The following letter, published under the heading It Is Lucky That Christmas Does Come But Once A Year, first appeared in an 1853 volume of Punch.

DEAR PUNCH.-I live in lodgings. I am one of those poor unfortunate helpless beings, called Bachelors, who are dependent for their wants and comforts upon the services of others. If I want the mustard, I have to ring half-a-dozen times for it; if I am waiting for my shaving water, I have to wander up and down the room for at least a quarter of an hour, with a soaped chin, before it makes its appearance.

But this system of delay, this extreme backwardness in attending to one’s simplest calls, is invariably shown a thousand times more backward about Christmas time. I am afraid to tell you what I have endured this

Christmas. My persecutions have been such as to almost make me wish that Christmas were blotted out of the Calendar altogether.

I have never been called in the morning at the proper time. My breakfast has always been served an hour later than usual—and as for dinner, it has been with difficulty that I have been able to procure any at all!

This invasion of one’s habits and comforts is most heart-rending; and the only excuse I have been able to receive to my repeated remonstrances has been, ‘Oh, Sir, you must really make some allowances; pray recollect, it is Christmas time.’

Last week I invited some friends to spend the evening with me—but I could give them neither tea, nor hot grog, nor supper, nor anything—because, ‘ Please, Sir, the servant has gone to the Pantomime—she’s always allowed to go at Christinas time.’

Hang this Christmas time! My canary died this morning. Upon inquiry I found that it had not had any seed or water for three days, Every one was so busy at. this time of the year. It was lucky, I thought, that I had some more expressive means of making my wants known than my poor starved canary, or else I should have shared its unhappy fate a week ago.

A day or two before Christmas Day my dress boots burst, and I sent them to be mended, with a pressing request that they might be sent home immediately. Well, Sir, from that day to this, I have never seen my dress boots. The only explanation I get to my frequent inquiries is, “Very sorry, Sir, but it is impossible, Sir, to get the men to work at this time of the year.” It has been the same with a dress coat, which was split down the back. The tailor informs me, with a face as long as his pattern-book and containing nearly as many colours, that ‘he regrets it extremely—but every one of his workmen have been drunk since Christmas Day – they always do at this period of the year.’

What has been the consequence, Sir? Why I have only one pair of dress-boots, one dress-coat. I am not ashamed to confess I cannot afford more. And the consequence has been, that I have not been able to accept many pleasant Christmas invitations, because I had not the proper attire to go in to them! Instead of amusing myself and others elsewhere, I have been obliged to mope at home over a sickly fire, expiring by inches for the want of a few nourishing coals, and without even a drop of hot water to make myself a comforting glass of grog. Servants, it would seem, have a time-honoured privilege to go out and do just as they please at Christmas time!

I suffered cold, incipient rheumatism, and violent tooth-ache, for three sleepless nights, because there was a broken window in my bedroom. I stamped, I swore, I rung the bell like a madman, but not a person could I get to put in a fresh pane for me. No: ‘It was Christmas time, and the men wouldn’t work, to please anybody.’

The worst yet remains. As I was out walking, a coalheaver knocked against me. He then abused me, and because I complained rather warmly, he bonnetted me, and ultimately knocked me down. I have still the marks of his brutality on both my eyes. Yet, Sir, will you believe it, this savage met me the following morning in Court; his wife was with him, and she said, half-crying, ‘Her husband was very sorry, and so was she; but the fact was, he had taken a little drop too much, but she hoped I would excuse it—it was Christmas time.’ Pretty compensation this to a man who has received a couple of black eyes !

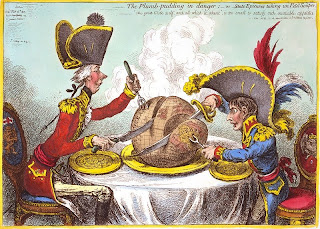

Now, Sir. it seems to me, from the above grievances, (and I have not enumerated one half of them), that Christmas is, with a certain class of people, a privileged period of the year to commit all sorts of excesses, to evade their usual duties, and to jump altogether out of their customary avocations into others the very opposite of them. For myself, I am extremely glad that Christmas does come but once a-year. I know I shall go, next December, to Constantinople, or Jerusalem, or the Minories, or some place where the savage customs I have described do not exist; for I would not endure another Christmas in England for any amount of holly, plum-pudding, or Christmas-boxes in the world.

I have the misfortune to remain, Mr. Punch,

Your much-persecuted Servant,

An Old Bachelor.