instead of finishing the examination of the trunks, opened them, and threw the contents of one into the other, so as to spoil all within. I complained in vain, and was obliged to borrow night things from the landlady at the inn.

Monday, 27th

The custom-house officer of yesterday evening was still more rude to-day. I think he had been blamed for the manner in which he had treated me, and that made him worse. He kept all my shoes, pieces of worn dresses, and things that were marked, and made me pay for flowers which had been worn, etc. The superior custom-house officer, I well saw, wished to make him behave better, and to return what he had taken, but to no purpose.

The following passages were written by Princess Lieven

Calais, June 3 1822 – I crossed from Dover in two and a half hours, with the most superb weather. Tomorrow, I shall sleep at Lille and, the day after tomorrow, at Brussels.

And

Brighton – January 5, 1823 – I left Paris on the morning of the 3rd, I reached Dover after traveling all night. We had a good crossing; but, as we only embarked at five in the afternoon, it was pitch-dark when we neared the English coast. The packet-boat could not get in, and stayed out at sea. I decided on taking the small boat, much to the disgust of my husband, who does not fancy jaunts of that kind. There was a swell; the night was pitch-black. Getting into the boat was no fun at all; there was no gangway, no rope ladder, nothing; one had to wait for a wave to lift the cockle-shell high enough for one to throw oneself from the deck of the packet-boat into the arms of a waiting sailor. I managed very cleverly. When we got to shore, they had to run the boat aground; that was the worst part, for the waves drove us ashore and then dashed over us, and I was drenched from head to foot. When we reached the inn, the old house-keeper made me drink a glass of brandy and put me to bed; that is the great English remedy, and it did me good.

From the Letters of Lady Louisa Stuart

Versailles, 2nd of Septr. 1834.

I told you I should not write in a hurry, and you will be inclined to say I have kept my word. However here is a large sheet of thin paper, and so now let us see what we can do. We set out on Wednesday, having been, as you know, greatly obliged to your good-humoured sisters for a drive as far as London Bridge the day before. Wednesday was rather rainy, but cleared up towards evening. We slept at Dover, and embarked at seven the following morning; a very calm sea. By following a piece of good advice I had received, sitting still in the carriage, and leaning back with my eyes shut, neither speaking nor moving hand or foot, I escaped giddiness and sickness. Yet Louisa (Bromley), who did the same, was sick, though not usually so, therefore I crowed over her, a triumph I did not expect. The trial was short, for by half past nine we arrived in the road of Calais, but the tide not serving, were forced to go on shore in a boat, and had several hours to wait for the arrival of the carriage, which could not be landed till past three. Then came custom-house and various arrangements, so that the sun was setting before we were fairly off, and we only reached Boulogne, where we found the hotel choke full, and had very bad quarters. That evening three or four pelting thunder-showers compelled us to shut up our landaulet, though it was already very warm; but there ended all reason to complain of the weather (except, indeed, of its extreme heat last week), for from Friday the 12th to the present date it has been uninterrupted sunshine and moonshine, and these last three days we have had some refreshing autumn breezes.

And about her return

There arose a furious gale of wind, which did not abate in the least till Sunday night, so though we reached Calais rather early on Friday, we could not sail before Monday morning, and then had an unpleasant passage in a very rough sea with a contrary wind that made everybody mortally sick. We had seven carriages on board, there were as many in another vessel; in short, Calais was crowded, and all the packets were on that side of the water. We got to land in five hours, at eleven o’clock, but the tide did not serve for our carriage to be disembarked, passed through the custom-house, and repacked, till it was too late to proceed farther. We therefore got up by candle-light a second morning, and as the D

over road is almost all up and down hill, it was near seven on Tuesday evening when we alighted at this door. For all these perils and hardships (mighty great to be sure) I am none the worse, but Louisa caught cold by going to look at the wreck of a poor vessel which was lost off Calais on Saturday, and consequently she is as yet unable to set out for Baginton.

From the Letters of Lady Harcourt

To G. K. S.

Albert Gate, Tuesday, March 10, 1891.

We had an awful storm yesterday, a regular blizzard, and a terrible night in the Channel. One of the good boats, the Victoria, was out all night, not daring to land at either Dover or Calais. One of our young attachés was on board, bringing over despatches, and they say he looked green when he finally did arrive. The trains were snowed up everywhere, even between Folkestone and London, and the passengers nearly frozen and starved. It seems incredible in such a short distance. The young men are generally rather eager to bring over despatches, but I rather think this one won’t try it again, in winter at any rate. I am extraordinarily lucky in my crossings, because probably I am a good sailor. I go backward and forward in all seasons and always have good weather. The Florians have had some wonderful crossings, nine hours between Calais and Dover, both of them tied in their chairs, and the chairs tied to the mast.

And what better way to finish up this or any other piece of writing than with a letter from the Duke of Wellington? Here is a letter written to his niece, Lady Burgeresh, about the plans he’s made for her Channel crossing. Lest you think that Wellington was using his influence to secure special priviliges for his family, it should be known that Priscilla had been in England, quite ill, and was returning in an official capacity to Naples, where her husband was Ambassador.

From the Correspondence of Lady Burgeresh

London, August 6, 1826

Dearest Priscilla,

I am about to leave town, and write you a line to be sent to you to-morrow. Lord FitzRoy (Somerset) will have written you last night that I could not get for you the same vessel which conveyed you to Margate; but the Admiralty have consented to your having the use of another steam vessel, which is used for the purpose of towing, and therefore the accommodation is not quite so good as in that vessel of which you had the use before. Lord FitzRoy is, however, to go to Deptford to see her to-morrow, and if the accommodation should not be sufficient you are to have the use of the Admiralty yacht, a sailing vessel in which the accommodation is excellent, and the above-mentioned steam vessel to tow her, so that your passage is secured to Boulogne or Dieppe as you may think best. I now entreat you not to fix too early a day for your departure, as you cannot detain the vessels at Margate. You must go when they will arrive there. I have now named the 18th. But have said it is possible a later day may be fixed. You had better fix a day on which it will be certain that you can go. Recollect that you was a week too soon the last voyage, and that in this voyage, particularly if you determine to go to Dieppe, you may have some sea. Write to me and direct here. I am going only to Stratfield-Saye, and I will go to you as soon as I shall know whether I am to be Summoned to the Lodge on the King’s birthday, which I understood from the lady that she intended.

God bless you. Remember me most kindly to Emily, and believe me,

Yours most affecy.,

W

Unfortunately, since this post was written, the travel company has made a change to our plans – Kristine and Victoria are now scheduled to take the Eurostar through the tunnel, from London to Brussels. No mal de mer for us, though we know the train has broken down a few times. Instead of a Regency journey lasting days, we should now make it from St. Pancras, London, to Brussels, Belgium in slightly less than three hours. Rats . . . . . we were so looking forward to making the crossing in period fashion!