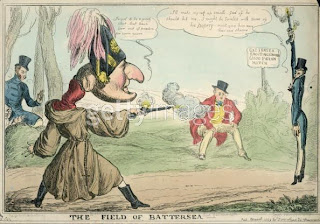

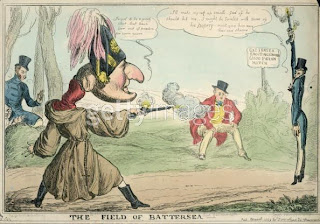

“Gentlemen, are you ready? fire!” The Duke raised his pistol and presented it instantly on the word fire being given; but, as I suppose, observing that Lord Winchilsea did not immediately present at him, he seemed to hesitate for a moment, and then fired without effect.

I think Lord Winchilsea did not present his pistol at the Duke at all, but I cannot be quite positive, as I was wholly intent on observing the Duke, lest anything should happen to him; but when I turned my eyes towards Lord Winchilsea, after the Duke had fired, his arm was still down by his side, from whence he raised it deliberately, and, holding his pistol perpendicularly over his head, he fired it off into the air.

The Duke remained still on his place, but Lord Falmouth and Lord Winchilsea came immediately forward towards Sir Henry Hardinge, and Lord Falmouth, addressing him, said, “Lord Winchilsea, having received the Duke’s fire, is placed under different circumstances from those in which he stood before, and therefore now feels himself at liberty to give the Duke of Wellington the reparation he requires.” He seemed to pause for an answer, and Sir Henry replied, “The Duke expects an ample apology, and a complete and full acknowledgment from Lord Winchilsea of his error in having published the accusation against him which he has done.” To which Lord Falmouth answered, “I mean an apology in the most extensive or in every sense of the word;” and he then took from his pocket a written paper, containing what he called an admission from Lord Winchilsea that he was in the wrong, and which he said was drawn up in the terms of the Duke’s last Memorandum.

Upon reading it, it appeared that the word apology was in no place inserted, although the paper expressed that Lord Winchilsea did not hesitate to declare of his own accord that he regretted having unadvisedly published an opinion which had given offence to the Duke of Wellington, and offered to cause this expression of regret to be published in the ‘Standard’ newspaper, as the same channel through which his former letter had been given to the public.

The Duke, who had come nearer, and was listening attentively, said in a low voice, “This won’t do; it is no apology.” On which Sir Henry took the paper to the Duke, and walked two or three paces on one side with him, but immediately came back, saying, ” I cannot accept of this paper unless the word apology be inserted.” He then took a paper from his pocket, and was proceeding]to read, saying, “This is what we expect;” when Lord Falmouth, interrupting him, said, ” I assure you what I have written was meant as an apology;” and he entered into a discussion, asserting that the admissions contained in his paper were the same as those, or were quoted from those, in the Duke of Wellington’s own Memorandum. Sir Henry said, “My Lord Falmouth, it is needless to prolong this discussion. Unless the word apology be inserted, we must resume our ground.” And, turning to Lord Winchilsea, whom Lord Falmouth had taken aside to converse with, he said, “My Lord Winchilsea, this is an affair between the seconds;” on which Lord Winchilsea retired.

After some little hesitation, Lord Falmouth said he did not well see how he could put the paper into any other form; and, referring to me, he said, half aside, “Do you not think it sufficient?” I said, “Yes, if you insert apology in the body of your paper.” To which he replied, “Well, Sir Henry, I will do it in this way, and I trust that will answer every purpose. I will insert apology here in this manner “—writing with his pencil after the words ” hesitate to declare of my own accord that (in apology) I regret,” etc. Sir Henry then went to the Duke and spoke a few words, but came back almost instantly, and said to Lord Falmouth he was satisfied, or that the paper would do.

He then added, “And now, gentlemen, without making any invidious reflections, I cannot help remarking that—whether wisely or unwisely, the world will judge—you have been the cause of bringing this man (pointing to the Duke) into the field, where, during the whole course of a long military life, he never was before on an occasion of this nature.” The Duke came forward, bowing coldly to Lord Falmouth and Lord Winchilsea, the former of whom seemed greatly affected, and stated he had always thought and told Lord Winchilsea that he was completely in the wrong; on which Sir Henry remarked that, if he did so, and came with the writer of the letter to the ground, his Lordship had done that which he (Sir Henry) would not do for the dearest friend he had in the world. Lord Falmouth then addressed himself to the Duke in vindication of his conduct, and was beginning to express the pain and anxiety he had experienced during the whole of these proceedings; but the Duke interrupted him, lifting up his hands and saying, “My Lord Falmouth, I have nothing to do with these matters.” He then touched the brim of his hat with two fingers, saying, “Good morning, my Lord Winchilsea; good morning, my Lord Falmouth,” and mounted his horse, and Sir Henry having also got on horseback and said, “I wish you good morning, my Lords,” they both rode quickly off the field.

I took up the pistols, gave them to the Duke’s groom to put into the carriage, and was walking away, when Lord Falmouth called to me to say that Sir Henry Hardinge had not verified the paper, and requested me to do so; which I did by putting my initials under the word apology, which was interlined, and signing my name at the top and bottom. Lord Falmouth repeated again and again how painful it had been to his feelings to be engaged in a business of this kind with a person for whom all the world, and he and Lord Winchilsea in particular, had so much respect and esteem as the Duke of Wellington; and on my remarking, “Then, why did you push it so far?” he replied, “It was impossible to avoid it. The fact is, Lord Winchilsea had been very wrong; so much so that he could not have made any apology sufficiently adequate to the offence consistently with his character as a man of honour without first receiving the Duke’s fire. Had he done what he did in the heat of debate, or in the excitement of the moment, he might have easily retracted his expressions; but he had sat down deliberately and written and published a letter in the ‘Standard,’ containing accusations and insinuations which were highly improper. He certainly had discovered soon after that he had no right to attribute to the Duke’s conduct the motives he had done; but this only rendered an ordinary apology the more inadequate; and he had, therefore, determined first to give the Duke satisfaction, that his expression of regret might have more effect.” I said I could not agree with him in the view he took of the matter. That what might be justifiable, or even praiseworthy, towards an ordinary a

dversary, was very different towards a man like the Duke of Wellington; “for, indeed, my Lords,” said I, “I never even contemplated the possibility of his being engaged in an affair of this kind, and I am filled with something approaching to horror, when, after exposing himself for so many years in fighting the battles of his country, after triumphing over all her enemies by a series of victories the most glorious and complete that ever adorned the page of history, I see he may still be forced to put himself on a level with other men, and expose to impertinence that life which he has so often risked for the benefit of us all.” Lord Falmouth said, “On this occasion, at least, he did not risk his life. I assure you most solemnly, Sir, that on no other condition would I have accompanied Lord Winchilsea except on that of his acting in the manner he has done, and his declaring to me upon his honour that he would not return the Duke’s fire.” I said, “Indeed, gentlemen, I was never so agreeably relieved from the most painful suspense and anxiety I ever experienced as when I saw Lord Winchilsea fire his pistol in the air. I had before felt towards you both something like what I could suppose myself capable of feeling towards parricides; but I immediately saw that, although I might consider you wrong, you had erred perhaps through an excess of mistaken generosity; or, at all events, this is the construction you must desire to be put upon your conduct. Yet still I cannot help regretting you should have considered all this necessary, and forgotten the circumstances of your antagonist. But it is all owing to that cursed spirit of party, which now, as in all times, obscures the judgment and destroys the better sympathies of your hearts.” Lord Winchilsea then replied, as if speaking to himself, “God forbid that I should ever lift my hand against him!” We had by this time reached the carriage, where, bowing, I took my leave, and drove directly home.

Having related these circumstances as minutely as my recollection enables me, I must now be permitted to mention the impression the distinguished actors in this affair made upon my mind throughout the whole of it.

In meetings of this nature the principals are supposed to commit themselves entirely to the guidance of the seconds, and thus become in their hands almost passive agents. On this occasion the Duke conformed himself strictly to this rule; and I could not help admiring how meekly and submissively he conducted himself through the whole of this affair.

To those who, unacquainted with the Duke, have only looked at his greatness, and recollect him at the head of his army, driving his enemies before him in all the triumph of victory from the Tagus to the Garonne in one tide of uninterrupted success, or who, after he had vanquished his great rival on the plain of Waterloo, and arrived at one bound under the walls of Paris, have beheld him in that capital in all the splendour of conquest, surrounded by emperors and kings, himself the most distinguished of all the members of that brilliant assemblage, fixing the boundaries of kingdoms, and controlling by his single word the destinies of the world, this may appear scarcely credible. To others who know the Duke well, it will excite neither wonder nor astonishment, for, whilst he is perfectly confident in himself, and well aware of the respect due to his great actions, no man assumes less. With the most perfect knowledge of human nature, he has always set a just value on popular applause, and has never for a moment allowed himself to be blinded by fortune, or intoxicated with praise. In his honest pride there is no arrogance, in his dignity no haughtiness, in his superiority no vainglorious display; but simple, plain, and natural in his manner, he is, without exception, the most unaffected of men. In all situations and on all important occasions he presents the same person. Calm, modest, unassuming, yet dignified, resolute, and firm, easy, unembarrassed; never losing for a moment his self-possession, never impatient or hurried.

Sir Henry Hardinge, the straightforward, frank, honest, warm-hearted soldier, full of zeal for his old Commander, full of indignation at seeing him obliged to seek reparation of this kind for an unprovoked and unmerited insult, but never allowing either to carry him to any improper warmth; clear, distinct, acute, decided, he went through the whole of this affair—to him most painful—with a degree of judgment, temper, discretion, and good feeling, which quite charmed me.

From Sir Henry’s hint I kept as near the opposite parties as I well could without being remarked, and I have much pleasure in bearing testimony to the gentlemanlike behaviour of Lord Winchilsea. His manner throughout was exceedingly becoming; no haste, no forwardness, no presuming. His demeanour was gentle, calm, and unobtrusive. His countenance, which is pleasing, wore a certain expression of pensiveness, and, as I thought, of regret, as if dissatisfied with himself; and as he seemed to have put himself entirely into the hands of his friend, I confess I felt, in spite of me, a degree of interest and concern for him. He showed no levity, no indifference, but steady and fearless he received the Duke’s fire, without making the slightest movement or betraying any emotion, except that when he raised his arm and discharged his pistol in the air, I thought he smiled, as if to say, “Now, you see, I am not quite so bad as you thought me.”

I was sorry for Lord Falmouth, who was much affected, and seemed to feel deeply all the responsibility of the task he had to perform.

J. R. Hume.